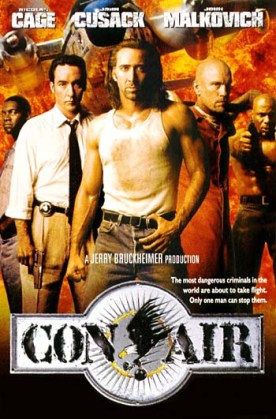

Con Air

Judging from one or two other reviews I have seen, critics seem to think that Con Air, directed by Simon West and produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, is meant to be a witty send up of the macho action flick of which it is ostensibly an example. Maybe this is because Mr West has a background making TV commercials in England and is therefore assumed to be hip and postmodern and not just a glorified pyrotechnical expert. But if the picture was intended to poke fun at its own assumptions, it does not do so very successfully.

It is true that there are one or two examples its nearly two hours of a sense of irony and fun underlying the movie—as for example when one of the super-baddies with the typically lurid moniker “Cyrus the Virus” (John Malkovich) meets his only rival in super-badness, one Garland Greene (Steve Buscemi). The latter is so bad that he is trussed up in a fashion obviously meant to recall Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. His 30 odd victims were so ghoulishly mutilated and killed that another of the super-baddies whispers in awed tones that he “makes the Manson family look like the Partridge family.” So when he comes on board this converted military air transport, called “The Jailbird,” Cyrus is asked what the other superbaddies are going to do with him: “I don’t know, but this is no way to treat a national treasure. Let him out.” Then he whispers to him: “Love your work!”

Not exactly sidesplitting, I agree, but evidence, at least, that there is a postmodern sense of irony and parody at work here. As is Greene’s turning out, when unbound, to be a Lecter-like philosopher, quoting Dostoyevsky and observing of another of the superbaddies that “he’s a fount of misplaced rage” for whom “moments of levity are painful.” Unfortunately, such indications are far too few and are massively outweighed by a plethora of explosive special effects which suggest a fatal unfamiliarity with the virtues of economy of effect and understatement. Of course this may itself be a species of irony. You go way over the top in explosions just as you go way over the top in badness. But it is hard to put across an ironic explosion, and as you sit in the audience the film’s absurdly protracted ending looks designed to appeal not to sophisticates but to the usual crowd of 12 year old TV burnouts.

Also, Nicholas Cage, whatever his virtues as an actor, simply cannot do the hero—an ex-Army Ranger jailed for killing a redneck thug who had attempted to molest his pregnant wife—with his tongue in his cheek. His excess of goodness is meant as counterpoint to the others’ excess of badness and is symbolized by the little stuffed rabbit he is bringing home for his daughter’s birthday when he is finally paroled. Thus he is given what is meant to be a funny line when he kills one of the superbaddies who had taunted him with the stuffed rabbit and refused to put it back in his box of possessions. Addressing the s.b.’s dead body he says: “Why couldn’t you put the bunny back in the box?”

It’s just not a funny line, not coming from Cage. In fact his best line comes when he is being tender and encouraging to the black fellow-parolee (Mykelti Williamson, who played a similar sidekick role in Forrest Gump). It is loyalty to this man, who is ill with diabetes and needs a shot of insulin, which keeps Cage on the flight with the superbaddies when they take over the plane, in spite of his little girl waiting at home. The reluctant hero pretends to be one of the bad convicts, while setting up a line of communication with John Cusack’s Federal marshal, Vince Larkin. But, marvelling to his diabetic friend how they have got into this situation, he says: “Somehow they managed to get every creepin’ freak in the universe on this plane and then somehow they managed to let them get control of the plane and somehow we got right in the middle of it.”

We know how it feels.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.