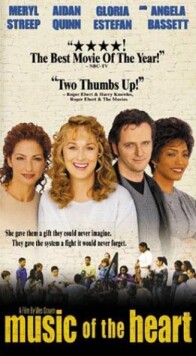

Music of the Heart

Music of the Heart is certainly heartwarming, though you may be

inclined to object, as I do, to having your heart warmed by an emotional

blast-furnace. The first non-horror flick by its director, Wes Craven, the film

is, not surprisingly, altogether too fond of the cheap emotional effect and is

constantly taking the easy routes to its feel-good conclusion, so spoiling any

illusion we might otherwise have had about the genuineness of its characters and

situations, for all that they are based on real life models. Meryl Streep in the

central role of Roberta Guasperi Demetras, a music teacher in East Harlem who

has taught thousands of ghetto kids to play the violin, is impossibly good, the

kids impossibly cute and charming; and the husband who leaves her and the

bureaucracy that cuts her funding—neither of whom we ever see—are no

less impossibly wicked for being kept resolutely offstage.

Moreover, though one must of course admire all that Mrs Demetras has

accomplished, one can’t help the feeling of being frogmarched one more time

through the evergreen romance of single motherhood. At the climax of the

picture, as Roberta and her mother (Cloris Leachman) get in a limousine to ride

to Carnegie Hall where the former and her improbably brilliant pupils are to

share a stage with Itzhak Perlman, Isaac Stern and Mark O’Connor (all of whom

naturally play themselves), mom says that she, Roberta, ought to thank Charles,

the cad of a husband who left her for some floozy a decade and more ago. “If he

hadn’t left you,” she says, “this”—meaning the chance to hobnob with

celebrities and hear herself cheered by the socially conscious music-lovers of

New York—“would never have happened.”

True enough, I suppose. But those who do not share the filmmakers’

assumptions about what are or ought to be the most important things in a woman’s

life might feel themselves brought up short by the remark. Are we really as sure

as granny seems to be that her grandchildren’s fatherlessness is amply

compensated for by a gig at Carnegie Hall? Perhaps we are. God knows, we’ve been

told so often by the movies that daddy is otiose that it would be altogether

understandable if we took it as much for granted as gran seems to do. Charles’s

dumping her may have been a temporary setback for Roberta personally, but it had

no obvious, permanent effects on the kids—both of whom are naturally,

apart from a brief moment of rebellion by one of them, model children.

But it is as pointless to complain of Hollywood’s hostility to marriage and

the family as of the savagery of a shark or a wolf. It is the creature’s nature.

And given its otherwise thoroughly Hollywoodish assumptions, the movie isn’t so

bad. Mrs Demetras, for instance, who now goes under her maiden name of Guaspari,

wins over the mother of a musical child who thinks that her son has “better

things to do than learn dead white men’s music.” She is also is a tough

no-nonsense teacher. When one little brat drags her mother into the school to

complain of being bawled out (“I’m raising Becky in a supportive environment,”

says the foolish woman), Roberta is advised by her own, otherwise supportive

principal (Angela Bassett) to go a little easier on the kids. When she tries

lying to them, and telling them that their playing really isn’t bad, they wonder

what’s the matter with her.

“Don’t you want me to be nice?” she asks them.

“I already got nice teachers,” says one little boy. “You added some variety.”

When even the brat acknowledges that being “supportive” is not all, she goes

back to teaching in the old way and tells them that they stink. Problem solved.

In the same way, when she is being cheated by those who are remodeling her

house, or her new boyfriend (Aidan Quinn) decides that he is not ready for

“commitment,” she gets tough with them and throws them out. Are we to suppose,

then, that the house remodeled itself, or that she was quite happy to remain

single until the kids placed a personal ad for her in the New York Review of

Books and found her a journalism professor (lummoxy Jay O. Sanders in what

may be the first sympathetic role of his career) content to stand back and

admire her?

Like her husbandlessness, it just doesn’t matter. The important thing is that

she makes the right gestures, the gestures appropriate to a properly heroic

single-mother. Which, of course, she always does. If being manipulated in this

way, and for political reasons, doesn’t bother you as much as it does me, you

might enjoy this movie.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.