Boiler Room

One must naturally applaud the highly moral purpose of a movie like Boiler Room, written and directed by Ben Younger. Out of appreciation for it, one can almost ignore the rap music and the suffocating hipness and, with them, the suspicion that like its model, Wall Street, the film really glorifies what it ostensibly disapproves of, which is the get-rich-quick culture of New York stockbrokers. There is a scene here in which all the big shot brokers at the J.T. Marlin brokerage shop sit around watching a video of Wall Street and speaking the dialogue from memory. Such favorite lines as “Greed is good” and “Lunch is for wimps” live again as an ideal but Ben Younger hasn’t quite got the chutzpah of Oliver Stone. In the end, he retreats to an unconvincing, feel-good ending.

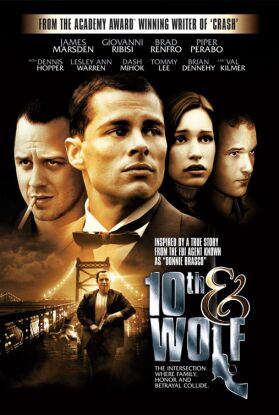

The story, much of it told in voiceover by the lost-boy hero, Seth, played by the pasty-faced man-child, Giovanni Ribisi, tells of his being goaded by his father the judge (Ron Rifkin) into giving up the illegal casino he runs out of his apartment in favor of a supposedly legitimate stock-broker’s job, only to find that his fellow stock-brokers are all crooks. “The illegal business was the most legitimate thing I had going,” he observes with Candide-like wonderment. Not that he ever considered anything but a big score. Right at the outset he tells us that getting rich quick is the only option for him. “I didn’t want to be an innovator, I just wanted in,” he says. “There’s no honor in slinging burgers at Mickey D’s; the honor’s in the dollar.”

Backing him up on this eccentric view of honor, he cites no less a thinker than the rapper, Notorious B.I.G., who is said to allow of only two routes out of the ghetto—“sling crack or get a jump shot.” Though it might be seen as pushing things just a little bit for Seth, the Jewish son of a federal judge, to identify his own attempts to find gainful employment with the hardships of ghetto life, an appreciation for rap music and black slang apparently allows you to do that without any shame over the indecorousness (not to say the absurdity) of the comparison. Thus it was, Seth tells us, that “I did the white-boy equivalent of slinging crack. I became a stockbroker.”

Well, if you swallow that, you might as well swallow the rest, up to and including the final, voiceover epiphany: “I tried slinging crack, and I never had a jump shot. Now I’ve got to get a job.” And to help the bolus go down, we have the affecting story of a reconciliation between father and son, estranged since Seth, aged ten, fell off his bicycle and his father expressed his concern for him and any possible injuries he might have sustained by slapping him across the face. “All I wanted to do was make your pain disappear,” dad explains twenty years later. “Not a single day of my life has gone by that I don’t think about that moment”—which makes you wonder why he never said anything about it before. But all’s well that ends well, and dad’s high expectations of his son seem finally to have eventuated in a search, or a prospective search, for a legitimate job.

That can’t be bad, right? Yet in the end we get the feeling that the movie is really there not for the sake of its moralizing conclusion but for the amazingly hip, obscenity-laced “greed-is-good” speeches of a character, Jim Young (Ben Affleck), who seems to have no other function. Affleck doubtless liked the dramatic potential of these colorful monologues and didn’t want to bother getting involved with the rather corny backstory.”There is no question about your becoming millionaires. The only question is how many times over,” he says to the starry-eyed trainee stockbrokers. “People who say money is the root of all evil don’t have any. . .They say money can’t make you happy, but look at the grin on my face, ear to ear, baby….You want vacation time, go teach third grade in public school…. Your parents don’t like it? ‘F*** you, mom and dad.’ See how they feel when you’re making their Lexus payments.”

And so on, and so forth. I guess that, like Notorious B.I.G.’s inspirational rap chants, this is supposed to seem cool and seductive, but you can’t help coming away feeling that anyone who, like Seth, falls for such stupidity and moral illiteracy deserves—well, rather more than he gets.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.