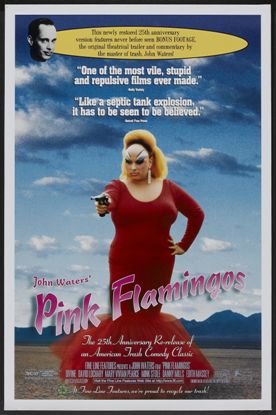

Pink Flamingos

Pink Flamingos by John Waters (1972), now re-released, is not a film which it is really possible to review. It contains sex scenes, both homo and heterosexual, weird perversions, bestiality, coprophagy, incest, madness, murder, torture, mutilation, rape, kidnapping, cannibalism, and the sale of human babies — and to all of this it invites and (in my case at least) receives our assent in the form of laughter. It is also an interesting social document for a number of reasons, not least because it is a kind of volt-meter to measure the potential for shock, both in the early 70s and now.

Sexual perversions with chickens, for instance, are pretty much a constant I would guess, though Waters manages to make this one of the funniest scenes in the movie. But baby-selling in 1972, designed to supply babies to lesbians, seems to have been thought of as in a class with pornography shops and heroin pushing at elementary schools. Now that lesbians are on prime-time TV, such a practice aspires to middle-class respectability. But doesn’t this sort of miss the point about lesbianism, or, indeed, any homosexuality? Isn’t the whole idea of it bound up with its being a perversion? If it is not forbidden passion, what’s the point of it? Instead of forbidden, now, it is fawned over and admired, and anyone who doesn’t think it quite as respectable as Mom and Pop’s old-fashioned double bed suddenly finds himself classed among the bigots.

I wonder if homosexuals look at a film like Pink Flamingos with a certain nostalgia, a longing for the old days when, instead of trying to marry each other, they saw themselves as entering into a Faustian pact with the devil and breathing a Satanic defiance of their own to the tyrant of the universe. Who needs just another legitimate expression of one’s sexuality? There is something of that kind of savage joy in John Waters’s Mephistophelean countenance when he appears at the end to show us his favorite out-takes.

A similar feeling seems to energize his actors, especially the marvelous Divine, who has no desire to be the sort of lovable drag-queen that Hollywood has so recently and so uneasily clasped to its bosom. Instead she pursues quite without remorse or liberal-minded tolerance her campaign of vengeance against the Marbles (the almost equally wonderful Mink Stole and David Lochary), her rivals for the title of “filthiest person alive”

“Nobody sends you a turd, momma, and expects to live,” says Divine’s beloved son, Crackers (Danny Mills). And, sure enough, she captures the Marbles and summons the tabloid media to witness their execution.

“Do you believe in God?” a reporter asks Divine.

“I am God,” says Divine.

Fascinating to think that, as recently as 1972, that too must have seemed shocking.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.