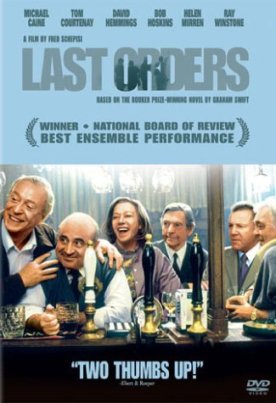

Last Orders

Last Orders, adapted from Graham Swift’s novel by Fred Schepisi, is an actor’s movie but one which also manages to give us a lovely, deeply affecting portrait of ordinary people in the vanishing cockney subculture of East London. I sometimes wished that Schepisi had given just a little more attention to the theme of the ending of a way of life. The historical context is already there, with flashbacks to the war years and even the pre- war years, with the emigration of one character’s daughter and the refusal of another’s son to go into the family business — which is failing in any case. More could have been done to fill in the details. The fact that you see only one or two black faces in the background here and there suggests that maybe Schepisi was being careful lest he be accused of attributing the decline of the white cockney culture to the immigration which had made the East End of London, even at the time the film is set, in 1989, predominantly West Indian and East Asian.

But, as I have often had occasion to say before, the first rule of criticism is never to criticize anything for what it isn’t, only for what it is. And what Last Orders is is a series of interlocking character studies, nearly all of which are successful, and a plot that only emerges as deep background from their youth to the portraits of the main characters in age. The story in the present is almost negligible. Four men drive from London to Margate, in Kent, one day to throw the ashes of a fifth in the sea, in accordance with his dying wishes. On the way they stop for lunch, then at a hop-field, at the Chatham war memorial and at Canterbury cathedral. Finally, they throw the ashes into the sea according to plan.

But their desultory conversation during the drive sets off a series of flashbacks which tells in disjointed but comprehensible fashion the story of the long friendship of the four older men — Jack (Michael Caine), Vic (Tom Courtenay), Ray (Bob Hoskins) and Lenny (David Hemmings) — and their often difficult relations with wives and children, including Vince (Ray Winstone), adopted son of the deceased, Jack, who drives the three older men to Kent in a shiny new Mercedes from his successful car dealership. Vince’s relative good fortune is a bit of a sore spot with the other three, as indeed it had been with Jack, whom Vince had refused to join in the butcher-shop — Dodds and Son — that he had inherited from his father. In addition, a failed romance between Vince and Lenny’s daughter, Sally, and an illegitimate child makes Lenny more or less overtly hostile to Vince all through the journey.

Along the way we also learn from the flashbacks of the courtship of young Jack (J.J. Feild) and his wife, Amy (Kelly Reilly) when both spent pre-war summers hop-picking in Kent and going to Margate pier for recreation, about Jack’s army service in the desert and Egypt during the war, where he met young Ray (Anatol Yusef), about Vic’s service in the Navy, Ray’s marriage which broke up after his daughter emigrated to Australia and the romance between Vince and Sally when the latter had been taken with Jack and Amy on family holidays to the beach. Through all these other stories runs the thread of connection represented by the unhealed wound in the marriage of Jack and Amy: a severely retarded daughter called June (Laura Morelli), whom Jack would never speak of but whom Amy, played in her later years by Helen Mirren, visited in the institution where she had been warehoused every Thursday for fifty years — even though June never gave a sign of even knowing who she was.

Or rather, every Thursday save six one summer in the late 1960s when Amy had been driven by Ray in his camper, instead of going by bus as usual, and had had a brief affair with him instead of visiting June. Jack never found out, and Amy always insisted that he really did love her, even though he didn’t love June. Finally, while on his deathbed, Jack had confided in Ray, an inveterate player of the horses, that he had only managed to save his butcher-shop by taking out a loan from some loan shark, on which he now owed £20,000. He had borrowed £1000 from Vince and asked Ray to put it on a long-shot, so that he could win enough to “see Amy right” after he is dead. Ray reluctantly agrees and is himself surprised when Fancy Free comes home at 33-1 to make sure that Amy is, indeed, seen right. The film ends with the suggestion that the now well-provided-for widow and Ray may together travel to Australia to find his daughter, with whom he has lost touch, and possibly some grandchildren.

It all sounds rather soap-operaish, I know, but it is saved from banality by the fine performances of the principal actors and by the well-judged elegiac tone. I have often before had occasion to point to the way in which the movies are a sort of national photo album, since one thing they do superbly well is recreate the sights and sounds and textures of life in former times and so prod our memories. At worst this becomes a mere wallow in nostalgia, but at best, as in Last Orders, it offers a true account of time’s passing, and of the stages of life, in a way that no other art form can do. The happiness and the disappointment of life in both youth and age are depicted with loving care, and we are left with a sense of lives lived with greater or lesser skill and luck and wisdom but well and truly lived nonetheless. By the time that his son and his three best friends (but not his wife or daughter) say good-bye to Jack in a driving English rainstorm at Margate, we know him too, and feel the pain of the farewell.

Undoubtedly part of the emotion which the film generates is owing to the presence of the past in the Chatham war memorial and Canterbury Cathedral and even the hop-field and the cheap amusements of the Margate pier. The sense of the long and storied history of Britain constantly in the background (“That’s where Becket got done, up there on them steps”) suggests some sense in which this, too, is coming to an end with the lives of the four old friends. Perhaps, on reflection, I am just as glad that Schepisi did not insist on this idea or emphasize it unduly but let it remain only a sort of echo of the long goodbye to Jack. If the parallel had been spelled out, it would not have been true. As it is, it is just enough to intensify our feeling of loss and regret but not enough to imply any unfortunate demographic or social animadversions.

Working class culture like that of Jack and Ray and Lenny and Vic is coming to an end all over the Western world — as, of course, is upper-class culture. The vast vulgar middle that survives and thrives is scarcely deserving of the name of culture at all. Its culture is in how a particular society copes with its limitations — including the ultimate limitation of death. But we live in a society which insists that limitations are only there to be overcome. Even death will be overcome, it is vaguely supposed, when we have learned how to grow our own spare parts with the black arts of cloning and genetic engineering. It is the nostalgia for a time when people understood and accepted and coped, however badly, with their common limitations that Last Orders is particularly good at evoking.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.