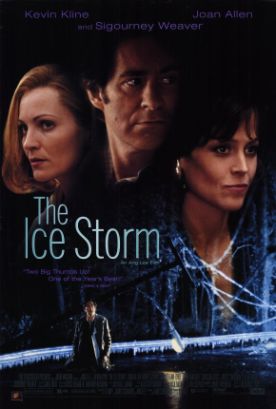

Ice Storm, The

The Ice Storm, directed by Ang Lee from a screenplay by James Schamus, based on a novel by Rick Moody, is a very moving film which, nevertheless, ultimately undermines its own emotional force by trying, after the manner of so many recent movies, to be as much an historical as a literary statement.

For what, exactly, is the point of setting the film in 1973? In one way, the answer is obvious. America has just left Vietnam to its unhappy fate; Nixon is on the television, sweatingly mendacious about his Watergate ill-doings; the sexual revolution of the sixties has reached the suburbs, and paunchy advertising executives are dressing like kids and swapping wives; middle-class kids are smoking dope and parroting radical and countercultural slogans. It is a very precise moment of social and moral breakdown which is certainly worth any serious historian’s careful scrutiny.

But Ang Lee, the director of such fine films as The Wedding Banquet, Eat, Drink, Man, Woman, and Sense and Sensibility, falls into the trap, which has caught so many recent filmmakers, of seeing this moment of historical significance as an opportunity to try to re-create the period feel of 1973. The reason I call this a trap is that the movies are so good at these re-creations that they completely take them over. We have seen many recent evocations of the 1950s, for example, such as Going all the Way and The Locusts just in the last month, which have spent large portions of their overstuffed budgets on getting just the right cars, the right clothes, the right TV, music and accessories down to the smallest details—and then using them to set off laughably inadequate dramas.

Now we are seeing the same thing being done for the 1970s, not only by Ang Lee but also by Paul Thomas Anderson in Boogie Nights. (It would be an interesting question, probably requiring a dissertation in its own right, why we seem to be skipping the decade from about 1964 to about 1973.) And boy does Ang Lee, more even than Anderson, get the seventies right! Right down to those fat leather watchbands and the old fashioned ice-cube trays and Kevin Kline’s amazingly variegated collection of loud vests. Sure enough, there’s Nixon on the TV, along with “Divorce Court” and “Batman” , and people talking about Deep Throat and their fashionable therapies while listening to cheesy synthesizer music and consuming astonishing quantities of booze and cigarettes. This is familiar territory.

And that’s the problem. It’s too familiar. We have been here before and left it behind. Just listen to the 1990s audiences react to those old-fashioned hair-dos and peasant dresses and bell-bottom trousers. And the waterbed! It’s priceless. What a laugh. We are meant to laugh. But it is a cheap laugh, and what the laughter in fact accomplishes is to put a barrier between the audience and the characters. We are being invited to patronize them, which makes the process of identifying ourselves with them—the sine qua non of true artistic experience—almost impossible. This is a fatal mistake, for it allows us to wriggle out of the range of that accusatory finger that all the greatest works of stage and screen point at us. Tu quoque!

The Ice Storm tries to create that self-identification with one hand while undermining it with the other—by allowing us to feel knowing and superior vis à vis its wounded characters. And this state of mind invites us to patronize them morally as well, to tell them, in effect, that they should have known better and in fact would have known better if only they were as wise as we are. They were prisoners of their time. Unlike us, who imagine ourselves to be richer, wiser, more sophisticated, the poor slobs were caught up in the consciousness of their times—which times are continually insisted on as being of crucial relevance.

All this having been said, I find it amazing that the film is as successful as it is. The dénouement really is heartrending—though perhaps more so to conservatives and those believe that these characters are not mere leftovers from a bygone decade but the first of the postmodern men—that in fact they are just like us in being inheritors of the social, moral and intellectual devastation of the 1960s. Part of its success too is owing to the excellent performances in leading roles of Kevin Kline, Joan Allen, Sigourney Weaver and some terrifically good child actors: Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, Elijah Wood and Adam Hann-Byrd.

One feels slightly the weakness of the film’s plotlessness and the many narrative loose ends. Together with its emphasis on sexual secrets, these things help to create that air of soap opera which is the enemy of all things serious. The continuing saga of the Hoods and the Carvers only comes to its point by means of what seems an artificial device—a terrible accident.Yet it is also true to say that the tragicomedy of suburban American life in the 1970s is lent its peculiar emotional resonance by the same soap opera elements, as contrasted to the seriousness with which these people have suddenly learned to take themselves. It all contributes to the film’s final, harrowing outpouring of emotion and the surprising success, in spite of its shortcomings, of the portrait of spiritual devastation.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.