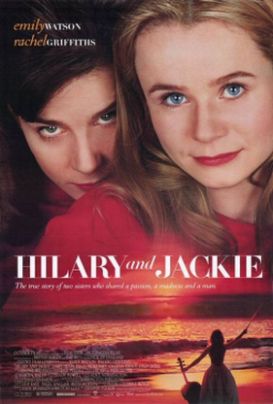

Hilary and Jackie

Hilary and Jackie, directed by Anand Tucker from a screenplay by Frank Cottrell Boyce and based on the memoir A Genius In the Family by Hilary and Piers du Pré is a guilty pleasure. It is a pleasure because it is marvelously written, acted and directed, but it is a guilty one because a lot of people who knew Jacqueline du Pré, the brilliant young British cellist who was struck down by multiple sclerosis in 1973, when she was only 28, say that it is not true to the Jackie they knew. In particular, it portrays her has having been neurotic, selfish and cruel to her sister (who wrote the book and therefore gives it her point of view) when, by all other accounts, she was remarkably gentle and sweet-tempered. This is one of the problems with making a biopic about someone whom lots of people still alive remember well. Or maybe it’s just one of the problems with biopics. Real life can never be transferred to the silver screen without some falsification.

Still, it is a kind of falsification that we would applaud in a fictional treatment of the same themes. Without it, we should not have had the memorable performance of Emily Watson as the doomed Jackie, nor yet Rachel Griffiths, the very attractive Australian actress who was second banana to Toni Collette in Muriel’s Wedding and who does a terrific job in a similar role here as the older sister, Hilary. We should not have had, either, the movie’s fresh and original commentary on the 1960s, the most boringly over-analyzed decade in history. Sex, drugs and rock’n’roll as traditionally understood hardly even make an appearance here. There is just one tiny scene in which Jackie and her husband, Daniel Barenboim (James Frain), interrupt their rehearsal of a Beethoven chamber piece to play the introduction to the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me” as a joke.

Yet the decade and its spirit are never far to seek. When Hilary tells Jackie that she’s getting married, Jackie is annoyed. “That’s just silly,” she says. “You don’t have to marry him,” and she shows her a diaphragm or “Dutch cap” that will allow her to screw anyone she likes without getting married. “Let’s get a flat together and go bonkers,” says Jackie. “Going bonkers” with passion in her playing was also Jackie’s trademark as a cellist and one that the movies naturally know what to do with—though some will wish there could have been a little less of the Elgar Cello Concerto—apparently the one recording of the actual Jackie that the filmmakers could get permission to use—and a little more of some other passionate music. It all helps to create a sense of the 1960s as a new romantic age—when Jackie marries Barenboim they are said to be “the Arthur and Guinivere of music’s Camelot”—where all the old constraints have been thrown off. Of course it’s a disaster.

For me, the theme of the sibling rivalry between the two girls is a trifling one in comparison—partly, perhaps, because it seems so much more self-serving, coming as it does from the still somewhat-embittered survivor. But even this relationship helps to expand the theme of 60s expansiveness, as Hilary is the buttoned-up and conventional musician and person and therefore someone who stands for all that Jackie has rejected with her “overemphatic body movements”—as one contest-judge puts it. When Hilary tries to put a little of this observable passion into her playing, she fails miserably. We realize that it also takes talent to make the absence of emotional constraint look attractive. One of the most harrowing scenes in the film comes near the end as Jackie is in the last stages of her illness and her thrashing around, hurling her long blonde hair about in the throes of a nervous meltdown, is inescapably reminiscent of the passion for which she had been so famous in playing her cello.

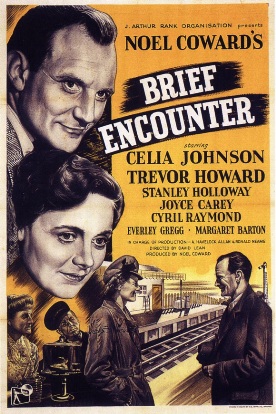

In addition to the star turns of the two principals, Charles Dance and Celia Imrie are wonderful—and wonderfully comic—as the du Pré parents, and David Morrissey does a superb job as Kiffer Finzi, the young man who is, wonderful to say, more interested in Hilary than in her beautiful superstar of a sister, but then is seduced by the superstar who cannot bear for her sister to have anything she doesn’t have. This, as I say, would strike me as being a bit over the top even if it were not agreed by a lot of Jackie’s surviving friends to be false to her memory—which is not quite the same thing, one gathers, as saying it didn’t happen. Yet the intersection of unbridled emotionalism, sexual liberation and the cult of celebrity in the life of a beautiful but doomed young girl is a compelling theme and very much one for our times.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.