What Was the Founders’ “Sacred Honor”?

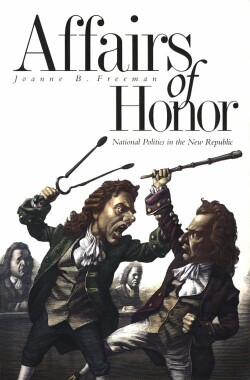

AFFAIRS OF HONOUR:

NATIONAL POLITICS IN THE

NEW

REPUBLIC

by Joanne B. Freeman

Yale University Press, 376 pp, $29.95

0 300 08877 9

Joanne B. Freeman, a young lecturer at Yale, has done some valuable and

pioneering work into the investigation of honour’s importance to the

founding of the American Republic. For an age in which the very word has an

alien, faintly repellent sound (we associate “honour” killings with

countries where women are bought and sold like cattle), she has done much to

explain its meaning and importance to those who were in the vanguard of

modernity for their time. Among the Founding Fathers, she tells us,

“Honour” was used interchangeably with “reputation” but

it meant “reputation with a moral dimension and an élite

cast”. It was, moreover, “the core of a man’s identity, his

sense of self, his manhood”, which is why even in those relatively

enlightened times it not infrequently involved men in single, and lethal, combat

over real or imagined slights.

To Americans, by far the most famous of all duels is that which was fought in

July, 1804, at Weehauken, New Jersey between two heroes of the War of

Independence: Colonel Aaron Burr, who was then vice president, and General

Alexander Hamilton, who had been the closest aide-de-camp of General Washington

and Secretary of the Treasury during Washington’s presidency. Burr killed

Hamilton, who had proclaimed his intention of firing above his opponent’s

head, destroying his own political career in the process. Miss Freeman devotes a

substantial portion of her book to this duel (recycling much of the material she

had earlier published in a seminal article in the William and Mary

Quarterly), showing how familiar all its elements were in the political and

social context of the early Republic — all, that is, save in its having

resulted in the death of one of the principals, which was a comparatively rare

occurrence.

The problem with the book is that, although the author several times shows

that she knows better, she persistently treats the 18th century

honour culture as if it were an indigenous product that grew up among the

American Founders as a result of their political situation and that presented

them with unique problems of reconciling the new democratic and republican

spirit with the demands of a traditional aristocratic code. Thus she writes that

“the code of honour did more than channel and monitor political conflict;

it formed the very infrastructure of national politics, providing a governing

logic and weapons of war”.

There were no

organized parties in this unstructured new arena, no set teams of combat or

institutionalized rules for battle. Political combat in the new national

government was like a war without uniforms; it was almost impossible to

distinguish friends from foes. National politics was personal, alliances were

unpredictable, and victory went to those who trusted the right people at the

right time in the right way.

The implication throughout her book is that the honour culture evolved in

order to give public men a way to cope with partisan confusion and fluidity. But

the honour culture long antedated the foundation of the Republic, and what looks

to the historian like a confusion of parties and factions was more likely the

consequence than the cause of honour’s influence.

More seriously, just as honour is seen as the result of the inchoate

political system, so Miss Freeman suggests that it disappeared with the

emergence of reasonably stable party structures — “a ritualized,

honour-bound, personal level of political interaction” having allegedly

“persisted until the anonymity of formal national political parties

altered the tone of politics forever”. Except that it didn’t. She

devotes no attention at all to it in the colonial period when it was already, or

the antebellum era in the South where it was still, an important feature of

daily life. Nor does she look beyond the American context, an excessive

concentration on which makes her paradoxically unable to give due emphasis to

what was genuinely new and original about the honour culture in the United

States.

This was the early association of the old aristocratic standard with a new

and democratic concern for public opinion.

When a duel was

particularly controversial (she writes) — when a duelist died or a chief

was involved — politicians capitalized on widespread public interest with

contending newspaper accounts, both sides attempting to win public approval

while dishonouring their foes. Regardless of his behavior on the field, a

duelist’s reputation depended on the success or failure of these publicity

campaigns. Political duels were won by the faction that best controlled public

opinion.

It is true that she quotes one contemporary who deplores this practice,

noting that “there is not another country in christendom — probably

not in the world — where the seconds in a duel. . . have the

presumption, immediately after the contest, to publish with the signature of

their names, a detailed relation of its commencement, progress and catastrophe,

together with encomiums on the gallant behavior of their respective

principals.” But how one wishes that she had pursued even one of

the several lines of inquiry suggested here instead of persisting in her

enthusiasm for making honour into nothing but a precursor of modern American

political parties.

For if, “under the two umbrellas of principle known as Federalism and

Republicanism lay a mass of shifting loyalties”, and “at various

points in their political careers, even men of seemingly ironclad principles

like Jefferson and Hamilton were rumored to have abandoned their supporters to

join with former foes”, couldn’t the same be said of politics in any

age? Though honour may have resulted in “blurred bounds between

socializing and politicking”, if you ask any congressman today where the

one begins and the other leaves off and he will be as vague as any Founder. And

if “honour was the ultimate bond of party”, or “the ultimate

bond of political trust”, was this not true at least up until quite recent

times? It might be stretching things to say that it is equally true today, but

the reaction to the party-switch of James Jeffords last year shows that there is

still a powerful residual sense of honour at work even in today’s party

politics, allegedly so remote (“most foreign to modern

sensibilities”) from the “link between personal honour and political

loyalty”.

In thus overstating the political role of honour, Miss Freeman understates

the extent to which it was present in all phases of life for those who were not

politically active but who could claim gentlemanly rank. In retrospect, it seems

to us that the “honour culture was an aristocratic holdover. . .[and]

hardly fit comfortably with an egalitarian regime”, but honour’s

interference with egalitarian principles would have been of much less concern to

those accustomed to speaking of their “sacred honour” than

egalitarianism’s interference with it. The real doubts about the honour

culture came in the United States as they did elsewhere from its conflict not

with egalitarianism but with religion, though about its moral dimension Miss

Freeman has little to say. The divided sensibility of those who submitted

themselves to what Hamilton called “public prejudice” while

suppressing their moral and religious scruples therefore also remains largely

unexplored. For all the marvellous contemporary information unearthed in this

book, its view of honour is limited by the narrow focus of the academic

historian.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.