Bring Back the Duel

—from The New Criterion

As is well known, members of Parliaments with rules derived from those of the

mother of Parliaments are forbidden from using the word “liar” or

“lie” to refer to other members or their remarks. You can see why

this rule is a necessary one. The charge that someone is lacking in good faith

poisons the wells of debate in a system which is founded on debate. It invites a

retort in kind which at once drains the system of substance and renders the

parliamentary process trivial. The deliberations of our own dear legislature

have been trivialized and drained of substance for other reasons, however, which

unhappy fact throws most if not all of our substantive political debate into the

press—where charges of lying made by political adversaries against each

other now seem to have become almost routine.

Of course, it is easy to lose one’s head in the heat of political

strife, but what are we to think of those who, with every opportunity for

reflection and the moderation of passion, accuse their political opponents of

lying in cold print—which affords slanderers and calumniators a certain

amount of protection? But then, the words “lying,” “lie”

and “liar” nowadays hardly seem to carry the kick they did in the

days when violence was likely to accompany their deployment. Partly this must be

as a result of the crudeness and vulgarity of the media culture that I discussed

in this space last month. Every time someone—like, say, Gary

Condit—is unresponsive to press inquiries about the most intimate details

of his private life he is accused of “lying.”

As I argued then, it is nonsense for the media to pretend that any public man

who does not open up his private life to the scrutiny of any idle

curiosity-seeker is a liar. But so far have we accepted media values that

someone like Representative Condit does not even have the spirit to resent the

slander. Hence the ridiculous spectacle of his offering his throat to the media

hounds on nationwide TV and then refusing to answer their questions, as

charmingly put to him by Miss Connie Chung. Naturally, he was torn to pieces.

Why did he submit to such an interview unless he had already acquiesced in the

right of the media to know all there was to know about him? And having accepted

that he had forfeited his “zone of privacy”, where did he think he

was going to get the standing to reassert it on the air? What he may or may not

have got up to with Chandra Levy will probably never be known, but it is beyond

dispute that he hadn’t the wit or the courage or the self-possession to

defend his own honor in public. I wonder how many of our congressmen and

senators would have had these qualities in his position?

You don’t have to wish for a return to dueling to recognize that, if

the accusation of bad faith is not vigorously–though perhaps not always

violently—resented, it will be made more and more often. Another reason

for this sad state of affairs must be the extent to which politics in general

has become trivialized during the Clinton years. The Carville-Matalin Punch and

Judy show —now happily out of sight while Miss Matalin is serving in the

administration—stressed the extent to which neither the elder George Bush

nor Bill Clinton nor their many spokesmen really meant what they said anyway.

Hadn’t Bush, after all, broken his promise not to raise taxes after having

made it the centerpiece of his electoral appeal in 1988? Didn’t Clinton

say on national television: “I did not have sex with that woman”?

Naturally enough, when lying itself becomes standard operating procedure, so

will the accusation of lying.

Though politicians themselves, who still have to meet each other every day,

may still be relatively shy of it, there is no evident journalistic inhibition

against promiscuous accusations of knowing falsehood being brought against

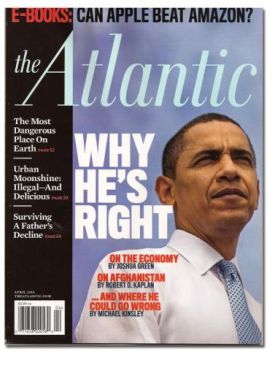

one’s political opponents. Last May The New Republic, still

editorially grumpy because Al Gore wasn’t president, ran a cover with a

picture of George W. Bush and the loud headline: “He’s Lying.”

What he was allegedly lying about, said Paul Krugman and Jonathan Chait inside,

was budget projections made for ten years to come which purported to show that

there would be, given the projections’ assumptions about economic growth,

plenty of surplus tax dollars coming into the Treasury to “pay for”

the Bush tax cuts, then being debated (and subsequently passed) in Congress.

