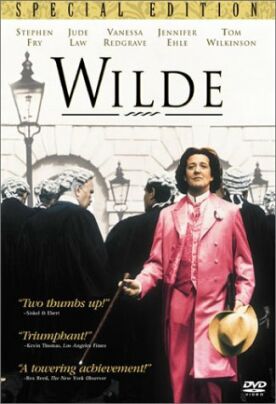

Wilde

Poor Oscar Wilde! In death as in life he has been defined by his sexuality. To his contemporaries, all that mattered about him was his passion for a stupid and ungrateful youth, Lord Alfred, “Bosie” Douglas (here played by Jude Law), and the scandal of his prosecution for indecency. Then he was a sexual villain; now — as Wilde, the adaptation of Richard Ellman’s biography by Julian Mitchell (writer) and Brian Gilbert (director), can hardly be faulted for stressing — he is a sexual hero, saint and martyr. Wilde himself would likely have been the first to point out that there is not much to choose between the two roles, particularly since death has put him out of the reach of their practical consequences. Obviously, there was much more to him than his sex life, let alone this one indulgence of it, and he might have hoped that posterity would judge him for his writing and not his private life.

It was not to be. We, no less than the Victorians, care for nothing about him so much as his homosexuality. That much, I suppose, was built into Wilde before a single word was written or a single frame shot. But the most surprising thing about the film to me was how poor Stephen Fry is in the title role. As a large, witty, multi-talented public figure of well-publicized homosexual orientation who even looks a bit like Wilde, he would seem to have been born to play the part. Yet somehow his impersonation just does not bring Wilde to life. He has only one facial expression — something between a smirk and a full-lipped pout — and he delivers the too much anticipated witty lines (nothing he could do about that, of course) like an automaton. Altogether, Fry seems too much in awe of his character, too respectful of his heroic status in the mythology of the sexual revolution, to get inside his skin and present him as a believable human being.

One place to start might have been his accent. Surviving recordings suggest that Wilde spoke with an Irish accent, yet Fry is all English. At the birth of his first son he announces in an exaggerated Irish brogue: “A new Wilde for the world; a new genius for Ireland.” To be sure, this mockery is not un-Wildean — a joke against himself for his provincial origins as much as against Irish romanticism — but it comes from outside, obscuring the fact that Wilde was an Irish romantic himself. Vanessa Redgrave in the role of his mother does speak in an Irish accent throughout and makes frequent reference to the “philistine” English. She is obviously meant to be seen as rather a silly woman, if also sympathetic, and her bringing this off is one indication of how much stronger her acting is than Fry’s who can only present to us the picture of wounded innocence.

Some readers may be offended by the homosexual love scenes, which are frequent and unavoidable. I thought they were mostly tastefully done — doubtless in pursuit of the “R” rating — though rather too much in a way to make them familiar to the contemporary “gay” community rather than to help us understand what they must have meant to Wilde in his own time, when such things had many different connotations — of classicism and art and refinement and exoticism — which have mostly rubbed off during the intervening century. Likewise, the Marquis of Queensbury (Tom Wilkinson), Bosie’s father, is a bit too much the contemporary gay-basher. There is no attempt to put him into any kind of social context, so the jeering crowds when Wilde is convicted are just from stock, a given in the presentation of any martyr.

It was a charming idea to punctuate the film with Fry’s reading of Wilde’s “Selfish Giant” — intended as an ironic commentary on his neglect of his wife and children. So too, his blistering indictment of the monster marquis’s neglect of his children makes the same ironic point. It is a creditable and a sensitive thought and replete with the kind of “family values” that the uncharitable might say the film lacks elsewhere, but it also strikes something of a jarring note. As Bosie would have said, it’s dreadfully middle class. So too, for that matter is Wilde’s very up-to-date remark: “Whatever our natures are, we must fulfill them or our lives — my life — will be filled with dishonesty.” Can he really have said anything so banal and un-Wildean? Or is it just Julian Mitchell completing his canonization as a gay saint?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.