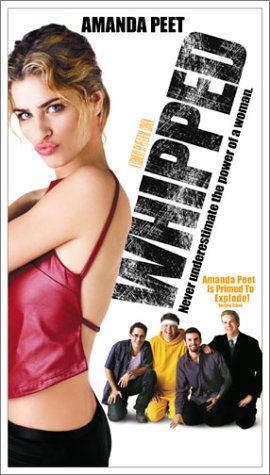

Whipped

Maybe I’m getting too old to take a continual exposure to our morally radioactive popular culture. The experience of watching Whipped, written and directed by Peter M. Cohen, produced on me the same effect that the sight of Poor Tom o’Bedlam had on the Earl of Gloucester in King Lear: “I’th’ last night’s storm I such a fellow saw/Which made me think a man a worm.” And a woman, I regret to say, maybe something a little lower than a worm. Yet the audience around me seemed to think it all delightfully funny. I suppose that, once the culture had accepted the feminist principle that men and women were to be seen as equal in all respects, a movie as loathsome as this became inevitable. But there is still some part of me which vainly expects the culture to recoil at the sight of all that is implied in that assumption, and so perhaps even to reconsider it.

This is a movie about “scamming,” which is the movie’s term (is it also current in the urban singles’ scene? readers please advise) for lying in order to obtain sexual favors. Of course men have always done this and, among themselves, have been known to boast of a deception they would be ashamed to acknowledge in mixed company. Nowadays, the lies are less potent, as they are not to persuade women that the liars love them — the women are supposed to care no more about love than the men — but only that they are “safe” to sleep with. Moreover, if we are to believe Mr Cohen, not only are the new breed of liars absurdly proud of their caddishness, but their pride is to be seen as being without offense, since women expect to be scammed and are able to scam right back. The assumption that “everybody is f***ing everybody else,” both literally and figuratively, is seen by both sexes not as a sign of moral desolation but as a glorious opportunity.

The story concerns three twenty-something boys-about-town in New York, Brad (Brian Van Holt), Zeke (Zorie Barber) and Jonathan (Jonathan Abrahams) who spend a lot of time over Sunday breakfasts in a diner rehearsing to each other their sexual conquests of the week before. Sometimes they are joined by Eric (Judah Domke), a married friend who gets vicarious thrills from the tales of their exploits and also bears witness to the woe, from the point of view of the sexually unreconstructed male, that is in marriage. There are also voiceovers and speeches to camera that seem designed to impress us with how vain, stupid, nasty and self-important all four of them are, but the context makes it clear that the author, like the boys themselves, thinks these qualities the hallmarks of “hip.”

One Sunday they all have similar stories to be reluctant to tell, for all have met a woman they “really like,” someone in whom they think they can be interested as a person. Marriage is not out of the question, though this does not prevent them from discussing her sexual attributes. We, the audience, know that they are all talking about the same woman, Mia (Amanda Peet), and therefore can guess, as the boys themselves do not until the end (though they learn pretty quickly that they are rivals in love), that Mia supposes herself to be “scamming” them in retaliation for the game she sees them playing against women. So let’s just try to reconstruct her thinking on this one: “I’ll sleep with all three of these guys, engage in wild and passionate love-making with them and then drop them, so they’ll learn what it’s like to be used for sex. That’ll teach ’em!” Even more remarkably, it does!

Of course, what it teaches them is not to treat women any differently but to stick to the original game-plan of behaving like sexual predators, since they, ex hypothesi, can also be preyed upon. As Jonathan says to the camera in the end, “it took someone as special as Mia to make us realize that women are a lot more like us — I mean like Brad and Zeke — than we thought.” And to underscore this essential point, we then see Mia bragging to a restaurant-table of her friends about what she did to all four boys (even the married one she claims to have given a blow-job to) and, in the process, belittling their respective manhoods. The girlfriends are full of admiration for her exploit which, without apparent consciousness of any double entendre, they call the work of “a f***ing pro.” The film ends with Mia saying brightly to the camera that she finds sexual scamming fun: “Guys do it all the time,” she says, so why shouldn’t she?

Why indeed? The reason, which once seemed so obvious, is now as obviously forgotten.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.