The Paranoid Style in American Journalism

From The New CriterionFive months — almost to the day — after September 11, the consensus on the terror attacks and their aftermath, The Story according to the media, suddenly changed. Of course, it was never on the cards that the original Story, of American heroes chasing down and eliminating fanatical foreign evil-doers, was going to last. President Bush may himself have hastened its demise with the phrase in his State of the Union address about the “axis of evil.” However popular that description of some of the prime sponsors of terrorism or developers of terror- weapons may have been with the majority of Americans, it was decidedly not a hit with journalists — any more than it was with foreigners, to whose opinions journalists tend to be more sensitive than the rest of us. Neither journalists nor foreigners much liked Bush’s foray into what the European Community’s commissioner for foreign policy, Christopher Patten, described as “absolutism.”

Then, too, there was at the time no major military campaign to occupy the attention of the army of journalists in Afghanistan and some dissatisfaction over the unfortunate fact that the most prominent of the fanatical foreign evil-doers, Osama bin Laden, had not yet been caught in spite of all the other successes against the al-Qa’eda terror-network and their Taliban sponsors. But, for whatever reason, from the 10th of February at least until the fighting flared up again — and there were more American casualties — in early March, the media, led by those bellwethers of the journalistic flock, the New York Times and the Washington Post, began to give a new emphasis to what they saw as the failings and shortcomings of the American military and diplomatic effort against terrorism.

“Uncertain Toll in the Fog of War: Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan,” the Times that day headlined a story by Barry Bearak and others which told of a raid by American special forces on January 24 in which some innocent villagers in the Oruzgan province had been killed or arrested in the (apparently) mistaken belief that they were al-Qa’eda members. Between 15 and 21 had been killed and 27 had been imprisoned for 16 days. The next day, under the Post’s headline “Casualties of U.S. Miscalculations,” an article by Doug Struck described how, on February 4th, a remote-controlled, “Hellfire” missile had blown up three Afghan scrap collectors in the equally mistaken belief that one of them — taller than the others and the object of some deference on their part — had been Osama bin Laden.

Struck even included with his report the thrilling detail that he himself had been stopped at gunpoint by American soldiers from getting close to the scene where the supposed scrap-collecting peasants had been blown to bits. “This is an ongoing military operation,” he claimed the soldiers’ commander had told him. “If you go further, you would be shot.” Later, a Pentagon spokesman said that what the commander had actually said was it was dangerous up ahead and that, if Struck went on, he might be in danger of being shot — presumably by the enemy and not by his fellow countrymen — which Struck said was “an amazing lie.” The following day, he reported it as a matter of fact, on the strength of an interview with a man claiming to be the uncle one of the three victims, that they had indeed been innocent peasants in search of scrap.

In this desperate land long raked by combat, the debris of battle quickly becomes a prize for the scavengers of war. That was why Jahan Gir and his two friends were at a bombed al Qaeda camp when they were hit last week by a U.S. missile, their relatives say.

“They knew there were airstrikes there a few days before, so they knew they could find scrap metal,” said Janat Khan, Gir’s uncle. “They knew there was a risk, but they had to feed their families.”

Struck attempted to give an enhanced importance to his claim by writing that

The deaths of the three men [on] Feb. 4 in Zhawar. . . might have passed as the unfortunate consequence of war had the Pentagon not claimed that the victims of the rocket attack were senior members of al Qaeda, and that one of them might have been the group’s founder, Osama bin Laden.

When the Pentagon denied that the men were “scrap collectors” and insisted that they were up to no good, Howard Kurtz’s media column ran with the witty headline: “Pentagon Gets Defensive.” Could there be a scandal a-brewing? Please? Please?

Or, if not there perhaps, what about the allegations by some of the 27 innocents imprisoned in Oruzgan that they had been beaten in captivity? A few reports noted that al-Qa’eda had instructed its fighters to make, if captured, precisely such allegations as this, though for most the burden of proof that they had not been beaten rested with the U.S. government. The supposed beatings could thus be linked with the deaths of the supposed scrap collectors as a kind of corroboration of the new Story’s doubtfulness about American tactics — this even though the Pentagon had acknowledged error in the one case but not in the other. Thus James Dao in the New York Times: “Questions about the attack [on the scrap collectors] come on the heels of assertions by officials in Oruzgan Province in central Afghanistan that American troops mistakenly attacked a group of anti-Taliban forces last month, killing at least 15 people and capturing 27.” Ah, yes. Questions.

