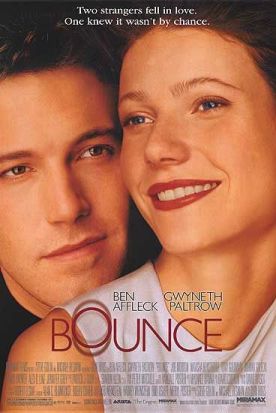

Bounce

Bounce, written and directed by Don Roos is a high concept movie. A playboy advertising executive called Buddy Amaral (Ben Affleck) gets lucky with a stunning blonde called Mimi (Natasha Henstridge) as they wait to catch the last flights out of snowbound O’Hare International in Chicago. In order to spend the night with Mimi, Buddy offers his seat on the plane to Greg Janello (Tony Goldwyn), a family man eager to get home to his wife and two sons in California over the Christmas holiday. The plane crashes with the loss of all aboard. Buddy is plunged into guilt and alcoholism, from which he is eventually rescued when he forms a relationship with the dead man’s grief-stricken widow, Abby (Gwyneth Paltrow). Only he neglects to tell her that it was his ticket which put her late husband on the fatal plane.

The point is to show us attractive people having powerful feelings—feelings strong enough to crack their outer shell of emotional continence and so to win our sympathy. It is a very basic idea for a movie but, it seems to me, rather too basic. Having engineered the tragedy and the two principal characters’ relations to it in order to show them having feelings, the movie neglects to provide them with anything much besides those feelings that might make them interesting to us. It seems a shame to have an expensive airplane crash and hundreds of people be killed just so that Buddy can be less of a jerk and Abby can find a new man and both can overcome their feelings of guilt about the death of poor Greg. The crash is such an overwhelming datum at the center of this film that the characters would have to be pretty extraordinary to fight free of this defining event in their lives. They’re not. They’re merely “survivors.”

Or, to put it another way, it’s like the old promo line from Love Story: “What can you say about a young woman who dies?” Precisely. The feelings of those who survive the victims of cancer, or of an airline crash, may be presumed to be a sort of emotional constant and therefore not interesting artistically. There is nothing to say but that they have them. Indeed, to try to say more seems exploitative and lacking in respect for those feelings. The film itself recognizes this in a funny bit where Buddy’s advertising agency tries to spin the bad PR generated by the crash in favor of the carrier with a soppy commercial paying tribute to one of the flight attendants who died in the crash. Buddy, while still in his drinking days, comments scathingly: “Kind of makes you wish you’d crash more often doesn’t it?”

This is an indication that Mr Roos really is trying hard to treat these moral problems with great sensitivity, but the task is beyond him. Instead he ends up with little more than a variation on the current clichés of movie courtship, rather similar to last spring’s Return to Me, by Bonnie Hunt. What you take away from both movies is a comfortable sense not, obviously, of the emotional hurricane at their center but of the chatter between the heroine and her Best Friend (there played by Miss Hunt herself, here by Caroline Aaron) designed to smooth the way for resumption of “normal” sexual relations. In this case, the hero also has a pal to push him in the right direction in the form of Seth (Johnny Galecki), his annoying little assistant at work . Making Seth gay is, admittedly, something of a daring departure from form, since the gay guy is usually the woman’s confidante. Even more daring is his making Seth (or anyone) a spokesman for individual responsibility and against Buddy’s easy assumption that his alcoholism is a “disease.”

But both Seth’s gayness and his strong moral sense, once established, are made little of, and the former is all but forgotten about. The initial hostility between him and Buddy never visibly dissipates enough to raise any inconvenient questions about the nature of their relationship. Seth, like Miss Aaron’s Donna, is there simply to provide the girl talk that the girls this movie has been made to appeal to have come to hear. Both concentrate on Buddy’s shortcomings, but it is Donna’s job to scold and cajole Abby into overlooking them. “Guys screw up,” she says. “It’s what they do. It’s in their manual, right after ‘Love your grill, leave your socks on the floor.’” This kind of thing is meant to be cute and funny. That, and the borderline pathos that results from putting cute and funny in the context of tragedy, is really what the movie has been made to give us. It just doesn’t seem like enough for me.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.