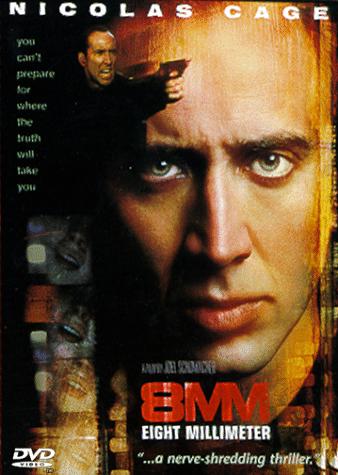

8mm

8mm, directed by Joel Schumacher stars Nicholas Cage as Tom Wells, a

private investigator engaged by an elderly widow to find out the truth about an

8mm film she has found among her late husband’s effects. On the film there

appears to be recorded the violent death of a young girl, murdered before our

eyes with a knife by a man in a leather hood. Wells, apparently unaware that he

is in a movie himself, explains to the widow that “snuff” films are “an urban

myth” and do not exist. But of course, as he is in a movie, we know at

once that he is going to discover that they do exist. Or at least this

one does. We also know that he will find, in fairly short order, the family of

the victim as well as the filmmakers and the murderer, and that his encounter

with the latter will be extremely unpleasant for all concerned.

But it is not just because we know immediately what is going to happen that

this is a boring film. It is a boring film because it does not make us believe

in the evil that it represents to us. Doubtless there are people who are excited

by violent pornography, but both they and the pornographers come off here as

mere sickos, living in a sordid and disgusting world that is not even remotely

attractive or titillating. Schumacher presumably knows the dramatic problem this

presents. Movies about sick people may evoke pity or patronizing feelings or

self-righteousness, but they do not encourage the audience to identify their

experience with its own. He presumably knows this because he makes some

half-hearted efforts to suggest that his hero, Tom Wells, is himself drawn into

the evil that he is investigating.

Wells flies to Los Angeles where the victim had been planning to go to become

a star in Hollywood and gets help navigating his way around the “adult” movie

trade from a porn shop attendant called Max California (Joaquin Phoenix). Max is

the kind of guy who reads In Cold Blood behind his ostensible porn

paperback so he won’t “be embarrassed in front of your fellow perverts,” as

Wells says—though I’m not sure that that book is all that much of an

improvement on violent porn. But Max warns him that “Things you’re going to see.

. .get into your head. . . [and]

before you know it, you’re in it. . .You dance with the devil, the devil

don’t change. The devil changes you.” Later Max asks Wells if he gets turned on

by all the stuff he has been watching. Wells says no. “But you don’t exactly get

turned off either,” says Max. “The devil’s changing you already.”

Is he? We have another indication in Wells’s curious relationship with his

wife (Catherine Keener). When we meet him he is the uxorious type and dotes on

his baby daughter, though the wife seems to be a Hillary Clinton type and is

constantly alert for signs that Wells has been smoking. He denies, Bill like,

that he “is” smoking, but continues to sneak cigarettes when she is not around.

When he first goes off on the trail of the moviemakers, he calls her every day,

but then he starts forgetting to call. Then he doesn’t get in touch at all. He

has also gone from an occasional quick smoke while the wife’s back is turned to

smoking like a chimney and thinking of her not at all. Is this what the devil

does when he changes you?

Alas, we never find out. If Schumacher means to create the impression that

Tom Wells has somehow been touched by evil, he fails utterly; and if he doesn’t,

then all that stuff about the devil (to say nothing of the smoking theme) is

just eyewash. In the end, his confrontation with the nasty filmmakers (James

Gandolfini and Peter Stormare) and the even nastier murderer (Chris Bauer)

leaves no room for supposing that they have left their devil’s mark on him.

True, he could be said by a moral sophisticate like Schumacher to have come

“down to their level” in taking upon himself the task of avenging the murdered

girl, but the plot supplies a good reason for this, and there is never any

suggestion that he gets any sexual thrills out of it. Too bad, as he would

appear to need some with a wife whose first thought, when he returns to her

broken and bleeding, is what he has put her through by not calling her

often enough.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.