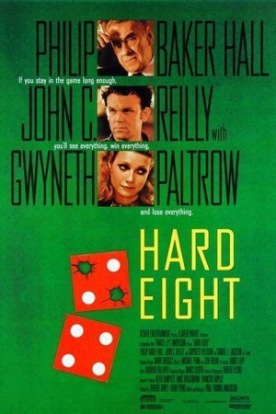

Hard Eight

Hard Eight is a brilliant little film by Paul Thomas Anderson, who also wrote the screenplay. It is a retelling (sort of) of Shakespeare’s Tempest set in the seedy but ever-atmospheric world of Nevada gambling dens. It begins with a castaway called John (John C. Reilly), washed up outside “Jack’s Coffee Shop” somewhere along a highway outside Las Vegas. John is sitting on the ground with his knees pulled up to his chest and looking lost and forlorn. An older and relatively well-dressed stranger, who later introduces himself as Sydney (Philip Baker Hall), offers to buy him a cup of coffee. John explains that he has no money—though he claims not to have lost it gambling—and he needs $6000 to bury his mother. Sydney says he’s not going to win $6000, but offers him a ride to Vegas and a $50 stake.

John is naturally suspicious and warns Sydney that he knows three kinds of karate: ju jitsu, Akido and regular karate. But he is also not a real bright guy. He finally agrees to Sydney’s proposal on three conditions: “a, you give me a ride to Vegas; two, you give me $50 and c, I sit in the back. Soon, however, he comes to trust Sydney, who shows him how to get a free room for the night by seeming to gamble $2000 with no more than $150. John is impressed with Sydney’s savoir faire, but is still worried about how he is going to bury his mother. Sydney says he knows a guy in L.A. who might help.

Then we cut away and are told it is two years later. John has “worked it out” about his mother’s funeral and is now attached to Sydney as a permanent protégé. They appear to be living in nearby hotel rooms, and John is devoted to Sydney, even to the point of dressing like him. It is less clear what it is that Sydney is getting out of the relationship. Two new characters are now introduced: Jimmy (Samuel L. Jackson), a security man at a local (Reno) casino and an obvious hustler, to whom Sydney takes a dislike, and Clementine (Gwyneth Paltrow), a cocktail waitress and part time prostitute whom he appears to like. Sydney is similarly protective toward her, and she is, like John, rather a dim bulb. It seems a match made in heaven, but it is Sydney who pushes the two young people together.

When he comes in with coffee and finds John and Clementine playing checkers on the bed and laughing it is an echo of the scene in The Tempest where Prospero sees Miranda and Ferdinand playing chess. We are also beginning to see Sydney as a kind of magician, who shows John how to live off the gambling industry and to get free TV in his hotel room. And in this little paradise, Jimmy is the Caliban. He makes fun of Sydney. Though he once saw him make a really “ballsy” bet—the sort of thing that is still talked about among his set—now he seems to have got old and timid, the kind of guy who sits around in a bar and plays keno for two dollars a time. Sydney, for his part, both hates and fears Jimmy—mostly because he threatens to lead the innocents, John and Clementine, astray. But we soon find that he has another, more personal, reason to fear him.

One evening, we see Sydney observing at a craps table. A young man throwing the dice, who looks and acts as if he is a boor even when he isn’t drunk, calls him “old timer” and invites him to bet, taunting him from time to time. At last, he makes another one of his “ballsy” and unpredictable bets: $2000 on the “hard eight” (i.e. double four). Even the jerk is impressed. But it’s an “easy eight” (five/three) that comes up. Sydney loses. He walks away with a philosophic shrug. But it is a reminder of his former potency which we carry with us as we wonder if the old magician can work one last trick to ensure the happiness of the young ones.

For later that night he is lying on his bed with all his clothes and the lights on—as if he were waiting up and fell asleep—when the phone rings. It is John and Clementine. They need him right away. Without any further questions, Sydney goes to find them. The next scene presents one of the best and funniest—and at the same time most poignant bits of movie making I have seen for a long time. It is a lovely, beautifully written and acted and perfectly observed passage about which I can give almost nothing away without spoiling your enjoyment of the film. Suffice it to say that, in the end, there is the same sort of bittersweet quality to it that you find in The Tempest. And if it has not quite the play’s profundity, it is still a splendid picture that cries out for a bigger audience than it is ever likely to find.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.