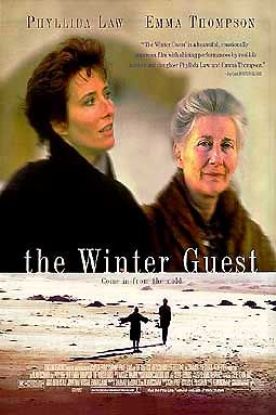

Winter Guest, The

All the way through The Winter Guest, which was directed and co-written by the fine British actor Alan Rickman, I was bothered by the fact that the action (I use the term loosely) was supposed to be taking place on “the coldest day in living memory” in East Fife, Scotland. Anyone who has ever been in East Fife knows that the people there can remember a lot of very cold days. It is so cold, indeed, that the sea is frozen. And yet, from beginning to end of the film, we see people out and about in the cold without hats or gloves, sometimes without coats or even shoes. Two schoolboys playing truant stay out in it this way all day long and never seem to feel it. The characters occasionally talk about how cold it is but when they do so their breath does not steam. The one interior we see is also said to be cold because the central heating is not working, or not working properly, yet both Emma Thompson as the lonely widow, Frances, and Arlene Cockburn as her son’s new girlfriend, Nita, think nothing of parading around in the buff. They don’t even get goose-bumps.

It is almost as if Rickman wants to rub our noses in the fact that the cold is not real cold but symbolic cold. The cold of bereavement, the cold of doubt and estrangement between Frances and her mother (played by Miss Thompson’s real-life mother, Phyllida Law) and between Frances and her son, Alexander (Gary Hollywood), whom her grief is causing her to neglect. Beyond this familial coldness there is the coldness that threatens friendship — between the two schoolboys and between two funeral-going old ladies — and the budding romance between Alexander and Nita. What the representation of the cold symbolizes to me, however, is what is wrong with the picture. It is far too writerly, too cerebral, too full of deep thinking and not enough basic attachment to reality. This Scottish village is a village of the mind, in which characters of the mind and not real people exist solely in order to be profound about life and loss and growth and extinction, all to the tune of poignant Scottish folksongs on an unseen piano.

Rickman and his co-writer, Sharman MacDonald, should have put it all in a slim volume of spiritual meditations, not a movie.

The two schoolboys, Sam (Douglas Murphy) and Tom (Sean Biggerstaff) are the worst thing about the picture. They don’t talk at all like schoolboys, or act like them. When they find a couple of kittens they mother them instead of torturing them, as they would have been more likely to do in real life. Then one boy says to the other, “Folks should have a kitten delivered every three months with the milk. . .It would make the world a better place.” No schoolboy who’s ever lived, least of all one playing truant, has ever talked like this. This is the authors’ voice by ventriloquism, which is almost as obvious in the shy courtship between Alexander and Nita and significantly less so in the bickering to and fro between Frances and her mother. This is something which is clearly nearer the experience of Ms MacDonald, who wrote the stage play on which the film is based.

There are a few good lines in these parts of the film, as when Frances threatens to move to Australia to get away from her memories of her late husband, Jamie. Since Jamie never went to Australia, she might be able to leave him behind if she went there, she says. “Go to Carnoustie,” advises her mother.

“What?”

“If you want to get away from Jamie by going where he’s never been, I’ll just bet he’s never been to Carnoustie.”

Not that, even if that were funnier, this would be enough of a reason to waste your time on this movie.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.