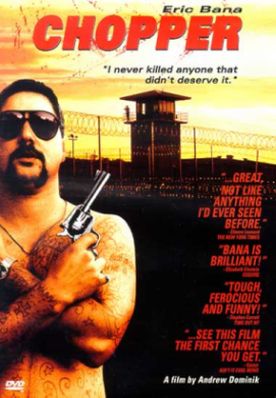

Chopper

Andrew Dominik’s Chopper, which tells the story—more or less—of a true-life Australian criminal-hero called Mark “Chopper” Read (Eric Bana), attempts to make its mark, and to a considerable extent does so, as a fascinating study of raw masculinity. Chopper got his nickname by cutting his own ears off while in prison in order to get out of a maximum security wing where he would certainly have been murdered by enemies. Not that that would have been a very bad thing from any point of view but Chopper’s. But it brought him the sort of notoriety that plays particularly well in Australia, and he seems to have done the rest with a certain roguish wit and a talent for manipulating the media.

The beginning of the film is brilliant, with Bana’s Read talking directly to the camera and showing us what it is that the camera likes about him. He says to an interviewer off-screen that “the average person thinks I’m a bloody freak.”

“What’s your opinion?” asks the interviewer.

“I’m just a normal bloke,” he says, and then, with perfect comic timing, adds: “A normal bloke who likes a bit of torture.”

What a card! But the film—unlike the TV documentary it shows us constant glimpses of as a reminder of the media’s role in making Chopper what he is—isn’t letting him get away with this light-hearted approach to criminal violence (at least not at this point). It then takes us inside a prison where Chopper seems to have some kind of beef with a fellow prisoner called Keithy George (David Field). Chopper’s friend Jimmy (Simon Lyndon) asks him “Why do you hate him?”

“I don’t hate him,” says Chopper.

“Why have we been fighting him for three years then?”

“I don’t know.”

“Maybe we ought to have a reason,” suggests Jimmy, reasonably.

“Well make one up!” says the exasperated Chopper. He can barely understand the concept of fighting for a reason. Fighting is the reason. It is the bedrock reality of his life, both in and out of prison, but what he then does to Keithy and what is done to him in retaliation are things so horrible—and represented as being so horrible—that there is no possibility of the fighting being glamorized or romanticized. What the film does do, however, is show us how Chopper’s violent deeds are committed in a kind of trance-like state from which, at some level, he remains detached. Thus as he watches a man he has stabbed bleed to death in front of him we see the long buried human part of him express anxiety and sorrow as he attempts to reassure the man that he is not going to bleed to death and to offer him a cigarette.

The same detachment reappears when he is on the receiving end of the violence. When his best friend, Jimmy, stabs him several times, Chopper offers no resistance and merely asks: “What are you doing? What’s got into you?”

“Sorry, Chop,” says Jimmy.

“It’s all right,” says Chopper. These things happen. Then Jimmy stabs him again. “Jimmy,” says Chopper with an avuncular concern. “If you keep stabbing me you’re going to kill me.” Later, when he is asked why he didn’t retaliate or seek help, Chopper says that “the bloke’s been my best mate since 1975,” adding: “We’ve had our ups and downs.” Then, searching for an analogy that can best explain what he means he says: “It’s like your mum stabs you. What are you going to do? You’re not going to say—” and here he puts on a whiney, little-girl voice: “‘Ooh, mum stabbed me!’ and go off to the hospital, are you?” Violence to him is a natural part of the “ups and downs” of any loving relationship, as it is in a more predictable way with his girlfriend, Tanya (Kate Beahan).

If the film had left it at this, or gone more deeply into the question of why such a man appeals to a mass audience, at least in Oz, it would have done very well indeed, but at this point it veers off into a bit of glorification of its own, it seems to me. For a time it even appears ready to take the lovable rogue at his own estimation as a kind of quasi-Robin Hood figure, working with the police to clear human scum off the streets of Melbourne. Keithy’s accusation against Chopper, later echoed by Jimmy, that “you bash people for no reason, just to make a name for yourself” could if taken seriously have made him much more interesting than he is as a comically self-deluded crime fighter and media “personality.” Not that this view of him doesn’t occasionally have its points too. I especially liked the scene in which the television interviewer puts a statement as a question, as interviewers will: “You’ve written a best seller.”

“I know!” says Chopper, obviously delighted. “And I can’t even spell!” The idea affords him so much amusement that he even squeezes out a drop of pity, the only one he has, perhaps, for the “poor academics, slogging their guts out” to write books that no one wants to read. “I can’t even spell,” he repeats. “I’m semi-bloody-illiterate. I bet they hate me.” It is the film’s saving grace that it is able to join in the joke.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.