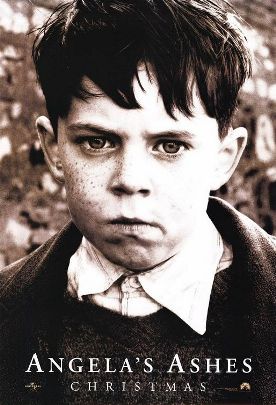

Angela’s Ashes

Alan Parker’s film version of Angela’s Ashes points up what was wrong with the best-selling memoir by Frank McCourt on which it is based. I’ll be the first to admit that McCourt’s book was a good read, but what made it one was the wry humor and skillful writing, above all its sensitive ear for the sound of Irish-English. But in terms of substance it was sadly lacking. The movie struggles against this deficiency, but finally gives up and acknowledges that it has nothing to say to us except: “These people suffered.” And so they did too. But the fact by itself is not enough to sustain a 145 minute film.

Let’s not be in any doubt about the suffering. Limerick, Ireland in the 1930s was a hell of a place to live if, like Frank (Joseph Breen), you were a small boy and your father (Robert Carlyle) was an improvident drunk or absent. Frank’s mom, Angela (Emily Watson), warned that she could go to hell for saying that “God may be good for someone, somewhere, but He hasn’t been seen lately in the lanes of Limerick,” replies, “Aren’t I there already?” Well, no actually. But it doesn’t do for those of us who live in relative comfort in another country 60 years later to point that out. And the movie reminds us of what we are more likely to be able to forget amid the delights of McCourt’s prose: the extent to which the story’s impact depends on this kind of moral blackmail.

Parker’s earlier film, The Commitments (1991), was a livelier and more interesting meditation on being poor in Ireland. Here, despite a superlative cast and the considerable trouble he has obviously gone to to recreate the look and feel—even the look of the smell—of Limerick’s poorer neighborhoods in the 1930s, he just can’t get over the fact that nothing happens. Or rather, that the only thing that happens is that things keep getting worse until near the end when the adolescent Frank (Michael Legge) gets a job, saves his money and leaves for America, “where no one has bad teeth and everybody has a lavatory” and where, presumably, things get quite a lot better.

The best thing about the movie, as about the book, is the language. “In the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Toast,” says hungry young Frank by way of blessing to a meal he seems unlikely to share. When he gets sick after his first communion, his grandmother cries: “Look what he did! He’s thrown up the body of Jesus. I’ve got God in me backyard!” A teacher at Frank’s school says, “Our Lord had no shoes. You don’t see him hanging on the cross, sporting shoes.” When, slightly older, he confesses a carnal sin, his confessor asks: “Was it with yourself or another or some class of beast?” Frank’s voiceover marvels: “This priest must have been from the country; he was opening up new worlds to me.” But, naturally enough, the language makes up a smaller part of the whole effect of the movie than it does of the book, and the rest of it makes the mistake of drawing out and milking the pathos, which overwhelms the humor here as it does not in the book.

As a result, there is too much of the besetting sin of Hollywood, which is an appeal to self-congratulation. We feel better ourselves for being able to pity poor young Frank and his family from a safe distance. “Dear God above, why do you want wee children to die?” has only a faint resonance for most of us (Thank Somebody), and so we can concentrate on our imperial mission of imposing on the past the emotional and cultural values of contemporary America. So Frank wistfully describes in voiceover his last glimpse of his father: “If I were in America, I could say: ‘I love you, dad.’ But in Ireland you could only say you love God, and babies and horses that win. Anything else is softness in the head.” Well, grumbles the curmudgeon, at least they had that going for them.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.