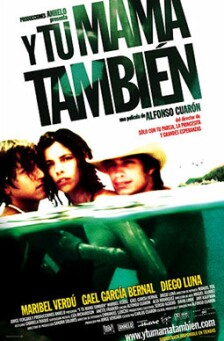

Y Tu Mama Tambien

Y Tu Mama Tambien (And Your Mother Too. . .) may be one of the best pornographic movies ever made, though Alfonso Cuarón (The Little Princess, Great Expectations) did not quite have the cheek to show us as much of his stars’ cheek, or other private parts, as a porn movie usually does. It is not the skin that makes this a porn film, though there is quite a lot of that. It is, rather, the ethos of the porn film which Cuarón has absorbed and presented to us with more than usual intelligence and savoir faire. This ethos — the very essence, as I take it, of pornography — is wish-fulfilment, and in particular the fantasy wish-fulfilment of sexually esurient teenage boys. Sr Cuarón knows that he is dealing in such debased artistic currency, however, and he wants to play with the expectations it naturally creates in us.

The boys in question are two Mexican friends about to go off to college, Tenoch (Diego Luna), the son of a prominent politician who wants him to study economics, and Julio (Gael Garcia Bernal), who comes from a much humbler background. As the film begins, both are saying good-bye to their girlfriends in exuberantly sexual fashion as they, the girlfriends, are about to leave on a European tour. Much of the first part of the film is taken up with their mutual assurances of their girlfriends’ likely fidelity, even among the fleshpots of Europe, and young-male bravado about their own potential exploits in their absence. Into their lives comes the wife of Tenoch’s cousin, the beautiful Luisa (Maribel Verdu), about whom both boys immediately start entertaining fantasies.

In order to impress her, the boys make up on the spur of the moment a beach trip to some place called Boca del Cielo, that perhaps they have heard of somewhere or perhaps just made up — a trip on which, with renewed bravado, they invite her to come. The weakest part of the film is the sequence of events by which the absurdity of Luisa’s acceptance of this invitation is meant to seem plausible. Her husband, who is on an out-of-town business trip, calls her late one night and drunkenly confesses to having an affair. Meanwhile, we have just seen her in her doctor’s office waiting room taking one of those women’s magazine quizzes designed to test how romantic you are. The way in which the doctor closes the door of his consulting room when he is about to give her the results of certain other tests tells us — well, see if you can guess what it tells us.

The silly magazine test is a nice, stylish touch, and not an untypical one. Cuarón is constantly looking to one side of his story: to the death of a peasant bricklayer in Mexico City that delays traffic as the boys are returning from taking their girlfriends to the airport, to an accident on the same road but several years before as the threesome drive to the mythical Boca del Cielo. In one memorable scene at a wedding attended by the president of the republic and other government bigwigs and industrialists, mention of the many bodyguards is illustrated as we see a waitress bringing out food to a veritable crowd of them, with drivers, standing among the Jaguars and Mercedes in the parking lot.

It is a good technique for a road movie. The passing parade makes itself known more than usual as the focus shifts briefly to a beggar in the restaurant where they stop on the first night, or an old woman dancing. But the sideways glance technique is also carried out here when the soundtrack goes dead for a moment before the voiceover comes on to explain or give a bit of background. Most notably there are predictions given in voiceover that are reminiscent of French new wave technique — and not the only similarity with Truffaut’s Jules et Jim. This stopping of the sound while conversations apparently continue on screen gives the sense of a lecturer or critic pointing to illustrations as he pauses the film. The didactic effect is unfortunate.

For it is the pornographic purpose which remains foremost. There are a number of teases that seem to go right up to the edge of what in the popular culture is generally taken to define porn — namely graphic images of the erect penis and/or penetration — and then draw back. But we don’t ever quite get there. Nor do we get the “money shot” associated with porn — nor the cheesiness nor (apart from Luisa’s agreement to come with them, which is the donné of the film) the risible contrivances of plot and characterization by which improbable sexual couplings are meant to seem real. What we do get, is the teenage boy’s view of sex as the sole and sufficient end of life — though along with this, I think, the suggestion that maybe the studied pretense of almost all pornography, namely that casual and promiscuous sex is indulged without cost or consequence, cannot be sustained.

Even so much skepticism as that about the pornographer’s fantasy might have been enough to redeem the film, but somewhere behind its momentary doubt there still lurks the hippie dream, the belief that sexual freedom equals happiness, which was one of the two great delusions of the 20th century. Cuarón would have done better to stick more closely to his model, the great Jules et Jim, whose final note of doubt is definitive. Instead, he has said that “this film is about two teenage boys finding their identity as adults and a woman trying to find her identity as a liberated woman. . .It’s also about the search for identity of a country going through its teenage years and trying to find itself as an adult nation.” It’s true that there is some mildly interesting sociological commentary implied in the tension the “peasant” Julio and his friend, with his father in the government and his fashionable Aztec name, who is said to be a “yuppie” or “preppie.” But anyone who sees any “liberation” in any of this will, I fear, never have much of interest to say.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.