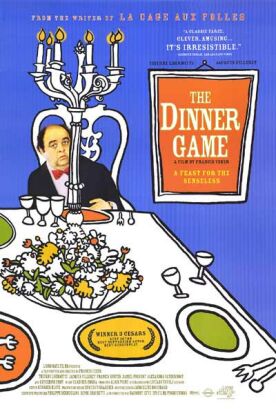

Dinner Game, The (Le Dîner de Cons)

The Dinner Game, as the untranslatable Dîner de Cons is awkwardly but decorously rendered, is an uproarious French farce by Francis Veber, co-author of La Cage Aux Folles and creator on his own of a number of other plays and films in a similar style. It tells the story of Pierre Brochant (Thierry Lhermitte), a wealthy Parisian publisher who with several friends is a member of a society devoted to competing among themselves to see who can bring the biggest fool to dinner once a week. Tipped off by a friend about a prize specimen called François Pignon (Jacques Villeret), a tax-inspector who spends his spare time building models of the Eiffel Tower and other French monuments out of matchsticks, Pierre is naturally keen to invite him to the dinner.

Villeret is a brilliant comic actor, with something of the pop-eyed, barely suppressed mania of a Buster Keaton or a Zero Mostel. Lhermitte is an equally brilliant straight-man, who registers his dismay at the series of misfortunes which befall him on account of the “idiot” just by widening his eyes a little further with each one. He is the picture of a self-consciously clever man reduced to gibbering incomprehension, which of course is his condign punishment for attempting to make sport of poor Pignon’s obvious intellectual limitations.

Pretending to be interested in publishing a book featuring photographs of the other’s matchstick creations in order to explain it, Pierre issues his invitation over the objections of his wife (Alexandra Vandernoot), who thinks that his participation in such a game is cruel and who wants to have nothing to do with it. She decides to go out on her own without meeting the idiot, who arrives at his host’s lavish Parisian apartment carrying with him his portfolio of photographs just as Pierre is ordered to bed by his doctor to rest his bad back, which he has just thrown out in a golf game.

Thus dinner itself never takes place. Instead, everything that happens comes about solely as a result of Pignon’s solicitousness about the man who had intended to make a fool of him. This fact makes Pierre’s subsequent sufferings somewhat less a source of satisfaction to us—he is being punished only for intending to mock Pignon—and encourages our sense of self-identification with him, something as important for the success of farce as it is for that of tragedy. At the same time, by showing the idiot as warm-hearted and eager to please, the film itself avoids being guilty of the same cruelty towards Pierre.

It would take too long to explain the concatenation of events which threaten to end the latter’s marriage and land him in jail, but it should be said that some of the best moments in the film belong to Daniel Prévost as Pignon’s fellow tax inspector, Lucien, who is summoned and courted because he knows the address and phone number of the man who, Pierre is convinced, is sleeping with his wife. As a portrait of petty tyranny, a man inclined to make use of his advantage in possessing privileged information, Prévost’s performance is another small comic masterpiece. Of course, he too must be brought low as a punishment for his smugness.

He also helps make the point that the heavens are just. In life it may not seem so, but farce is also like tragedy in temporarily defeating our sense of doubt that the immortals really take so much interest in our doings. How small Paris is! And, therefore, how small the world is! Everyone knows Pierre Brochant, the publisher—or the advertising man who is supposed to be cuckolding him. Pierre may have stolen his best friend’s wife, but the friend (played by Francis Huster) is somehow still around at the appropriate moment to enjoy it when he gets his comeuppance. We thus look into these people’s lives almost as of right, and our laughter is the laughter of the gods at human folly—from which, momentarily, we are thus allowed to dissociate ourselves.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.