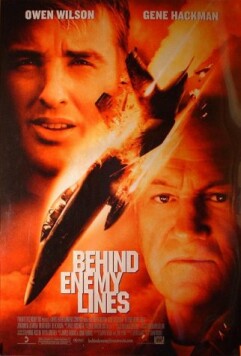

Behind Enemy Lines

Owen Wilson has a nose like a bottleneck. It positively has a waist in the

middle. This makes him a natural, I would have thought, for comedy, and hitherto

he has mostly appeared in comic roles, including his first major one, in Wes

Anderson’s Bottle Rocket, and the Jackie Chan vehicle, Shanghai

Noon. In his new picture, Behind Enemy Lines, directed by John Moore,

he plays it serious as Lt. Chris “Longhorne” Burnett, a naval

aviator and navigator on an F/A-18 Superhornet who is shot down over Bosnia because, on

a reconnaissance run, his plane took photos of a mass grave he was not supposed

to have seen. The bad guys are (naturally) Serbs, and they execute his pilot

(Gabriel Macht) while, having safely ejected from the burning plane, Burnett is

off in search of higher ground from which to radio for help.

When he gets in touch with the U.S.S. Carl Vinson, Admiral Leslie Reigert

(Gene Hackman), the commander of the Vinson battle group, orders a rescue party

to go pick him up but he is prevented from sending it by his NATO superior,

Admiral Piquet (Joaquim de Almeida). Admiral Reigert — who has recently

been shown dressing down Burnett for the latter’s impatience with the U.S.

mission (“I signed up to be a fighter pilot, not a cop, and especially not

a cop in a neighborhood nobody cares about”) — tells him to act like

a naval aviator and evade capture, but it is made clear to us that he, as well

as the whole of the ship under his command, shares Burnett’s dislike of

the bureaucratic restrictions that the NATO diplomatic structure and the

“fragile” treaty that the politicians have negotiated with the

Bosnian Serbs impose on them.

Here is really the weakness of the film. We can understand the impatience of

gung ho warriors with diplomatic niceties, especially when one of their own is

in trouble. But the film is not content to leave it at that. Like so many other

Hollywood movies of the recent past, it doesn’t consider its treatment of

politics complete without at least an implicit conspiracy theory. It is

therefore suggested, without being spelled out, that Piquet — oh those

perfidious French! — is in cahoots with the Serbian war criminals and

therefore deliberately interfering with the Vinson’s attempted rescue of

Lt. Burnett. All that stuff about fragile treaties is just a convenient excuse.

Piquet even seems to have Admiral Reigert’s American superiors in his

pocket, though it is not made clear if they are in on the plot.

This is another example of Hollywood’s dumbing down a movie with a

serious theme so that morons and pre-teens can understand it. They looked at the

real-life story of Lt. Scott O’Grady and decided it wasn’t exciting

enough. We’ve got to have it spelled out for us in more familiar terms who

the good guys and the bad guys are and, as always, the former are the soldiers

on the ground and the latter are their superior officers. But sometimes, in the

grown up world, treaties really are fragile and coalition partners really do

have to be placated for really good reasons. Wouldn’t it be more

interesting to see a movie with some real moral, political and military dilemmas

in it? Isn’t it getting a little tiresome even to the people who make

these films to go on treating with such monotonous regularity the U.S. military

and diplomatic authorities as fools or knaves against which the ordinary

soldiers engaged with the enemy must invariably rebel in the pursuit of good and

noble causes? Apparently not.

Having said all that, let me say what is good about the movie. It is

pro-American, pro-military (below the highest echelons, of course) and rather

excitingly photographed. I could have done without the loud bangs on the

soundtrack to accompany significant moments in the action and the photographic

gimmickry of stop action and fast forward, which are also (I think) a kind of

dumbing down. In spite of these, however, the action sequences are quite often

thrilling, especially those involving aerial photography — which seems

more natural and at home in the movies than the scenes of ground combat, which

are by contrast occasionally too “movieish.”

I particularly liked the idea (though it seemed rather improbable) of having

a heat-imaging satellite photo (even watching this in the Vinson’s

communications center “isn’t strictly legal” it is said, since doing

anything good in Hollywood invariably means breaking the rules) as the Serb

killers are seen closing in on Lt. Burnett. We see the heat shadow of the

Lieutenant in a prone position and we see the upright heat shadows of the Serb

detachment approach and then surround it, and yet they seem to mill about,

unable to find him. The watchers on the aircraft carrier, expecting the imminent

death of their comrade, cannot understand what they are seeing, but we are

transported, through the magic of the movies, to the scene on the ground where

we are allowed to see Burnett hiding under one of the bodies in the mass grave

and the Serbs, repulsed by their own handiwork, moving on after bayonetting a

few corpses.

In other words, the film is a political and diplomatic mess. It makes no

sense and only looks like the Hollywood cliché it is for making American

soldiers always and forever at war with their own superior officers before they

are at war with the enemy. But when Reigert defies his orders and goes to rescue

Burnett anyway in the teeth of what looks like a Serb armored brigade, you will

have a hard time coming away from the spectacle without a lump in your throat as

big as the nose on Owen Wilson’s face.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.