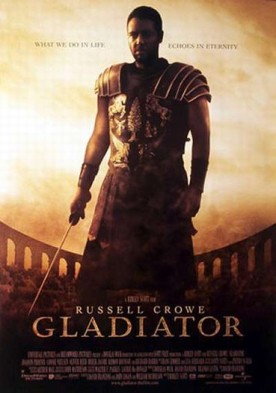

Gladiator

Gladiator, directed by Ridley Scott, is the Saving Private Ryan of the second century. Its opening battle sequence is as electrifying in its way as that of Spielberg’s film, which may have influenced this one, particularly as Gladiator comes from Spielberg’s DreamWorks. It is also a handy demonstration of the foundation of Roman hegemony under the Antonines—which, like that of America under the Clintons, was superior military technology. Unfortunately, the parallels with the present day are not really pursued. Or they are mostly pursued, in spite of some piquant hints about the Roman mob’s addiction to bread and circuses, to dead ends. For the film imagines a sort of alliance between Colin Powell, Hillary Clinton and Paul Wellstone to bring good government to Rome, which is only slightly less absurd 1800 years ago than it would be today.

The Powell figure is a great Roman general called Maximus (Russell Crowe). The historical Maximus is remembered for his closeness to his brother, Condianus, and both of them were executed in the disastrous reign of the Emperor Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix). Here, however, Maximus is represented as being alone and escaping his doom, though his wife and child are crucified. He has refused to serve under Commodus, the film’s fancy has it, because he knows that he killed his father, Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris), whom Maximus idolized for his virtue. Returning to Rome in the disguise of a gladiator, one of a stable kept by the marvelously raffish Proximus (the late Oliver Reed), Maximus allies himself with the emperor’s sister, Lucilla (Connie Nielsen) and a liberal senator, Gracchus (Derek Jacobi), to depose Commodus and restore the Roman Republic.

Doubtless there was much and regrettable “corruption” in the Roman empire, even at this period, but you’d think that Maximus would have had quite enough to fight for without also aspiring to be the Ralph Nader of Rome. Likewise, Lucilla’s transformation from the scheming sensualist she seems to have been in fact to a Hillary-like “strong woman” after the contemporary style strikes rather a jarring note. Her love for her adorably cute little boy, Lucius, her fear of what Commodus might do to him, her past romance with Maximus and the feelings that linger between them, and the psychological complexity of her relationship with her brother and of both with their father—all these things are just obtrusive enough to seem incongruously modern details without being explored in any dramatically satisfying way. In Rome, as the movies have taught us, the wickedness of the emperors, like their pomp and splendor, is better taken for granted.

And what opportunities of that kind have been lost here! Gibbon tells us of Commodus that “his hours were spent in a seraglio of three hundred beautiful women, and as many boys, of every rank, and of every province; and, wherever the arts of seduction proved ineffectual, the brutal lover had recourse to violence. The ancient historians have expatiated on these abandoned scenes of prostitution, which scorned every restraint of nature or modesty; but it would not be easy to translate their too faithful descriptions into the decency of modern language.” Just let Hollywood try, Ed! But no, Mr. Scott’s Commodus is a troubled case study, a boy who feels that his father never loved him (the historical Marcus loved him only too well) and whose only sensual passion seems to be for his sister.

Still, the old-fashioned movie style of Roman spectacle is not quite forgotten, and the picture is worth seeing for the thrilling gladiatorial contests in a computer-generated Roman Coliseum that really does impress us, almost as if we too were among the motley collection of North African provincials seeing the metropolitan center of the empire for the first time. The fights, involving exotic weaponry, chariots and even, in the climactic battle, four tigers (are there any records of tigers, as opposed to lions, in Roman arenas? perhaps a reader can enlighten me) are nearly as skilfully choreographed as the opening battle against the bearskin-clad barbarians of Germania. There is also considerable dramatic energy put into the final struggle, which takes place in the arena between Maximus and Commodus himself.

Too bad the incident isn’t true. The historical Commodus was poisoned by his favorite mistress and then strangled in his sleep by a wrestler. It makes for a better story in one way, perhaps, to have this climactic battle pointing us towards the better world of an enlightened Republican government presided over, no doubt, by cute little Lucius. But we know that that is not the Roman story, and our knowledge, it seems to me, must spoil the intended effect of any such suggestion in the movie. More promising is the idea of the first political leader on record to have confused politics and show-business. The historical Commodus fought in the arena as a gladiator 735 times and made a speciality of slaughtering lions and other wild beasts with his bow for the delectation of the crowd.

Scott’s film just touches on this most contemporary of themes, and in one memorable scene it shows us Maximus lamenting his fate to Lucilla: “The gods have spared me?” he says. But as what? “A slave with only the power to please the mob.” Lucilla looks at him as only a clever woman can look at a man who is being obtuse and says, “But that is power!” The film shows us what power it is, too, as even the tyrant Commodus must quail before the whims of the fickle crowd. This makes it all the more regrettable when the idea goes nowhere and all is reduced in the end to the far-too familiar and, in its context, faux drama of Good Government standing up in single combat against corruption, cruelty and excessive executive power. Surely the palmy days of the American Empire under Bill Clinton ought to have suggested a more interesting Roman movie than this one.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.