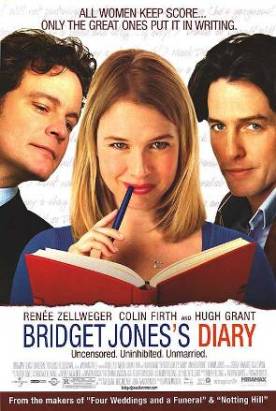

Bridget Jones’s Diary

What is it that has lately induced the makers of romantic movie comedies think of Jane Austen as the Everest of their ambition? Now we can add Bridget Jones’s Diary, directed by Sharon Maguire to the spate of Jane films in the last decade, since its self-conscious updating of Pride and Prejudice confirms its homage to the franchise by picking up Colin Firth, the Mr Darcy from the much acclaimed British television version of the novel and makes him the Mr (Mark) Darcy here. It’s just a guess, but I’d say that the appeal of Miss Austen to the post-modern era is that she is a feminist heroine—for the clear-eyed intelligence with which she saw the commercial and practical side of love and romance two centuries ago—who nevertheless gives a kind of permission for women to go on seeing the fulfilment of their lives in getting married.

At any rate, the wild popularity of Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary, first serialized in the London Daily Telegraph, seems to depend on the responsive chord it struck among 30ish urban career girls, “singletons” worried about their declining marketability as wives and at the same time obscurely guilty about their worry, as if it were not quite clear to them why it was not worse to disappoint feminist expectations than to remain unmarried. The appeal of the newspaper and novel versions of Bridget lay in the diary format, which promised us a peek into the secret life, the diary life of our heroine where social posturing and political correctness would be left behind and we would see—as, indeed, we did see to a limited extent—the naked feminine desperation that no woman would willingly expose. It was a kind of emotional striptease.

Very little of this survives in the film, which has been given the Four Weddings and a Funeral or Notting Hill treatment by the same team that made those films—producers Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner and screenwriter Richard Curtis (assisted by Miss Fielding and Andrew Davis). Even Hugh Grant is once again on hand, this time in the role of the villain, Bridget’s lecherous boss Daniel Cleaver. The director, Miss Maguire, is a friend of Miss Fielding’s and the basis for a character, Shazza, in the original Diary who oddly makes that character in the movie into little more than a spear carrier. But then when you’ve got a star as big as Renée Zellweger in the title role you don’t want to be lavishing your attention on character parts.

I regret the limited role of Shazza and Bridget’s other pals less than I do that of her parents. Both Gemma Jones and Jim Broadbent are terrific actors whose own little marital drama, involving mum’s midlife crisis and brief stint helping a new boyfriend pitch junk jewelry on the home shopping network, is funny so far as it goes but truncated. This is a pity because in a more prominent position the sub-plot would have provided a bit of counterpoint to the predictable romantic comedy which predictably takes over the story, and something of a commentary on marriage which is otherwise, romantic-comedy-like, pretty much taken for granted here. The nearest we get is the look on Bridget’s face when mum says: “To be honest, darling, children aren’t all they’re cracked up to be. If I had it to do over again, I’m not sure I’d have any.”

Having said all this, however, I must give credit where credit is due. Bridget Jones’s Diary is a frequently-funny movie, and Miss Zellweger is a wonderful Bridget. She bulked up for the role to give her anxiety about her weight some point and does the accent, to my ear anyway, flawlessly. Most importantly, she shows no fear of looking ridiculous, as the script frequently requires her to do, and so reveals a hitherto unsuspected talent as a light comedienne. With this role she goes to the head of her class of actresses of her generation. Hugh Grant is also terrific as the heavy, making him a Grant-like light-heavy who is recognizably the same witty and charming fellow he was in his other Bevan-Fellner-Curtis roles but with just enough of a turn to the dark side. Firth doesn’t have that much to do as Darcy, but he does it manfully as he did before.

Obviously, the proven commercial instincts of the producers must have made it inevitable that this central star-triangle would burn out pretty much everything else in the Bridget story, but given that it does you have to be grateful that it is made as watchable as it is. Even the promise of the diary’s drawing aside of the social veil is given a deft, ironic treatment when Mr Darcy catches a glimpse of his early characterization by Bridget and ends by agreeing with her that “everyone knows diaries are full of crap.” In recognizing that even the most secret feminine thoughts and feelings are generally as much a performance as the rest of life, especially those of an unmarried woman over 30 who doesn’t want to remain unmarried, the movie adds something to the book.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.