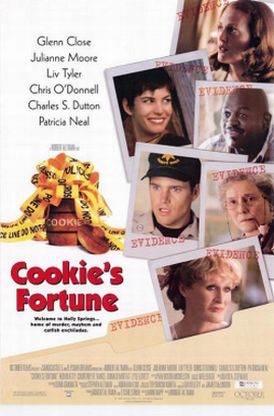

Cookie’s Fortune

Robert Altman’s new picture, Cookie’s Fortune, is like all his films in having in it a lot of good things pushed to—and usually way beyond—their limit. Here the relentless folksiness of the sleepy Mississippi town, Holly Springs, is truly charming most of the time, but on occasion it becomes almost enough to give Andy Griffith a sugar high. In Holly Springs, the catfish are always jumpin’, and we know we are about to get another heapin’ helpin’ of corn-pone when sheriff’s deputy Lester (Ned Beatty) announces that his old friend Willis (Charles S. Dutton) is innocent of the crime that hardly anybody suspects him of “because I’ve been fishin’ with him.” The movie is populated by lovable Southern eccentrics, most notably the eponymous Cookie (Patricia Neal) who smokes a pipe, works crossword puzzles and pines for her dear departed husband, Buck.

Unable to stand the separation any longer, Cookie takes matters into her own hands in one of the film’s two or three truly memorable scenes and sets its events in motion. Her snobbish spinster niece Camille (Glenn Close), who is producing an adapted version of Salome at the First Presbyterian Church (“Salome by Oscar Wilde and Camille Dixon” reads the church marquee) for Easter, happens upon the scene and decides that suicide is common and a disgrace to the family (“Only crazy people commit suicide”). She tries to make it look like a murder and robbery, which has the added benefit of allowing her to grab for herself what she thinks is the pick of the jewelry belonging to her aunt—whose real name is Jewel. An unintended side effect of her imposture, however, is that suspicion is briefly cast upon Willis, who had been Cookie’s companion and best friend.

Like so much else about the film, there is no real threat in what is potentially a threatening situation. How many movies are built around a black man’s being falsely accused of a crime by white people? The Mississippi sheriff alone is enough to build up an expectation that something of the sort is coming, and we begin with the camera’s concentrating on police patrols. Also in the film’s opening scenes we are shown other images cinematically associated with danger which are here rendered benign. An apparently drunken black man apparently breaks into a house where he surprises an old white lady on the stairs. As they meet, the glass door of a gun cabinet swings open. Someone once said that if you show a gun in Act I, you’d better show it being used in Act III. Altman does show the gun being used, but only as an act of love. Otherwise the swinging door of the gun cabinet is meant to suggest only imaginary dangers, rendered remote by Holly Springs’s sense of community.

Not that some of the folks in town are not worried about them anyway. Camille’s concern to protect the family from the taint of the “common” is meant to be seen as a similarly misapprehended danger. In particular, Camille’s overdeveloped sense of propriety and morality is the nemesis of her young niece, Emma (Liv Tyler). Emma is a free spirit with some unspecified sexual adventure in her recent past whom her aunt attempts to manage (along with every other detail of her life) on behalf of her sister, Emma’s mother, the splendidly vacuous Cora (Julianne Moore). “We pray,” goes Camille’s bed-time prayer for Emma, “that she shapes up and abandons her shameful, disgraceful and common ways.” You can probably guess whether Emma, who is sweet on junior deputy Jason (Chris O’Donnell) while being stalked by another non-threat, the creepy-but-sweet Manny (Lyle Lovett), is affected by this prayer.

The comic spectacle of Aunt Camille’s Salome may be the best thing about the movie. Its comically hopeful representation of love and death and sex and madness is another example of tragedy transmuted into comedy. I think particularly of the counterpoint to Cookie’s suicide in the overacting of Jason’s fakey-looking death in the role of a Roman soldier, despairing of the love of Salome—who is played by Cora, his sweetheart’s mother. Such complex humor helps us get over the let-down of the ending, where Altman feels it necessary to introduce family scandal, secret miscegenation and illegitimacy, and to humiliate Camille. Oughtn’t it to be enough for him that she is ridiculous without his having to make her a hypocrite as well? But the unexpected mellowness of Altman’s old age does not extend to her, apparently. The suggestion of venom in her portrayal is at least as suggestive as her priggishness of the menace he otherwise meant to leave out of Holly Springs.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.