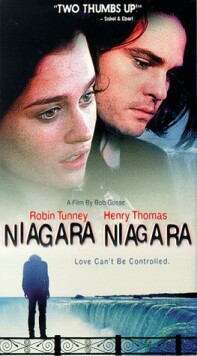

Niagara, Niagara

Niagara Niagara directed by Bob Gosse, is what we might call a sick

flick which reproduces in its title the “echolalia” or weird repetitions and

irrational tics incident to sufferers of Tourette’s Syndrome. The sufferer in

this case is a young woman called Marcy (Robin Tunney) from a wealthy but

uncaring family who meets (while both are shoplifting) a poor, lonely and

painfully shy young man called Seth (Henry Thomas). Naturally the two misfits

and outsiders team up, run away from their intolerable homes and go on a crime

spree. As a sick flick its purpose is to offer a representation of some

pathetically afflicted but still rather attractive person towards whose

sufferings we are invited to put forth a condescending compassion in order to

feel better about ourselves at no cost beyond that of the ticket and the popcorn

and an hour and a half of our time. It is actually a kind of moral therapy, one

might almost say. The filmmaker’s godlike powers are stretched forth to create a

sickness on the screen which will treat, homeopathically, the audience’s

inadequate self-esteem, since they will give themselves credit for feeling sorry

for the sick person.

All this has nothing to do with art, whose purpose is not to make us more

complacent and satisfied with ourselves but the reverse. To make matters worse,

the sickness is in this case all tied up with once-fashionable but long

discredited ideas about the “root causes” of crime—in poverty and abuse

and illness and addiction. We are meant to take Marcy’s need to forge

prescriptions or rob drug stores for medication to control her illness for

granted, yet there is no apparent reason why she cannot get a legitimate

prescription. And her self-medication with Bourbon seems more an affectation

than anything remotely likely to help, as she insists it does. Likewise the

whimsicality of the kids’ mission, to bring back home (to upstate New York) from

Toronto a hairdresser’s styling head in black is partly to make them

attractively zany and partly to suggest that the apparent absence of such a head

in New York state is, as Seth says, a sign of racism.

While burglarizing a drug store, they are attacked by the owner with a

shotgun. Seth is wounded in the leg. The owner also shoots out a tire as they

are getting away and, some way out of town, they crash Seth’s car. Next morning,

no one else’s having traveled the road since, along comes a tow truck operated

by Walter (Michael Parks). Walter, seeing that the kids are in trouble, tows

their car back to his junk yard and crushes it. Walter lives alone in a shack of

a house with Bobby Kennedy’s photo on the wall, so you can tell that he is going

to be a gruff but tender father figure to the little lost kids whose own parents

are criminal (Marcy) or crazy and abusive (Seth). He takes the buckshot out of

Seth’s leg and then takes him fishing, even though Seth is so shy that he is

even afraid of worms. “Man’s scared of worms he’s scared of worms,” says Walter

matter of factly. “He’s got every goddamned right to be.”

Walter uses the word “goddamned” a lot, as a sign perhaps that he, too, has

been crushed by life’s unfairness. “It’s a hard goddamned road to walk, that

straight and narrow,” he says. “They’re a couple of kids without a Chinaman’s

chance.” And he weeps. So then, you can guess what’s coming. It’s a cruel, cruel

world that won’t let young folks rob drugstores and gas stations or create

public disturbances in peace. The young people’s one moment of idyllic

happiness, as they stop over in Niagara Falls on their way into Canada, is meant

to stand as a moving portrait of doomed young love—that of a sort of

modern-day Romeo and Juliet. But the director has neglected to provide any

explanation for the criminal behavior which brings about their tragedy. Details,

details.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.