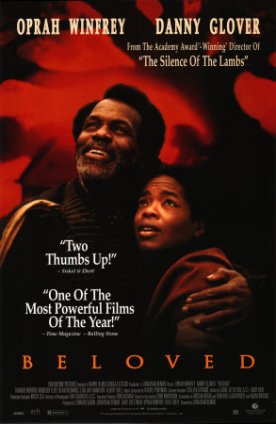

Beloved

Beloved, from the novel by Toni Morrison and directed by Jonathan Demme, exploits the sufferings of black people under slavery on behalf of a radical feminism that is merely parasitical upon them. Blacks in general and black men in particular ought to resent having their own history hijacked in this way, and used in the furtherance of a political agenda whose potential for the destruction of black community is at least as great as that of slavery itself.

It will be objected that the sufferings of women under the yoke of slavery were uniquely horrible, since white men had the power not only to enslave them but also to abuse them sexually, which is true. But that suffering they owed to their status as slaves, not as women (since if they had been part of a free and equal people their attackers could not have assaulted them with impunity), and the only way to protect themselves from it—the slow and painful struggles of black people over the last century to achieve fully human status in the eyes of the ruling establishment—has always been black men’s struggle as much as black women’s. Black women may adopt the feminist agenda of their white sisters, but it is disingenuous and dishonest and trivializing of the sufferings of their race as a whole for them to use the legacy of slavery as an argument for that agenda.

Not that Toni Morrison is much of an arguer. She is satisfied in her role as mythmaker—a role equally if not more essential to the propaganda effort—and Jonathan Demme is more than happy to assist her in it. For those who don’t know the story, Sethe (Oprah Winfrey), an escaped slave in southern Ohio “on the outskirts of Cincinnati,” turns black Medea when the hated “Schoolteacher”—the slave overseer back at the plantation she escaped from in Kentucky, “Sweet Home,” turns up with a couple of goons at her door, looking for her and the children she took with her when she stole herself out of slavery. Rather than allow them all to be taken back to “Sweet Home” and slavery, Sethe herself murders the children, or at least one of them, with a saw. “I put my babies where they be safe; I’d rather they be at peace in heaven than in hell here on the earth.”

Now there is a committed ideologue! Slavery, to be sure, was no day at the beach, but most slaves demonstrably did prefer it to haggling their throats open with a rusty saw. Not to allow her own children even the choice between these two most unpleasant alternatives bespeaks a fanatical and dictatorial temperament and one that, in spite of perfunctory attempts at ambiguity (“You don’t just kill your children,” says one of a chorus of black matrons), we are clearly being called upon to admire. And the ideology in which it is employed also emerges pretty clearly. The savage irony of attributing all these horrors to the even greater horror of “Sweet Home” is a familiar feminist trope. The words themselves suggest the sentimental domesticity of Stephen Foster (not to say Ozzie and Harriet)—something which has always held a peculiar terror for feminists.

Moreover Sethe’s escape from it is toward not only the free state across the river but her witchy mother-in-law, Baby Sugg (Beah Richards), who acts as priestess at weird “woodland services” that involve laughing and dancing but little or no reference to Christianity or the Bible. Moreover, the murder of the children (with a saw yet!) inevitably brings to mind abortion, which seems to have the property of a sacred rite as well as right to some feminists. And, like abortion, it sets momma free, since the slavers are so shocked at what she has done that they leave her alone. “Animal!” spits the loathsome “Schoolteacher,” whose own name is redolent of childish innocence gone horribly wrong.

All these events are not revealed to us until three-quarters of the way through the movie, after we have sat through two hours of what, chronologically, is supposed to have followed them. Baby Sugg dies and the two surviving boy children leave home for the peripatetic existence common among black men in the post-Civil War period. Sethe and her remaining daughter, Denver (Kimberly Elise) live on alone in the old house, now haunted by a poltergeist who is thought to be the ghost of the murdered girl-child. Sethe refuses to leave. She is later joined there by Paul D (Danny Glover), a former fellow-slave at Sweet Home who does not know about the murders 18 years before but is prepared to endure the unexplained poltergeist with the two women in return for being allowed to settle in with them and assume the role of paterfamilias.

He also gives her a chance to relive again and again the sufferings she endured at Sweet Home. “How come everybody who run off from Sweet Home can’t stop talking about it?” asks Denver. She may well ask! In spite of Sethe’s avowed intention to “keep the past from my yard,” she clings to it as if it were her reason for living. “I got a tree on my back and a haint in my house and nothing in between but the daughter I’m holdin’ in my arms,” she says. “I’m not running from anything ever again.” But both the “haint” (or ghost) and the “tree” formed by the pattern of permanent scars on her back left by a whipping administered at Sweet Home are grim reminders of the past that also validate her status as martyr to a cruel oppression seen as essentially male as well as white.

Interestingly, what she seems to mind even more than the whipping is that the white boys of Sweet Home “took my milk.” She was nursing at the time, and we are presented with a lurid flashback shot in which the two youths are lapping at her engorged dugs. Clearly there are some weirdly significant images rattling around in this broken biscuit tin of feminist treats. But it is when we get to the touches of “magic realism” that the thing really begins to get tedious. After a while, the poltergeist stops hurling crockery around and Sethe wonders if she is at last free of the burden of this guilt. Denver says that the “baby ghost” is not so easy to be got rid of. “I think the baby ain’t gone; I think the baby got plans.”

And, indeed, the baby does have plans. Soon they find in their yard an unaccountably well-dressed homeless girl of 18 or 20 who calls herself Beloved (Thandie Newton), who drools and is incontinent and can scarcely speak, walk or feed herself. Guess who this turns out to be? A weird red light signifies to us her Satanic connections. This is only one of many indications that Mr Demme and Miss Winfrey and their collaborators have seen too many movies and not enough real life, especially as it was lived by their ancestors. Paradoxically, it may be that that makes them the perfect adaptors of Toni Morrison’s ideological novel.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.