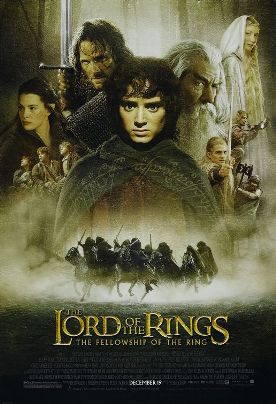

Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring

Readers as attentive as mine will doubtless have observed already that I have for some time been trying to avoid writing about the first installment of Peter Jackson’s massive, three-part film adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. Of course there were lots of opportunities not to write about it with the rush of studio showcase movies and Oscar contenders that came out at the end of the year. But I confess that the real reason I was turning my attention elsewhere was that I had found the movie rather dull and was feeling obscurely guilty about the fact. So many people have written in asking for my take on it and obviously expecting a good one that I was reluctant to disappoint them. What can I say? I believe that it is morally and philosophically sound and teaches our children a good lesson about heroism and virtue and honor. Will that do?

Probably not. Although at times I think that I am just getting too old to take delight in fantastical creatures like hobbits and elves and orcs and dwarfs, long-time readers will know that I have never been keen on fantasy. It is true that, when I was quite a young man I read the Tolkien books with pleasure, but now I find myself sympathizing whole-heartedly with C.S. Lewis’s (perhaps apocryphal) comment on the occasion of one of Tolkien’s readings before a gathering of the Inklings at Oxford during the war: “Not another f***ing elf!” Thus I find myself torn between intellectual admiration and aesthetic doubt, between moral acquiescence in what amounts to a celebration of a very old-fashioned kind of heroism and the film-critic’s lust for something new and exciting which (it has to be said) remains largely unsatisfied.

In other words, it is not only my age that makes this movie less impressive than it might otherwise have been, it is the age of the world and the age of the movie culture we live in. Most if not all of the special effects have been seen before. Peter Jackson’s attempt to translate the wilder flights of Tolkien’s fancy into visual imagery are often clever and well-managed but they do not strike us with the force of revelation. And some things — I think particularly of the depiction of the orcs whose almost stylized hideousness is of a very familiar but a very cinematic kind — seem positively hackneyed.

Nor is it only the cinematic world to which this movie comes belatedly. Perhaps a war fought with swords and arrows would have looked more compelling before September 11th, but somehow in an environment rife with accounts of daisy-cutters and bunker-busters and al Qa’eda fighters in headlong flight from Tora Bora — Afghanistan, like Middle Earth, being a place packed with evocative names — even the Mines of Moria or the forge of Mt Doom lose some of their fearsome impressiveness. The metaphor of the ring of power, which corrupts all those who use it, is a venerable and an evocative one, but it comes at a bad time for us. It seems that we’ve heard far too much and for far too long about the corruption to which those who wield power are uniquely susceptible. Yeah, well. Now it’s time to kick some ass.

It is no discredit to Peter Jackson to say that it is his very faithfulness to Tolkien’s text — and we have testimony to such faithfulness by no less an authority than Professor Tom Shippey, his fellow Anglo-Saxonist and, in J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, his chief advocate — which makes his movie more of a curiosity, almost an exercise in nostalgia, than a landmark of the cinema. I was particularly struck, for example, by the movie’s representation of the faithfulness of Sam Gamgee (Sean Astin) to Frodo (Elijah Wood). The climax of part one (parts two and three, shot at the same time, will be released over the next two years) is not so much Frodo’s going off on his quest alone as it is Sam’s insistence in coming along. “I made a promise, Mr. Frodo. ‘Don’t you lose him, Samwise Gamgee’,” says Sam, quoting Gandalf’s final injunction to him. “And I don’t mean to.”

Now Sam is not meant to be seen as a hero in his own right but the servant of a hero. Even his use of the honorific “Mr. Frodo” has the sound of anachronism about it. He has the comic nature of Shakespeare’s servants, but a faithfulness that from the perspective of the 21st century looks more like the wishful thinking of the British upper-middle classes between the wars than anything occurring in nature. A useful corrective to this movie would be to go see Robert Altman’s Gosford Park — which, indeed, is good for almost nothing else. I would like to think that I am wrong about this, and that the idea of the “good and faithful servant” is something ready for a comeback. But a century of hardboiled posings of Lenin’s question — Who/whom? — is not so easily overcome. In any case, the faithful and deferential servant is now so strange and outlandish a creature that his appearance in this context calls too much attention to itself and unbalances the real point of the movie, which like the book is to represent for us the highest forms of honorable and noble behavior.

Interestingly, the film is also faithful to the physical diversity of Tolkien’s world: the hobbits (or “halflings”) are meant to be about four feet high while, through the magic of the silver screen, Ian McKellan’s Gandalf seems to be at least an eight-footer and towers over everyone. Jackson sees the extent to which Tolkien, very much out of the spirit of his time and ours, was celebrating human inequality in all kinds of ways, though he had to do it by inventing a number of non-human but intelligent species as metaphors. As a result of this, and the emphasis on the heroism even of the lowliest (“Even the smallest person can change the course of the future”), the moral universe of the film, like that of the book, is immensely sympathetic. But that is not enough to make it cinematically compelling, I’m afraid.

Not that there are not a great many other things to like about the movie. Almost equally shocking, if not quite so unbalancing as its celebrations of inequality and faithful servitude, is its advocacy of tobacco. Or are we to take seriously the opinion of wicked Saruman, expressed to the constantly puffing Gandalf, that “Your love of the halflings’ leaf has weakened your mind”? The tobacco, the beer, the hearty eating of the hobbits — “I don’t think he knows about second breakfast” worry the hobbits about their human leader, Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) — all insist on the Englishness of the shire and its earthy, working-class pleasures. But much as I approve of all these things, I find them far more literary than cinematic. Movies cannot do justice to the other senses in the way that books can because they are so overwhelmingly present to the eyes and ears.

What are we to make of this defiant Englishness in the age of European homogenization? I myself am a strong advocate of the English remaining English and not becoming European, but I am doubtful that this is anything but nostalgic whimsy on my part. The shire is now gone in a way that neither Hitler nor the legions of Saruman could ever have accomplished. There is a kind of allegory in the thing, perhaps. For if the heart of it is that “The time of the elves is over…. It is in men we must put our hope,” it is possible to read Englishmen for “elves” and American technology for “men”? But that way madness lies — the way of those who would make of the trilogy an elaborate political allegory with the ring as The Bomb.

In the end, I conclude that the movie is worth seeing as a kind of cinematic equivalent of one of those rambling heroic epics that have little structure or internal cohesion — though this has both — but that still manage to stir our souls at the moments of stark confrontation with a heroic imperative. So when Frodo wishes that the burden of being the ring bearer had never fallen on him, Gandalf replies as only a god or a very great wizard could: “So do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All you have to decide is what to do with the time that is given to you.” Even in the movies, with their endless appetite for novelty, there is sometimes room for the things that never get old.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.