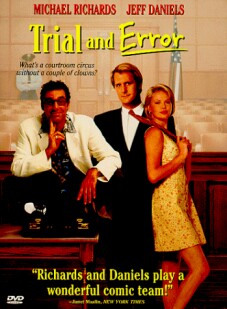

Trial and Error

Trial and Error by Jonathan Lynn, to a screenplay by Sara Bernstein and Gregory Bernstein, based on the former’s short story, has its funny moments, though the clichés come too thick and fast for the film to be quite satisfying in the end. In fact the basic situation the comedy presents us with is one of the hoariest of Hollywood clichés: that of the up-tight Yalie WASP, Charlie Tuttle (Jeff Daniels) who, teamed with a manic, vaguely ethnic actor called Richard Rietti (Michael Richards), finally learns what a ridiculous character in John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy calls “the art of living.” Given this almost fatally familiar formula, it is amazing that the film succeeds as well as it does.

Partly this success is owing to the skill of Mr Richards, a fine comic actor whose deadpan delivery is perfect even while suggesting that he is on the verge of hysteria. His audition for a part, by which we are introduced to him as an actor, consists of him alone on the stage miming being beaten to a pulp by a couple of mafia thugs. It is hilariously funny. He is also the kind of guy who thinks it might be a good pick-up line to a girl in a bar (Jessica Steen) to say: “Sometimes, I think intercourse is over-rated; I’m a hugger myself.”

The story concerns Rietti’s attempt to stage a bachelor party for Tuttle, even though the latter has to go to a sleepy little town in Nevada for his future father-in-law’s high-powered L.A. law firm, of which he has just been made a partner. Tuttle, acting the nerdy lawyer in the bar gets himself beaten up and can’t appear in court next day. Never mind, all he has to do is ask for a continuance. Rietti goes in his place. But the judge (Austin Pendleton) says no to the continuance and the trial must go forward — with Rietti pretending to be Tuttle for the duration. The judge denies the motion at the insistence of the tough-as-nails prosecutor, Elizabeth Gardner, who turns out to be the woman in the bar that Rietti had attempted to pick up the night before.

The case is that of a con-man called Benny Gibbs (Rip Torn) who had swindled a lot of people by offering to sell them, for $17.99, “a copper engraving of the Great Emancipator” — by which he means a Lincoln-head penny. “He doesn’t appear to have the highest level of innocence,” Tuttle explains to his future father-in-law over the phone. “No, I understand that. Neither do the rest of our clients.”

The basis of the comedy is in the notion that Rietti as Tuttle throws himself into the role of defense attorney. He even devises his own version of the Twinkie defense, insisting that Gibbs has endured “years of torment in snack food hell” even though an increasingly irate Tuttle insists that “no one gets a sugar high and commits mail fraud.” Rietti forges ahead anyway and even finds his own expert witness, a new-age nutritionist (Dale Dye), to explain to the bewildered jury that “give or take a nitrogen” the chemical formula for cocaine and for refined sugar are nearly the same. As his pièce de résistance he has Gibbs himself take the stand and tell a ridiculously lachrymose story of his early life in an orphanage (from which he was unjustly thrown out) which is what formed his unbreakable addiction to sweets.

All this is very funny, but the humor is undercut by the overly familiar lessons being given to Tuttle by a sexy waitress called Billie (Charlize Theron) in how not to be WASPy and uptight. What’s the betting that Charlie will eventually learn not only to loosen up but that the earthy Billie will win him away from his rich-bitch fiancée, Tiffany (Alexandra Wentworth), back in L.A.? And to make things even more maudlin, we have the developing romance between Rietti and the prosecutor, in spite of the fact that she learns he has committed several felonies by pretending to be an officer of the court. She, like Billie, is a way too-obvious symbol of freedom, streaking over the desert on her motorcycle with her hair (under a fetching helmet) streaming behind her in the wind. Such stuff is a reminder of the cliché at the heart of the whole film — something we otherwise might have forgotten. For just a moment we are encouraged to think of the implications of presenting the actor as lawyer and the lawyer as actor, but the moment soon passes.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.