If The New Republic had confined itself to observing that the

Administration’s projecting the amount of tax receipts to the Treasury in

2011 was a laughably inexact exercise, there could have been no objection. But

Krugman, a professor of economics at Princeton and columnist for the New York

Times insisted that “The fiscal predictions that enable Bush to pay

for his tax cut and contingency fund are not mere errors but deliberate efforts

to deceive the public.” Harsh words! That, presumably, is the sort of

intellectual street-fighting they engage in at Princeton, where passions

obviously run higher than they do in Washington. Professor Krugman proceeds to

demonstrate what would be the fiscally terrifying result of having made the same

projections “with proper accounting,” but for the charge of bad

faith made against the President of the United States he offers no evidence

beyond the fact that he doesn’t agree with Professor Krugman.

Likewise, Mr Chait, a senior editor of the magazine, notes that “the

debate over the Bush tax cut has been shrouded in a fog of cant and

untruth”—all of it, presumably, emanating from one side. Unlike

Professor Krugman, however, he has what he considers to be evidence of

prevarication and not just bad economics. It is this. In a leaked memo from the

Republican leadership in Congress which sought supporters for the tax cut for a

televised rally, he found the following: “[T]he Speaker’s office was very

clear in saying that they do not need people in suits. If people want to

participate —AND WE DO NEED BODIES — they must be DRESSED DOWN,

appear to be REAL WORKER types, etc. We plan to have hard hats for people to

wear. Other groups are providing waiters/waitresses, and other types of

workers.”

QED! “If the advocates of the Bush tax cut were honest, a memo like

this would not exist,” he solemnly informed his readers. By this standard

of honesty, the former vice president must be branded a liar for combing over

his bald spot. But his doughty partisans at The New Republic, no longer

in any danger of being called to the field of honor to defend their calumnies

with their lives, must think that such pathetic scrounging of material for

character-assassination all just part of the cut-and-thrust of political debate

in the post-modern era. In the rest of his piece, Mr. Chait is full of

information about what the Republicans must “really” intend by such

obviously misguided policy prescriptions, but his quiver of proofs that their

“lies” are deliberate and culpable is otherwise empty.

Shocking as the charge that the President was lying may once have been,

The New Republic’s sensational discovery produced little reaction

from the rest of the press. It might almost seem that, in the era of

news-as-entertainment, the public just doesn’t care if its elected

officials are trustworthy or not? Perhaps, those ordinary “workers”

that the Republican fat cats so wickedly impersonated have at last come to

accept what those who move in the most exclusive post-modern circles have been

telling us for a long time, namely that “truth” is a chimera anyway.

That, at least, is one way of explaining to ourselves the late summer saga (or

farce) of the appropriately named “trust funds” belonging to social

security and Medicare.

They are appropriately named because they require trust to believe in them,

though they do not in fact exist by most definitions of what a trust fund is.

They are not, that is an income-producing account consisting of stocks, bonds or

interest-bearing deposits, or some combination of all three. The alleged social

security trust fund is simply the current account receipts from the FICA tax out

of which current social security benefits may, if you choose to look at it in

this way, be paid. It is a strictly notional “fund” because there is

no practical difference between the receipts of the social security tax and

general tax revenues. As a collaborative exercise in demagoguery Republicans and

Democrats got together at the beginning of the era of budget surpluses to

require that the social security tax receipts should be regarded as if

they were in a “lock box” from which those notional wads of cash

could only be taken in order to pay social security benefits and nothing

else.

How this would help either social security beneficiaries or the fiscal health

of the nation must be supposed to have been as obscure to the framers of this

foolish statute as to everybody else, but what it certainly did was to create a

kind of suicide pact of the two parties, an agreement by Republicans to allow a

portion of tax revenues to be held hostage rather than being given back in tax

relief and by Democrats to restrain spending, lest either side open itself to

the charge of robbing the elderly and infirm—a charge which, though

acknowledged by everyone to be untrue, is equally acknowledged to be

unanswerable and politically fatal. The press, plays along with the same charade

because it adds to the thrill of political combat that such a super-weapon may

be employed at any moment.

