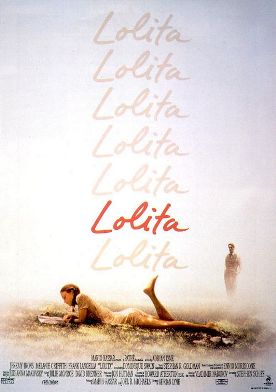

Lolita

The American distributors who refused an American market to Adrian Lyne’s new film version of Lolita until it was already booked for its first run on Showtime, the cable network (beginning on August 2), said that they did so on the grounds that the film was no good. Of course, these are the same people who voted Titanic the best movie of 1997, so we don’t want to pay too much attention to what they may say on the subject of aesthetic quality in movies, but I think there could be other reasons why they didn’t like it. Some, I think, are simply incapable of imagining a filmic depiction of pedophilia which was not also an apology for pedophilia. This is like saying that Macbeth is an apology for regicide or Huckleberry Finn for slavery. It is a kind of literal-mindedness to rank with that of the man who thought that the Biblical saying, “the fool hath said in his heart, ‘there is no god,’” was a profession of atheism.

Nabokov’s novel, written in the days before the national hysteria about “child abuse,” is certainly not an apology for the pedophilia of his hero, Humbert Humbert, but its focus is more diffuse than just condemning it. Mr Lyne’s movie, from an adaptation of the novel by Stephen Schiff, pulls together a lot of that diffusion and focuses, most convincingly and most eloquently, on America’s post-war sexualization of childhood. I think it is really this which the Hollywood bigwigs resented. When you are in the business of selling sex to teenagers, you probably don’t much want to see the ugly results of your trade as they appear in this very moving and very disturbing film.

It does have its flaws. Jeremy Irons is too good-looking, too buff, too film-starrish to be quite right for Humbert Humbert. He does a good job with the part, but one can never quite get over the fact that physically he does not present the kind of contrast with the Americans that he should do. James Mason in Stanley Kubrick’s version of the novel in 1962, though he was terrifically good-looking himself, did a better job of physically representing the Old World, simultaneously shocked and titillated by the new. More seriously, Melanie Griffith is all wrong for the part of Lolita’s mother, Charlotte Haze. She is too much the baby-doll in voice and appearance to be the blowsy, boozy, vulgar Charlotte. Shelly Winters in Kubrick’s version is again much nearer the mark. Apart from anything else, there are several references to how fat she is supposed to be, and Miss Griffith is positively wraith-like.

But these flaws are rendered almost negligible by the stunning, electrifying performance of Dominique Swain in the title role. One is tempted to ask, along with the pornographer and Humbert’s alter ego Clare Quilty (Frank Langella), “Where did you find her?” At least one can understand the American distributors’ mistake to some extent after watching her tease and seduce her stepfather in one of the most disturbing displays of ingenuous sexuality I have ever seen. I had thought myself unshockable by this time, but this is genuinely shocking. It is all one can do not to avert one’s gaze.

This Lyne does not allow us to do. With garish, kandy-kolored cinematography and an almost slapstick sort of bawdiness full of visual puns and double entendres (mum to Hum as Dolly Lo sits on his lap one evening: “Is she keeping you up?” ), he rubs our noses in this child’s corruption and in our own (and her) shameful shamelessness about it. Only Humbert the pervert is allowed to act as the voice of what have come to be called “traditional values”—to be shocked at Beardsley Prep school’s neglect of academics for the sake of “the three Ds: Dramatics, Dancing and Dating” or to warn Lolita against Clare Quilty by saying: “You’re very young and you don’t realize how people can take advantage of you.” Such ironies are a savage commentary on the world in which, increasingly, American children have grown up since the invention of the teenager and are understandably upsetting to the Hollywood types who have done so much to create it.

The general dislike of critics for the movie is a little harder to fathom, though it is true to say that they, and indeed all of us who continue to go to movies and buy CDs and watch TV, are more or less complicit in the entertainment business’s self-interested sexualization of childhood. Our defensiveness about it contrasts interestingly with Humbert’s guilt when, in narrative voiceover, he describes the night of his first sexual experience with Lolita at the Enchanted Hunter Hotel by saying of his stroll while Lolita got into bed, “I was completely happy. My only regret was that I did not deposit key number 342 at the desk, leave the hotel, the town, the country and the planet that night.” Later, as he sat with her in the car, he reflects that “It was as if I were sitting with the small ghost of somebody I’d just killed.”

If we have the imaginative capacity to feel sympathy for such guilt, I do not see how it is possible not to acknowledge our own share in the general loosening of disciplinary standards that made his sin possible. Nabokov sometimes tempted us to see Humbert as a case history, a sicko whose idiosyncratically twisted psyche could be contemplated as something apart from ourselves, a curiosity. It let us off the hook. Lyne, though he includes a perfunctory passage on the theory of the “nymphet” and the episode from Humbert’s childhood which is supposed to have imprinted his perversion on him, is much more successful at presenting his fallen hero as Everyman—and his sad little victim as Everyteen, whose innocence is a perpetual sacrifice to the gods of our still largely unquestioned sexual revolution.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.