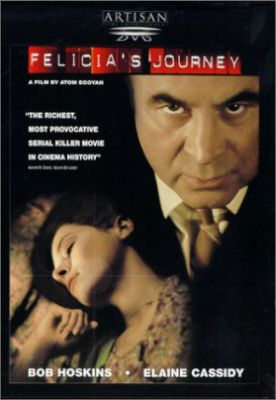

Felicia’s Journey

Felicia’s Journey ought to have all the ingredients of a terrific movie. The novel by William Trevor on which it is based is first rate, a haunting study of the banality of evil that sticks in the mind long after it is read. The director, Atom Egoyan, did a fine job with Russell Banks’s The Sweet Hereafter two years ago, and he managed to engage the services of the always-excellent Bob Hoskins in the role of Joseph Hilditch, the catering manager in a factory canteen who murders young girls in his spare time. He also found a splendid young actress called Elaine Cassidy to play the eponymous Felicia, an unmarried and pregnant Irish girl whom he has his eye on as his next victim. Egoyan’s use of the landscape of the industrial (or post-industrial) Midlands of England is also to be applauded. The movie is visually marvelous.

Yet it remains a disappointment. This is partly, I think, because of the addition that he makes to Trevor’s spare portrait in the form of Hilditch’s now deceased mother, a person whose malign influence on his life is only mentioned in a few more or less oblique hints near the end of the novel but who is here introduced to us as a third major character and, in effect, the reason for Hilditch’s being as he is. In fact, Trevor is even more straightforward than Egoyan in suggesting that sexual abuse of the son by the mother lies in the background of the former’s strange psyche, yet in the context this does not strike us as being offered as an explanation of his predatory behavior—still less as an excuse for it.

But Egoyan, by giving the mother a much more prominent role—in effect making her a third main character in the drama—does seem to fall into this trap. He imagines her as an impossibly glamorous French chef called Gala (Arsinée Kahnjian) who had her own cooking show on British television in the 1950s, and he makes her a continuing presence in her son’s life in the form of the old kinescopes of her show which he watches while working in his well-stocked kitchen—in between killing people. A considerable back-story is filled in with the help of flashbacks, in which we learn something of the relationship between this sexy, successful mother and her pudgy, unattractive son.

The result is that we experience what I can only describe as the illusion of knowledge. Egoyan cannot resist the vulgar impulse to explain “why” this man is the monster he is when no explanation is adequate to the task. It is intellectually irresponsible and even philistine of him to take the crudely therapeutic approach of suggesting, as I think Egoyan does, that Hilditch was overwhelmed by the presence of such a mother and therefore conceived a grievance against women and therefore started bumping off young girls. It’s the old story: lots of people have unhappy childhoods and don’t become murderers. And so we are left where we started, awestruck before the mystery of evil. Or at least we would be if Egoyan could resist the temptation to explain it to us.

In somewhat the same way he updates and coarsens Hilditch’s taste for popular musical kitsch. Where the novel mentions “Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra, Perry Como, Alma Cogan, Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, Eve Boswell, Doris Day and Howard Keel” the film gives us excruciatingly sentimental 1950s trash of a much more blatant sort, in particular versions of “My Special Angel” and “The Heart of a Child” that are meant to ring with a special resonance in the context, by someone called Malcolm Vaughan. This is too much like bashing us over the head with his labored thesis about the warped romanticism that possesses Hilditch’s soul. Trevor, by making his taste less execrable, allows us rather more of a share in his sentimentality—which of course makes it all the more horrifying.

Still, I don’t wish to be too hard on a film that is in many ways impressively atmospheric and remarkably well acted. I also was won over by one instance of Egoyan’s attempt to make Trevor’s view of the monster more explicit. This is in the case of Hilditch’s need to make sure that Felicia has an abortion before he kills her. “I couldn’t lay you to rest, Felicia,” he tells her almost tenderly when he has administered what he expects will be a fatal bedtime drink. “Not until you had taken care of your little one.” In the novel, the abortion is left to make its own impression, along with everything else, but Egoyan’s emphasizing it in this way not only tells us something about his killer but also something about abortion—whose creepy mixture of heartless savagery and tender solicitude so much resemble Hilditch’s.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.