In the meantime, we must make do with that rusty old dueling pistol, the

lately trivial charge of bad faith. And whom should we find deploying it most

assiduously from his perch on the op ed page of the New York Times but

our passionate friend, Professor Krugman, sounding even more than the other

Times columnists as if he were on salary from the DNC. Again and again he

could be found over the course of the summer firing at the Republicans charges

of immorality that Dick Gephardt or Tom Daschle would blush to make. In a column

of August 24 headed “Pants on Fire,” for example, he pretends to

write an open letter to Mitch Daniels, the head of the Office of Management and

Budget:

Dear Mitch:

I have a

suggestion. It’s dishonest and irresponsible — but I suspect that doesn’t

bother you. And it would help you squirm out of a problem that we both know

isn’t going away.

True, your bobbing

and weaving have been impressive. Some people have actually bought your line

that the surplus has vanished because of Congressional big spending. . .But

there’s more trouble ahead. You bullied the Congressional Budget Office into

delaying its own budget projection until next week, so that you could get your

numbers out first. Still, when the C.B.O. numbers come out everyone knows that

they will look considerably worse than yours.

And of course we

both know that the truth is actually even worse than that, because the C.B.O.

must pretend to believe what politicians tell it.

He goes on to make a tongue-in-cheek suggestion that Daniels announce that

the defense budget is part of Social Security–which, he says is

“just an expanded version of your administration’s Medicare scam.”

As a witness he calls an I.M.F. report which said, “basically,” he

avers, “liar, liar, pants on fire” to the Bush budget numbers. On

his own responsibility he refers to “blatantly dishonest

accounting,” designed to provide “big tax cuts to the very, very

affluent.” This is a view that he continually repeats for several columns

on the same subject, frequently adding along the way snide attempts at irony

that look as if they were intended to be subtle but somehow went horribly

wrong—like “Let me pretend for a moment that the truth

matters” or “Dishonesty in the pursuit of tax cuts is no vice. That,

in the end, will be the only way to defend George W. Bush’s deceptions.”

In another column, he writes:

After all, a

recent study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that the

revenue lost because of the Bush tax cut will be more than twice the sum needed

to secure Social Security without any reform at all for the next 75 years. The

administration tried to refute that calculation, playing its usual game of

statistical three-card monte — “Look, honey, I just found $4 billion under

the cushion, and 60 lines of stem cells too!” — but the center’s estimate

matches those of the I.M.F. and other independent organizations.

I don’t know much about card-swindles, but I don’t believe that

three-card monte consists of lifting up seat cushions and finding things that

aren’t there. What, exactly, was then this bit of dishonesty he says was

involved in the administration’s attempt to “refute” the

Democratic think tank’s calculation of the effects of the tax cut? Krugman

doesn’t say, expecting us to take the charge on faith—his own (good)

rather than Bush’s (bad). This is odd coming from a man who elsewhere

asserts that the charge of lying brought against the President was “a

simple statement of fact.” Admittedly, from that quarter such a charge is

hardly remarkable, but the point is that it should be. An accusation of

dishonesty is not something to be made lightly, or without factual (rather than

interpretative) documentation in support of it.

It’s not even as if both honesty and temperance of language are that

difficult in this case. There are good arguments to be made on each side, and a

genuinely–that is to say honestly–objective commentator could make

them without having recourse to any bad or dishonest ones. But the central truth

is that the Mexican stand-off over the “lockbox” is itself a piece

of dishonesty–and, apparently, an unassailable one–whose

enshrinement in the center of the political process requires both sides to flirt

with complementary dishonesties. The Democrats blame the threat to the surplus

on Bush’s “tax cuts for the rich,” though as they know that

rescinding the tax cut would be divisive within the Democratic caucus and

unpopular with the public, they don’t propose it. Better to get the

political advantage from abusing a measure without incurring the political

disadvantage of actually doing anything about it.

Bush attempts to play the economic Keynesian, arguing for the stimulative

properties of the tax cut, but only when it suits him to be one. His answer to

the Democrats’ charge of having “lost” the surplus with his

tax cuts is to argue forcefully in reply that the “real” threat to

the economy is not the tax cut but excessive Democratic spending and he actually

welcomes the diminishment or even disappearance of the surplus as a means of

keeping a check on spending. Meanwhile, he joins in the game of making a

shibboleth of the surplus which is, in Keynesian terms, sheer madness and one of

the mistakes that deepened the Great Depression. A government surplus represents

money taken out of the economy at a time when monetary loosening to stimulate

growth is the order of the day everywhere else.

