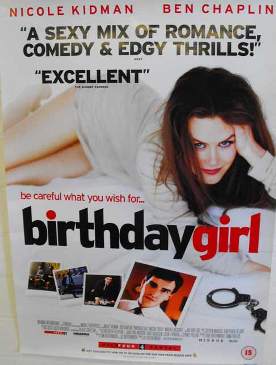

Birthday Girl

Birthday Girl, directed by a young English person calling himself Jez Butterworth and written by him and his brother, Tom, shows us something of how “the American dream” has lately become the British — or the French or the German or the Australian — dream for would-be immigrants desperate to get out of the second or third worlds and into the first. Unfortunately, the Butterworths turn out not to be very much interested in the subject once they have tapped into the ironic potential of having the tables turned on would-be Western exploiters of poor Russian girls seeking to sell themselves to foreigners as mail-order brides. John Buckingham (Ben Chaplin), a lonely and mild-mannered bank clerk from St Albans with a taste for pornography, orders up the beautiful Nadia (Nicole Kidman), but she comes along with a couple of Russian con-men, Alexei (Vincent Cassel) and Yuri (Mathieu Kassovitz), who force him to steal £90,000 from his bank for them.

It is an interesting scenario, but the words “mail-order bride” seem to have made the Butterworths melt. All they could think of to do with the story was to make it a romance. Now you can just about get away with telling the story of the mail-order bride who turns out to be her purchaser’s one true love, but for all the charm and the wit of the story as they tell it, we can’t help noticing that it is stretched out of all resemblance to reality. What were they thinking when they made the bride a con artist and associate of thugs, a willing participant in a scheme to force a young bank clerk to rob his employer in the mistaken belief that he is protecting her, and then made her turn out to be his true love? Didn’t the Butterworths run this preposterous scenario past anybody for a plausibility check? The depressing thing is that they probably did but that nobody much minded the absurdity. Moreover, when John does a Patty Hearst and takes Nadia, now shed of the thugs, and the money on the lam, they go back to Russia!

Of course, £90,000 will go a long way there, but is there no sense of the moral cost? I know that it has become almost a commonplace of the contemporary cinema to represent thieves and crooks of all kinds as, really, just people like ourselves, people who long to be loved and who only want (as they invariably say they want) just the one big score before settling down to a decent suburban domestic life just like anybody else. That’s why nowadays it is almost as routine for the crook to get away with the swag in the final reel as it once was for him (or her) to get put in jail or killed or both. The people who were honest, decent suburban family types all along and who have to take the loss (usually only in the form of higher insurance premiums) can well afford it, after all. But as we gradually acclimate ourselves to seeing criminality as the norm, the very ideas of honesty and decency must begin to recede.

As it is pointed out to us in this film “banking asks a great deal of an individual. It says: here’s all this money and, and. . . Don’t steal it.” That’s putting it in a nutshell. But who would have thought until recently that that was asking “a great deal”? Likewise, the idea of the mail-order bride has been used to comic effect of men on the frontier, but for someone living among the sexual plenty of contemporary London and vicinity? People do still, of course, go for mail order brides, but they do so (one supposes) in the hope of getting simple country girls grateful for the leg up (and over) to prosperity who will be easier for their husbands to master and control than those native-born gals whose expectations have been formed by feminism. This aspect of John’s purpose in sending in his order for Nadia is left almost completely unexplored.

There is one moment of truth, at least. John, rather tauntingly, asks Nadia: “Did you think you would end up flat busted, bun in the oven, on an Aeroflot back to Moscow?”

Nadia shoots back: “Did you think that you would be in same house, in job you hated with big bag of pornography and say: I will send to Russia for bride and she will love me. What did you expect, John?”

But once that moment of clear-sightedness is got out of the way, they fall into one another’s arms. She does love him! Well, that’s what the audience wants to see, I guess. There is probably focus-group evidence to prove it. And the Butterworths, though they are obviously witty, talented and clever film-makers, have their way to make in the world as well.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.