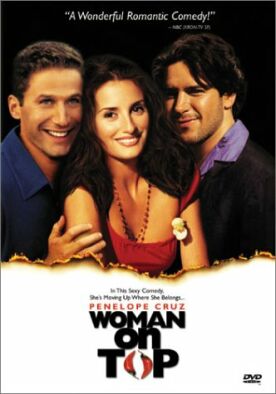

Woman on Top

Aiming for the Like Water for Chocolate niche in the market, Woman on Top is advertised as a movie about sex and cooking — which at least must be said to beat sex and shopping. Insofar as it is actually about anything, however, it is more about magic. And not very interesting magic. The magic, like the cooking, is exotically ethnic and features a Brazilian deity called Yeamanga, who seems to be a cross between one of those Mediterranean gods who causes the fish to run — or doesn’t, as the case may be — and a poltergeist. I have to say that Yeamanga is rather a bore, as most of these benevolent modern, non-smiting gods tend to be, and the rituals engaged in by his (her?) devotees are merely bizarre. But in the end, the exotic religion is of no more interest to the director, Fina Torres, or the writer, Vera Blasi, than the exotic food. Both serve merely as the by-now familiar trappings of “magical realism” so as to make (marginally) more palatable what is otherwise a pretty routine stew of romance novel and feminist fable.

The story concerns the beautiful Isabella (Penélope Cruz), who is born with a remarkable ability to cook but with what is meant to be taken as, somehow, a complementary tendency to motion sickness. So extreme is this condition that she cannot even dance or make love as a passenger, as it were, and so insists on being in the driver’s seat. “She could control her motion sickness only by controlling her motions,” the voiceover tells us: “if she always drove, if she always led, if she always was on top.” Her husband, Tonino (Murilo Benício), with whom she runs a popular seaside restaurant in Bahia, Brazil (where, oddly, they mostly seem to speak English), seems not to mind about this, but when, alerted by the ever-obliging Yeamanga, Isabella finds him screwing another woman in a more traditional fashion, he wails at her: “Isabella, I’m a man. I have to be on top sometimes!”

Needless to say, Isabella has a different view of the matter and prays to her fish-god for the strength to leave him — which is presently forthcoming. Somehow, in spite of her motion-sickness, she makes it from Brazil to San Francisco, where she stays with a drag-queen friend called “Monica” (Harold Perrineau Jr) and quickly becomes the star (along with the flamboyant Monica) of a TV cooking show. In a way the point of the thing is in the constant girl-talk with Monica who, even now that drag-queens are as common on movie sets as the grips, is obviously supposed to inspire laughter by commiserating with her about men: “They’re not like us,” she says — “romantic and loving; they’re like animals on the Discovery Channel: f***, f***, f***!” Ha ha. Get it? She’s really a man.

Naturally, Monica helps Isabella prepare an elaborate charm for Yeamanga which is supposed to uproot any lingering love for Tonino in her heart. “If I want to start a new life, I have to get him out of my head, out of my skin,” she says, and proceeds to do so. Even after the love for him is allegedly gone, however, Isabella’s wifely grievances against him continue, as so often happens in real life, and Monica serves as a sounding-board for them. Most prominent among these is not the sexual lapse but such classic feminist complaints as her feeling “smothered” and kept out of sight in the kitchen (of their restaurant) while Tonino got to greet the guests out front — especially the women.

Tonino and some Brazilian pals follow her to the city by the bay and, not to put too fine a point on it, stalk her. But Tonino is the good kind of stalker, apparently, as he soon becomes not only an equal contender for her affections with her new boyfriend, Cliff (Mark Feuerstein), the producer of her TV show, but also a regular on it, singing Brazilian sambas in the background and making eyes at Isabella while she gets on with the cooking. Cliff has to invite him on the show over Isabella’s objections when his boss decides that “he’ll be great for the ratings” and “something for the girls.” In spite of their estrangement it has to be acknowledged that “together you two have a certain chemistry.”

When the network takes an interest in the show, the suits who arrive to tailor it for a national audience obviously don’t care about the food any more than the film’s authors do, yet we are intended to wax indignant at such philistinism and applaud Isabella’s decision to pull the plug on the show. But will she subsequently get together with Cliff or return to Brazil with Tonino? Clearly the latter has learned his lesson when in desperation he cries out to her: “I want you to lead when we dance! I want you to drive the car! I want you on top! I wouldn’t want you any other way! He has to learn other things as well. “What happened to your face?” asks Isabella when she first sees him in San Francisco.

“What happened to my face?” he answers indignantly, having got into a brawl with the other patrons of a bar who were ogling her on TV. “I was defending your honor!”

“My honor doesn’t need defending!” she insists, obviously not too clear on what honor is. Not to worry. Though the film makes much of the Brazilianization of Cliff (“Isabella is Brazil, and Brazil is Isabella. . .If you want her, don’t try to understand her; you have to feel“), it is really the Americanization of Tonino that counts. Even Yeamanga seems to wish for his transformation into a compliant, American-style husband who will never insult her by defending her honor again. It’s only what you’d expect out of Hollywood, but I wonder what they think of it in Brazil?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.