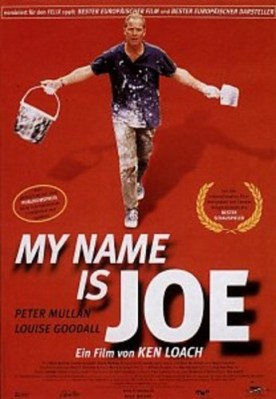

My Name is Joe

My Name is Joe, written by Paul Laverty (in Glaswegian with English subtitles) and directed by Ken Loach, stars Peter Mullan as the title character, an unemployed laborer (a surprisingly unobtrusive reminder of Loach’s usual left wing themes) and recovering alcoholic who is introduced to us at an AA meeting. He is now ashamed that, in the days of his boozing, he could see others in trouble and “didn’t give a toss,” though it is not entirely clear if this is what has inspired him to get sober. At any rate, he is a man of some moral seriousness, which is the more necessary as there is virtually no social life in Glasgow that does not involve drinking. When he meets the pretty health visitor, Sarah (Louise Goodall), who is a couple of rungs further up the social ladder than he is, he has to learn how to hang wallpaper and to bowl just so as to have an opportunity of meeting her.

Their meetings are nothing if not cute, and even the founding of a romantic relationship on pity by a member of a “caring” profession for Joe’s battles with the booze does not seem too irksome. At one point they are listening to the Beethoven violin concerto on Joe’s boom box, and he tells the story of how, once when he was drinking, he stole a bunch of cassettes and went down to the pub to sell them one by one for drinks. This was the only one he couldn’t unload. Not even for 25 pence. So he brought it home and listened to it and was bowled over by its loveliness. Yet instead of seeing in it something which gives him a glimpse of splendors beyond the squalor of his world, he now sees it as reminding him of the good times he had while drinking—a sort of alcohol-free substitute high.

It is on this occasion that Sarah asks him why he quit drinking. “I don’t want to tell you because I’m afraid you’ll hate me,” he says. But he tells her. While drunk he beat and kicked his female companion of the time. “You’ve never forgiven yourself?” she asks. “I know about that as well.” It is a hint which is never subsequently explained, but for the moment all it is required to do is get the two of them into bed together, which it duly does.

Joe passes the time while seeming to take unemployment for granted coaching a soccer team. One of his players, Liam (Davie McKay), he is encouraging with an ex-addict’s missionary fervor to beat a drug problem, for which he has already spent some time in prison. And Liam, like Joe, is fighting his way back to sobriety and decency. But Liam’s girlfriend, Sabine (Anne-Marie Kennedy), with whom he has a small child, is less successful and has landed the couple in debt to a local drug-dealer and loan shark called McGowan (David Hayman). Liam cannot pay, McGowan cannot let him off paying without breaking Liam’s legs or losing his business (“I’d be a laughingstock,” he says. “Everyone would be having a go”) and Joe cannot help except by agreeing to run drugs for McGowan—which he knows will spell the end of his burgeoning relationship with Sarah.

There is a heart-rending moment in which Joe tries to explain to Sarah, to make her understand that not everybody lives in her “nice, tidy world” where you can go to the police when you are threatened, or take out a bank loan when you are in debt, or even, if things get really bad, go somewhere else. “Some of us don’t have a f***ing choice,” he cries—and we recognize the sense in which this is true at the same moment when Joe himself recognizes the connection between that plea and the sort of things he used to say in the days when he was drinking. He sets about trying to break his dependency on the subculture of petty crime and drugs and the local and childhood loyalties that help make it so resistant to change and does so with the same determination that he brought to beating the booze.

But, like the booze, all these things are so much a part of who he is that it remains a question in the end if it is even possible for him to uproot them. The social dimension to Joe’s dilemma is introduced in a typically effective but understated form when Joe’s drug run takes him to the Highlands. He and a girl selling tea from a trailer watch a scrawny bagpiper playing for some tourists and having his photograph taken with them. He only knows three tunes, the tea lady tells Joe—and adds, perhaps resentful of the competition, that he sells them Scottish shortbread. “Bonnie Scotland, eh?” she asks.

“Bonnie Scotland, right enough,” replies Joe.

The reality behind Bonnie Scotland is drugs and idleness and drunkenness and violence on the one hand and the bland gentrification of Sarah’s world on the other, yet the words are pronounced with some affection as well as irony—perhaps because, like Scotland, Joe is simultaneously trying to be himself and somebody else entirely.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.