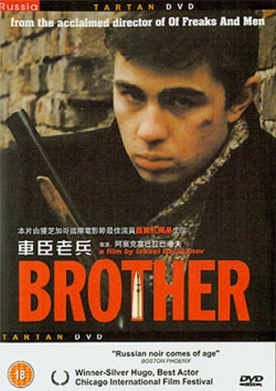

Brother

Brother, a Russian film written and directed by Alexei Balabanov, stars Sergei Bodrov, Jr, as Danila, a recently discharged soldier at a loose end who makes his way to St. Petersburg where his brother, Viktor (Victor Suhorukov) is somebody in the burgeoning underworld of Russia’s second city. The city itself is a main character in the film, much of which has rather tediously to do with an exposition of “the way we live now” in post-Communist Russia. Petersburg is seen as being on the periphery of the Russian underworld. The real power is in Moscow, but here as much as anywhere in the country life is hard, brutal and often short, a weird mixture of familiar American cultural landmarks (McDonalds, the Sony discman and the ubiquitous youth culture) and a Russian version of Dodge City or Tombstone in the late 19th century—or perhaps Chicago in the 1920s—familiar from classic movies.

There is some doubt as to whether Dodge City or Tombstone or even Chicago in real life were altogether like their representations in the movies, and the same is true of contemporary Russia. No one doubts that the much-storied Russian mafia of the post-Cold War exists, but the romance and the mythology of it—and of the poor, lone-wolf heroes like Danila who go up against it—are essentially movie phenomena. This makes it difficult for Balabanov to give us an authentic-looking and sounding vignette of Russian life. One moment when he manages it comes as Danila, just arrived in St Petersburg, goes to a record shop in search of a recording of a song that he particularly likes. When the clerk in the obviously well-stocked shop tells him they’re out of it, he automatically asks that sad, Soviet-era question: “Do you have anything else?”

“Of course,” the slightly younger clerk answers, uncomprehendingly.

The plot concerns a local mafia chief’s hiring Viktor to kill a rival while planning to kill him rather than pay his price for the contract. But Viktor subcontracts the job to his little brother, who has told him that he spent his military service as a clerical employee at HQ. When the goons make as if to kill him, he shows that he has hidden depths. Viktor is impressed with Danila’s performance and suggests that they go into business together as the Bogrov Brothers.

“What would we do?” asks Danila.

Looking at him as if he is an idiot, his brother says: “Business.”

The only problem with the scheme is the competition, since the mafia chief is now gunning for both of them. Danila is on the run, his brother in hiding, and as the thugs close in there are more comically horrifying and horrifyingly comic adventures in the Russian style, which are the more strikingly horrifying and comic to us for the familiar context afforded by the international version of American pop culture. The brothers must measure themselves and each other against the tough standards of Petersburg (if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere) before moving on, either back to the provincial hell-hole from which they came or to the big leagues of mob-violence and corruption. Such are the choices for ambitious young men in Russia today. Or so it pleases the movies to suppose.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.