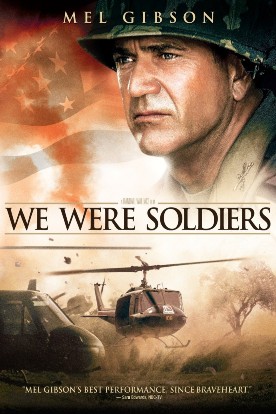

We Were Soldiers

Right at the end of We Were Soldiers, Randall Wallace’s film adaptation of General Harold Moore’s book (written with Joe Galloway) We Were Soldiers Once, and Young, the anonymous North Vietnamese commander visits the now-deserted site where a battalion of American Air Cavalry has just fought its way out of an ambush at Landing Zone X-ray in South Vietnam in November, 1965 — an ambush in which the Americans and their leader, the then Colonel Moore (Mel Gibson), were outnumbered at least six to one by NVA regular troops. “Such a tragedy,” says the North Vietnamese commander in front of a head-high pile of the bodies of his own men. “They” — meaning we — “will think this is their victory, so this will become an American war. The end will be the same,” he concludes — by which we are meant to suppose that he remains confident of the ultimate Communist victory. But, this humanitarian adds, “the numbers who will die before we get there” will be much greater.

What it is to be wise after the event! The man who had done his best to kill all those Americans was apparently right in saying that it would have been better if he had succeeded, since a successful massacre might have induced the Americans — like the French before them, according to the movie’s account of it — to pack up and go home, saving many lives on both sides. This is a foolish concession that the film makes to the current pop and journalistic consensus about the war, which is that it was at best a mistake and at worst a crime and should never have been fought. The good news is that that is its only concession of this kind. Otherwise it owes nothing to the tradition of Vietnam War movies of the seventies and eighties in which American soldiers were almost invariably depicted as undisciplined, drug-addled, trigger-happy cowboys completely without a clue as to what they were doing in Vietnam and so sinking slowly into a morass of madness and senseless slaughter.

Here, by contrast, the Americans are fine, intelligent, brave and noble warriors straight out of the Hollywood World War II tradition. It is as if the newer traditions of the last thirty years of movie-making had been simply wiped out. It could hardly be more shocking if we were to see a new movie of Custer’s Last Stand in which the boys in blue were once again the heroes and the Indians the villains. Perhaps recognizing this, We Were Soldiers plays with the story of Custer — in a slightly post-modern way and without exactly taking sides — since there is a natural connection in the fact that Colonel Moore’s Air Cavalry unit is given the same designation as Custer’s: Seventh Cavalry, first battalion. Col. Moore is haunted by the story, with which the film begins, of the massacre of a French unit by Viet Minh forces a dozen years before and naturally thinks of Custer as well. At one point when their prospects in the battle look bleakest he asks the outspoken Sergeant-Major Plumley (Sam Elliott) what he thinks “was going through Custer’s mind when he realized he’d led his men into a slaughter.”

“Sir, Custer was a pussy,” says the Sergeant Major. “You ain’t.”

And indeed he isn’t. Not only is he a model of what a battlefield commander should be, he is also a pious, believing Roman Catholic and, for all his warlike spirit, a genuinely humble man. On the battlefield he recites from memory the De profundis — Psalm 129 in the Catholic numbering — which is one of the seven penitential psalms and traditionally associated with the dead and the souls in Purgatory. When Lt. Jack Geoghagen (Chris Klein) a new father and the one among his young officers to whom he feels closest (no prizes for guessing what happens to him) confides in him that he knows God has a plan for his life and hopes that it is to protect orphans and not to make them, Colonel Moore replies, “Let’s ask Him,” and the two of them sink to their knees side by side. But at the end of their prayer, the colonel adds: “One more thing, dear Lord. About our enemies. Ignore their heathen prayers and help us to send the little bastards straight to hell.” Golly! Can they say that in the movies?

The bad news, if you don’t count the position of honor given the North Vietnamese view of the action, is that the movie is way overproduced, as you might expect of the Randall Wallace/Mel Gibson (Braveheart) axis of eye-full. Make that way, way overproduced. Here it is not just the soldiers who go over the top. You know you are in Hollywood, and in particular Mel Gibson’s Hollywood, when even the scene of the men at Ft. Benning, Georgia, getting on the buses that will take them to their troop transports that will take them to Vietnam is accompanied by the sort of swelling music and lump-in-the-throat visuals usually reserved for inspirational endings. Messrs Gibson and Wallace seem to know no speed but full, no volume but full blast. Over two hours and twenty minutes this becomes emotionally fatiguing, so that we haven’t got so much to give as we ought to give to the inspirational ending when, inevitably, it comes.

Thus it is rather a good moment when the colonel addresses his troops before battle by saying, “I can’t promise you that I will bring you all back alive, but I can promise you that I will be the first one on the field and I will be the last one to step off the field and that I will leave no one behind. Dead or alive, we will all come home together. So help me God.” But is it really necessary to drive home the point with close-ups of the colonel’s boot both stepping off the helicopter’s skid at the beginning and stepping back on it at the end of the battle? And the full cast of army wives led by Mrs Moore (Madeleine Stowe), many of whose bereavements are intercut with the action on the field, could just about come under the heading of milking it. Likewise, a little bit less in the way of special effects might have produced a little bit more in the way of emotional oomph. I know this is heresy in Hollywood, but it has to be said and said again every time the tech guys — or the scenarists — go over the top.

But basically, though not so good a movie qua movie as Black Hawk Down, We Were Soldiers also has it right. Like Ridley Scott’s film, this one makes us believe in the peculiar magic, the miracles of courage and heroism wrought among ordinary men by training and discipline and esprit de corps. And in spite of a much more explicit and insistent patriotism (one dying soldier actually says “I’m glad I could die for my country”) it also understands the essence of military honor when it tells us, in the colonel’s voice, that his men “went to war because their country ordered them to, but in the end they fought not for their country or their flag. They fought for each other.” What’s the betting, though, that the New York Times and other snooty critics will find that those words are “jingoistic” too?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.