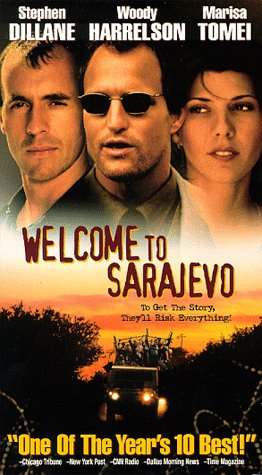

Welcome to Sarajevo

Welcome to Sarajevo, directed by Michael Winterbottom and written by Frank Cottrell Boyce, is based on the true story told in the book Natasha’s Story by the British television journalist Michael Nicholson. The movie fictionalizes it, calling the journalist Henderson (Stephen Dillane) and the little Bosnian girl he rescues from the carnage of 1992-3 and later adopts Emira (Emira Nusevic). At first Henderson is all journalistic professionalism and disapproving of his flamboyant American colleague, Flynn (Woody Harrelson), who is “trying to help.”

“We’re not here to help. We’re here to report.”

But soon the horrors that he sees in the city begin to involve him emotionally. He is especially shaken by a bombing which kills many in the center of the city. When his graphic footage of the dead and injured is then bumped from the lead of the news back home, he is stunned. “So this isn’t the lead story today. What is the lead story today? The second coming?”

“The Duke and Duchess of York are getting divorced,” says his producer, Jane (Kerry Fox).

This is one of several moments of irony highlighted by the filmmakers, particularly at the expense of the various world leaders who try to look as if they care and are doing something about the appalling misery of the Bosnians. Perhaps the most memorable example is their having Bobby McFerrin’s “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” playing while we watch footage of the Euroleaders arriving in the city, taking their photo-ops and mouthing their platitudes. One U.N. official in particular is savaged for claiming that the pressure of work prevents the U.N. from helping, since “there are 13 places in the world worse than Sarajevo” — which was actually probably true. “Welcome to the 14th worst place in the world,” thus becomes a sardonic catchphrase.

Soon Henderson is fully engaged in trying to do something about what he is reporting on. He tells Jane that they are going to broadcast from an orphanage they have found every day, so that they will “have kids on TV every evening saying: ‘Get me out of here.’”

“That’s not news; that’s a campaign,” Jane protests.

“What’s the matter? Big guns, evil men, little children — it’s great TV.”

Less effective than the film’s scenes among its cynical and swaggering and angry journalists, however, are the scenes which purport to show us real life among the Bosnians, represented for us by the journalists’ driver, Risto (Goran Visnjic), and his friends. We have either too much or too little of such scenes — enough to be a distraction but not enough for us really to get to know them. And they add little but generic social context to the story that most interests us, that of the nine-year-old Emira whom Henderson meets at the orphanage. With his vague assurances of a willingness to help, he somehow gives her the impression that he is going to get her out of Bosnia. As he later explains to his wife back in England: “She thought I could get her out. It occurred to me that I could. And there didn’t seem to be any reason not to.”

Those words are the essence of the film and, along with heart-tugging stock footage of the siege by real TV journalists and the briefly suspenseful tale of Emira’s escape — what makes it effective. For it is thus that real goodness so often sprouts up in the most inhospitable soil — I refer, of course, to the mind of a journalist — as somebody’s conscience is stirred to acts of charity, bravery and magnanimity merely by the reflection that there seems no particular reason not to do them. Thus when the film itself plays what Risto calls “Sarajevo’s favorite game. . . ‘Is there a God?’,” it gets, very unexpectedly, an affirmative answer.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.