None of this is exactly dishonest. Whether you regard the threat to the

lockbox as issuing from tax cuts or from spending is all in how you look at it.

It is the idea of the lockbox itself as anything other than a means of buying up

government debt which is dishonest. But, as Alan Reynolds put it in National

Review Online “it certainly does not matter whether bondholders are

paid off with excess payroll or excess income taxes.” It may be good that,

in a time of surplus, government debt should be bought up, but no one would

suppose that the surplus should be preserved artificially for that purpose, even

at the cost of a fiscal tightening in the teeth of a threatened recession, if it

weren’t for the false metaphor of the lockbox and the political uses to

which both sides think they can put it.

But this is a very special kind of dishonesty—one that became

particularly popular in the Clinton years when the media’s tacit

acceptance of the dissevering of rhetoric from action was confirmed with its

failure to protest against the obvious humbug of Clinton’s assurance that

he could “feel your pain.” Accept that and you can go on to accept

that Clinton himself believed that he was telling the truth when he said he had

not had sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky. From there it is easy to accept

without comment the Democrats’ charge that the administration was not

“protecting our seniors”—as if anything less than a $160 billion surplus

would result in decreased social security or Medicare benefits to current

recipients, whose benefit levels are mandated by law.

All this is sheer demagoguery of course, but it is now the custom of the

country. On the Republican side, the demagoguery is also a form of

self-contradiction. It is not necessarily, or not culpably, self-contradictory

to argue that the fiscal stimulus of tax-cutting will produce more benefits than

the fiscal stimulus of increasing spending, but Bush does not make that

argument, instead hoping (presumably) that the contradiction will be too

difficult for ordinary folk to understand anyway. He may well be right, but if

so he counsels despair. Clinton’s treatment of the political debate was

always completely cynical, and he never made much effort to raise the

intellectual level of his political rhetoric to the point of coherence (remember

that “bridge to the 21st century”?), perhaps calculating

(surely rightly) that he had the intellectuals in his corner anyway.

Bush the younger, in attempting to emulate his predecessor can obviously not

rely on the acquiescence of the professoriat. Determined not to make the mistake

of his father—or at least the mistake his father made of being

out-humbugged in 1992 — he has tacitly accepted what was already de facto

reality among the Democrats and the media, namely that real, serious political

debate in this country is no more. Thus the media swallowed without a peep the

“arsenic in drinking water” charge by the Democrats, though they

knew that it was another bit of shameless demagoguery. They certainly

wouldn’t want to appear “biased” by pointing the fact out, yet

not to point it out could hardly be consistent with honesty, at least as honesty

has traditionally been understood.

The habit of impugning one’s political opponent’s good faith was

perhaps made easier by the habit on the left, which is now even more common

among the apolitical but bien pensant who describe themselves as

“moderates,” of impugning the “compassion” of fiscal

conservatives because of their tendency to be less generous with other

people’s money, if not with their own. Now fiscal conservatism, since the

Clinton era, has been somewhat rehabilitated. But the “compassion”

of social conservatives — for example, on behalf of homosexual partners

who are not allowed to marry each other — is still freely questioned, and

few non-conservative voices are ever raised in protest. Of course it

didn’t help that George W. Bush saw this calumny as an opportunity to

advertise himself as a “compassionate conservative”— as if

admitting the charge made against the conservatives before him.

But there is a difference even between this insult and one of dishonesty. In

fact, the worst humbugs are the most honest: they really believe that they feel

the pain of the unfortunate, and that this gives them a better claim to knowing

what to do on their behalf. Arguably, it is even fair fighting for liberals to

call conservatives uncompassionate, just as it is for conservatives to call

liberals profligate, though both would presumably deny the charge. But it can

never be fair to accuse someone of dishonesty unless the purpose of doing so is

to have him expelled from the fora of civilized discourse. But then, that may

well be what the likes of Paul Krugman want to happen to conservatives.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.