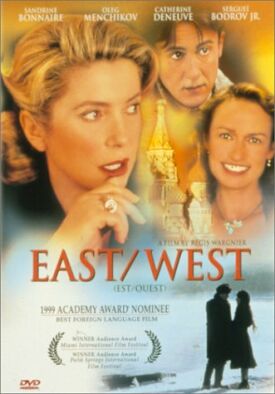

East-West (Est-Ouest)

In the New York Times‘s review of East-West, a Franco-Russian production directed by Régis Wargnier, A.O. Scott noted that, on its release in France last year, the film had been criticized for “its supposed anti-Communism” but that, it seemed to him, “its politics are fairly restrained.” How typical of the New York Times to assume that the charge of anti-Communism was discreditable to the film and then to make a virtue of its restraint! This restraint, incidentally, seems to consist in the fact that, for Scott, although the film “shows the essential monstrosity of Stalinism,” it “does not conclude that everyone who lived under it was a monster.” Well, no. But who ever did conclude that? Does not, in fact, a proper appreciation of “the essential monstrosity of Stalinism” itself assume that the people who lived under it were mostly victims and therefore, precisely, not monsters?

Actually, there is nothing restrained about this movie’s scorn for Stalinist tyranny, and a good thing too. With an almost epic sweep it shows us what happened when Stalin invited Russian exiles living in the West to come home and “help rebuild” their homeland after the devastation of the Second World War. The film begins with a party of sentimental Russians going home on an ocean liner on the Black Sea, drinking and singing Russian folk songs. The moment the ship docks in Odessa, even as a French voice announces by loudspeaker a welcome to the land “where, under the guidance of comrade Stalin, wisest of the wise, the people live as one family, happy and united,” the returnees are divided into the useful and the politically suspect. What happens to the latter is suggested when an old man, arrested on the spot, sees his son, who has never been to Russia, shot while trying to run away.

Our attention is focused on one family. Alexei Golovin (Oleg Menchikov) is a doctor who has brought his pretty young French wife, Marie (Sandrine Bonnaire) and their small son Seryosha (Ruben Tapiero) with him to begin a new life in the Soviet Union. On the boat, Alexei had paid a loving tribute to his wife for allowing herself to be uprooted from family and friends in France and accompanying him to the land of his fathers. “You must be a brave woman,” someone says to her. But soon it is made clear just what a price she has paid without realizing it. A secret policeman takes and destroys her passport and accuses her of being an “imperialist spy.” Clearly, she is headed for prison or the Gulag at best until Alexei insists that without her he will not take up the appointment he has been offered in Kiev.

It is important that Marie does not know what it took for Alexei to save her from the appalling miseries of the camps on this occasion, since throughout the film she continues to cling to her French and Western attitudes about what the government can and cannot do to her. “They can’t keep us here,” she says; “they have to let us go!” Alexei tries as delicately as he can to explain to her that it is utterly absurd of her to go on thinking in terms of what the government can and can’t do in a country where it can do anything. “Do you want to be sent to the camps?” he says. But this conveys nothing to her. In one scene of macabre humor she decides to take her complaint to the authorities in person and asks another resident of the crowded tenement where they live for the address of the Ministry of the Interior. The Russian looks at her with incomprehension. “You want to go there?” Only at the last minute does Alexei intercept her.

Because of his love for her—as well, presumably, as his shame for his country and his own folly (as anyone could now see) in bringing her there, Alexei has up until now tried to hide from her for as long as possible the abyss of suffering and degradation to which her loud complaints about their much milder inconveniences in the tenement in Kiev are bringing her ever closer. Now in front of the Interior Ministry with curious guards looking on, he whispers a promise as the only way to prevent her from making even more of a scene and getting them both arrested: “We’ll get out—somehow;” he says. “Until then we’ll have to make do.”

But the strain on their marriage proves too great. Marie lives in a perpetual state of resentment towards Alexei because of what she sees as his wilful refusal to make an effort to return to France. “The only thing I see in your eyes morning and evening is hostility,” he tells her. And, faced with her unbudgeable sense of grievance against him, he starts an affair with the woman across the hall. Marie kicks him out and herself becomes involved with a young swimmer, Sasha (Sergei Bodrov Jr.). The sexual attraction between her and this young man takes on a political dimension as he is soon inflamed by her own passion to escape. “Marie; I want to get out too—leave the country,” he tells her in what for them is love talk. “I want to help you,” she says, thrillingly. How erotic it is, for both of them, when he asks her to “tell me about France”!

Trapped herself, Marie is finally able to help Sasha get out by means of a daring ten mile swim through icy waters to a Turkish cargo vessel, but for her part in the adventure she is arrested and sent to the Gulag in spite of all that Alexei, who is now a party member, can do for her. When she is released six years later on the death of Stalin, she is obviously chastened and subdued. She and Alexei and the now teenaged Seryosha (Erwan Baynaud) are reunited, but Marie regards herself as permanently damaged. “I’m ashamed. The stench is still with me. I’ll never lose it.” Alexei tells her that “other innocents have been rehabilitated,” but she replies: “I wasn’t innocent. I’m guilty.”

Alexei’s position of trust and responsibility allows them to return for another couple of years to what passes for normal life in the Soviet Union of the1950s. Briefly we catch a glimpse of Khruschev on a primitive television set announcing that Communism is “the only hope for humanity’s future. Astonishingly, however, Alexei has not forgotten his promise in front of the Ministry of the Interior. With the help of a left-wing French actress, played by Catherine Deneuve, and all unknown to Marie, he arranges for her to escape, with Seryosha, to asylum in the French embassy in Sofia while he is on an official trip to Bulgaria. He knows that, as a Soviet citizen, he cannot accompany her; he knows that, whether or not she succeeds in getting out, he will lose everything and be sent to a labor camp himself for arranging it.

Only now does Marie realize her husband’s love for her. It is a great romantic moment that, like all romantic moments, transcends politics. But it is one of this great film’s great virtues that it never merely ignores or (pace A.O. Scott) “restrains” its political and moral understanding of Stalinism. All those who think that what Newsweek called “the war over Elián” was just about reuniting a boy with his father ought to be required to see this movie.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.