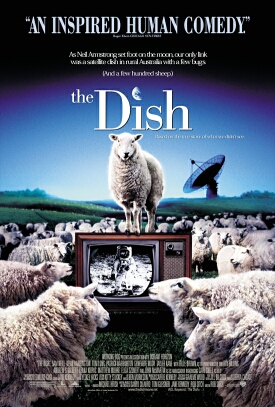

Dish, The

I’m not quite sure how it does it, but the Australian film, The Dish, directed by Rob Sitch, gives the best cinematic account known to me of the American space program. On the surface, it is only tangentially about the Apollo 11 moonshot in July, 1969. Instead it concentrates on the true story of the Keystone Kommunicators at a radio-telescope in Parkes, New South Wales, to whose lot it fell to receive the radio transmissions of Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins at the moment when Neil Armstrong takes his giant leap for mankind. At one point someone jokes that he doesn’t know “which is more important to get back, the men or the pictures,” but a recent Fox special making the case that the whole moon-landing was faked suggests that it wasn’t entirely a joke. And, as it happened, the pictures almost didn’t make it, whatever may be the case with the men. A combination of human error and bad luck very nearly put the telescope off-line at the very moment when it was the only dish in the world capable of receiving the transmission from the moon.

The ever-reliable Sam Neill plays the Australian chief of the installation, Dr. Cliff Buxton, a recent widower whose enthusiasm for the space program was imparted to him by his late wife and who now bitterly regrets that she is not here to share the big moment with him. His staff consists of the American NASA representative, Al Burnett (Patrick Warburton), a fun-loving nerd (Kevin Harrington) and an up-tight nerd (Tom Long) and a comically dim security guard (Tayler Kane). These do not exactly look like the kind of guys by whom history is made, but that’s sort of the point. If they were all smoothly efficient like the people manning all those banks of monitors in Houston in Apollo 13, they would not make the human impression on us that they do, or make the moon mission as impressive looking as it is. Cliff is speaking to us as well as his rag-tag staff when he interrupts one of their periodic bouts of complaining by saying: “NASA’s just a bigger bunch of us…This is science’s chance to be daring, and what are you doing? Standing around bitching.”

They are also standing around screwing up. When a power-failure knocks out the dish’s receiving equipment, the back-up generator fails to come on because someone forgot to prime the fuel lines and the computer is wiped. At the moment when NASA comes on the radio to ask what has happened to Parkes, the obviously decent and honorable Cliff is faced with a terrible decision. “We still have a strong signal,” he announces into the microphone. “It must be a relay problem.”

Aghast, one of the crew says: “Cliff, that’s bull****. You bull****ed NASA!”

Embarrassed but resolute, Cliff says he’s not going to let NASA think “we’re just a bunch of d***heads who can’t even keep up a practice signal.” He turns to Al: “We just need you to keep NASA off our backs for a while”—while they reprogram the computer.

“I am NASA,” says Al. But he obligingly continues the bull****ing until the signal from the spaceship is picked up again.

In addition to the staff at the dish, there are the townspeople of Parkes, who are a richly comic bunch worthy of the director of the very funny The Castle (1999). The most amusing of the townsfolk is Mayor Bob McIntyre (Ray Billing) who is every inch the overawed provincial but who stands in relation to his family and constituents rather as Cliff does to the staff at the telescope. In addition there are the Prime Minister of Australia, as funny as any of them, and the American Ambassador (John McMartin) who turns up to listen to the radio transmissions and has to be deceived, during a period when the dish is off-line, by a faked transmission from outer space. “It’s incredible,” he says to the boys at the console. “You can actually pinpoint a tiny spaceship thousands of miles away!”

“Pretty much,” says one of them uneasily.

Later, when the Ambassador is asked what Neil Armstrong sounded like, he says: “Like he was next door.” But the Ambassador is admirably diplomatic when the local band, instructed to play the American national anthem, strikes up the theme from “Hawaii 5-O.” As always, the screw-up is rather endearing and only serves to set off to advantage the magnificence of the achievement happening just off-stage.

There are also two complementary sub-plots which subtly reinforce the theme of human striving. In one a mad-keen young Australian army recruit called Keith (Matthew Moore) doggedly courts the mayor’s scornful daughter, a sullen proto-feminist called Marie (Lenka Kripac). Of the moonshot, Marie says: “If you ask me, it’s the biggest chauvinistic exercise in the history of the world.”

“That’s why nobody asks you, darling,” says her mother sweetly.

But Keith is nothing daunted even by the most withering irony. “Marie, I was wondering if you’d like to dance?” he asks her at a party.

“Are you stupid?” she replies.

“No,” says matter-of-fact Keith. “Do you want to?” Even Mayor Bob, who fought in the war, is full of admiration for Keith’s bravery.

In the other subplot, the uptight nerd from the dish lusts after a local girl who obviously fancies him, but he hasn’t the nerve even to ask her out. When he turns to Cliff for advice, the latter obligingly sums up for us what the film has to say: “Sometimes you’ve got to take a risk.”

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.