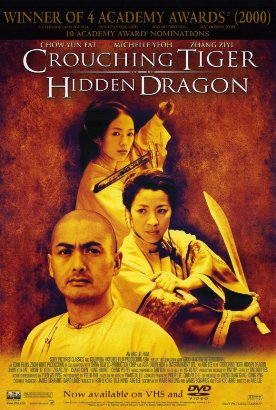

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon directed by the excellent Mr. Ang Lee is a sort of Charlie’s Angels for sophisticates. Good as Mr Lee is, one sometimes finds oneself observing of his films that they are very well done while asking oneself if, after all, they were unquestionably worth doing. So it is with this film, which mixes together a 19th century redaction of ancient Chinese legends, the movies’ long love affair with Oriental-style kick-fighting, some cinematic “magic realism” and a large dollop of Hollywood feminism in a brew which never, to my taste, takes on a flavor of its own. Or rather, insofar as it is flavored at all, it has the familiar, rotten taste of the feminist parable to which it is forever making a tentative approach before drawing back again in the direction of a more traditional love story.

We begin with the arrival of a legendary martial arts master of the even more legendary Wudan, one Li Mu Bai (Chow Yun-Fat), at the home of his old friend and adviser Shu Lien (Michelle Yeoh), who is the widow of a comrade-in-arms killed in battle. Having defeated all opponents, Li decides to retire and present his famous sword, the Green Destiny, to an old and much-revered friend, Sir Te (Lung Sihung). Shu Lien assists in the transfer. But almost immediately after its arrival at the house of Sir Te, the Green Destiny is stolen by a lithe cat-burglar who is able to perform acrobatic prodigies in escaping the pursuit of Shu Lien—herself an accomplished leaper and kicker.

It is at this point that we realize that, like the major actors, we have left the earth and will only touch down again when it is convenient for the author. The burglar and the pursuing Shu Lien leap from rooftop to rooftop in such a way as to suggest that Mr Lee and his screenwriters, Wang Hui Ling, James Schamus and Tsai Kuo Jung, are trying to bend our disbelief without quite breaking it. Never in nature have there been such leaps, but neither do the pursued nor the pursuer take to the air in full Superman style. It looks more as if they had suddenly been transported to a planet where the gravity was about a tenth of what it is on earth so that they can simply bound like kangaroos for great distances without the inconvenience of having to come down until they have attained the neighboring rooftop. When they do come down, and come face to face, they engage in a kicking, chopping sort of combat, both with and without weapons, which while remarkably graceful and athletic is itself not (at this stage anyway) redolent of the supernatural.

The fight is inconclusive, but the thief gets away. We soon learn that the cat-burglar disguise has masked a demure young aristocratic girl called Jen (Zhang Ziyi), daughter of the provincial governor, who is about to be married. She has already confided in Shu Lien, whom she professes to regard as a sister, that she is not happy. “I’m getting married soon, but I haven’t lived the life I want”—a life, she goes on to explain, characterized by freedom, especially the freedom to choose her own mate, but also adventure, “like one of the heroes I read about in books.” Now it emerges, however, that while mom and dad thought she was in school, or at least being tutored by her governess, she has already lived a life nearly as adventurous as that of Li Mu Bai, whose past is only vaguely alluded to. For the governess is in fact the notorious woman warrior, Jade Fox (Cheng Pei Pei), who has stolen the secrets of the Wudan and taught herself, and subsequently Jen, the arts of combat with which she means to avenge her sex for their exclusion by the knights of Wudan.

The suggestion of a distinctively modern parable of the relation between the sexes is carried as far as the hint of a lesbian interest by Jade Fox in her young protégé and thus, perhaps, of a budding proto-feminist cabal. At one level, the movie’s feminism could be construed as amounting to little more than some Brandy Chastain-style shirt-waving. Jade Fox and Jen, if they stand for anything, stand for Title IX funding for girls’ martial arts. But there is an underlying seriousness implied by the imagery of war. Jade Fox certainly, and maybe Jen too, not only want to compete with the boys, they want to kill them. The Green Destiny’s phallic implications—stolen by a girl!—suggest a castration anxiety for which these predatory females are only too happy to give some foundation.

But all such meanings in the story are raised only to be abandoned. Or rather, perhaps, we are invited to adopt the view of Jen herself, a beautiful and highly talented young woman who finds herself torn (as so many talented and beautiful young women do) between the feminist imperative to her left and, on the right, the comforting patronage that the masculine is always ready to extend to her. When Li Mu Bai sees her fight, he immediately recognizes her potential and asks her to consent to be his pupil. Moreover, we are also shown in long flashback Jen’s capture by desert bandits and her subsequent life among them, during which she becomes the lover of the bandit chieftain, Lo (Chang Chen). If one cannot quite imagine her barefoot and pregnant in some Mongolian mountain cave, neither is she altogether immune to the charms of a more traditionally feminine domesticity.

The problem is that the movie offers us no real option for the latter. Jen’s own mom and dad are presumably busy professionals, since they remain extremely shadowy figures on the periphery of the action and are apparently so uninvolved in her life that they don’t even notice when she has been kidnapped by bandits. And how, we wonder, did Jade Fox manage to teach her all those secrets of the Wudan right under her parents’ noses? Didn’t they ever wonder about all that kicking and leaping going on down in the rumpus room? For Jen, the established sexual order only exists in the form of Lo, who offers her a gang rather than a family, and Li’s ambiguously sexual pursuit of her. He could be another lover, or he and Shu Lien together could offer her an alternative family, though these remain only speculative alternatives.

At any rate, no decision can be made until she is prepared to break off with the wicked Jade Fox, and by the time she does this it is too late. There is a climactic battle between Li and Jade Fox, and Jen, as usual without a thought for her parents, retreats to a sort of dream-world with Lo. None of it makes any sense to me, nor have I seen any critic prepared to explain it. Rather, the movie garners kudos on the basis of its style and visual inventiveness, especially of the fight sequences which were choreographed by the guy who did them for The Matrix. The martial arts movie, we are told, will never be the same. Perhaps this is true. Those of us who had no great love for the martial arts movie in the first place (except in the witty hands—and feet—of Jackie Chan) may reflect that it is only fitting that its already tenuous connection to reality should have vanished into the clouds with Ang Lee.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.