The underlying assumptions of the new Story were more congenial to the journalistic mentality than those of the old, according to which they were meant to be the cheerleaders to the American and allied military effort rather than the referees. Now they were again enabled to step off the field and adopt their favorite posture of “objectivity,” studiously avoiding any questions which might have entailed commitment to winners or losers and concerning themselves only with those of how, so far as they could see it, the game was being played. But although the focus on civilian casualties was natural from an Afghan standpoint, it was unnatural from an American one. It got the proportions wrong, losing sight of the reasons why the war was being fought in the first place and the inevitability of hardship and danger for those among whose daily lives it was being fought.

Of course it is quite understandable that the reporters should get tired of the five months’ focus on President Bush’s “war against terrorism.” The attention of their readers, too, must have wandered in the absence of any dramatic battles or troop movements, or the killing or capture of Osama bin Laden. But the journalist’s first responsibility is not to the market, or the attention span of his audience, but to the truth, and the truth here must be supposed to include that sense of proportionality that is sacrificed when the point of view shifts from American to Afghani for the sake of freshness and interest.

More important, perhaps, than the need for freshness was the need for a larger familiarity, for a context to contain The Story more familiar than that of Islamic fundamentalism and religious and national tensions in Central Asia. For the Post’s columnist, Richard Cohen, the scandal was not the deaths of the Afghan peasants — mistakes do happen — but the claims of beatings by American soldiers and the fact that they had interfered with a journalist, Mr. Struck, in the lawful performance of his sacred duty to try to find out — well, anything that authority did not want him to find out. “It is one thing to bomb or attack on the basis of misinformation,” wrote Cohen. “It is quite another thing to abuse prisoners captured as a result. It is also quite another thing to threaten the life of an American journalist.” Determined to get all that he could out of his little quite-anothering antithesis, he went on to raise the “specter” of My Lai and crushingly added that “it is one thing to fight the enemy. It is quite another to fight like him.”

Let’s see: My Lai is like al-Qa’eda is like U.S. soldiers running riot — or at least giving signs that they might, once again, run riot by threatening a journalist, who is therefore like a helpless Vietnamese peasant. Somewhere in that thicket of analogy, the reader is likely to lose the thread. But the old reliable, Frank Rich of the New York Times was in some ways even more hysterical than Cohen when he attempted to link the murder of Daniel Pearl, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, by Muslim fanatics in Pakistan with the government’s attempt to manage the news. “Not since the Nixon years,” he wrote, “has an administration done as much to stymie reporters who specialize in the genre of investigative inquiry Mr. Pearl was pursuing when he was ambushed” — and he went on to mention the detention of poor Mr Struck as “the most chilling example.” Such examples are always chilling.

Cohen had already mentioned Vietnam and My Lai, now Rich was adding Nixon and Watergate. Together the two served as a reminder that, for those who came of age in the 1960s and who now dominate the journalistic culture, all foreign and defense stories tend to degrade to echoes of Vietnam — just as all political stories tend to degrade to echoes of Watergate and all social stories to echoes of the civil rights movement. Any history prior to McCarthyism (proto-Vietnam/Watergate) or the Holocaust (proto-civil rights) is irrelevant. Naturally, as journalism played a central role in all three of these nodal, transformative historical dramas, the heirs of the media heroes of yesteryear look for new opportunities of the same kind to become heroes themselves — like generals fighting (as generals are always said by the media to do) the last war.

Why shouldn’t the mistaken deaths of Afghan peasants recall My Lai? Why shouldn’t U.S. military policing of free-ranging war correspondents — whose purposes are proudly announced to be at variance with those of the American government and armed forces — suggest semi-official “enemies” lists of journalists? And if there were lots of reasons why they should not, what were these to the one big reason why they should, namely the justification of journalism’s exalted ideas of its own importance? If you begin with the assumption that the truth is hidden and that it is the job of self-styled independent-minded journalists to dig it out, then any truths so hidden and so dug will naturally be privileged over the truths that are just lying around, waiting to be picked up. This is also why those who have learned how to use the art of leaking will always have the press as their instrument.

The other, equally important, way in which journalists see their services as being indispensable to us is in teasing out the nuance — the “shades of gray” to use the well-worn metaphor invariably employed on these occasions — between the absolute oppositions or “black-and-white” in terms of which politicians, generals and all those thought to be less clever than journalists are said to think. Thus Karen DeYoung lost no time in announcing on the front page of the Post on February 12th that

The Afghan war, so easy to understand in its early, black and white days, when President Bush proclaimed that the world could be neatly divided into us and them, has lately taken on shades of gray.

“To say the conditions in Afghanistan are confusing is an understatement,” Pentagon spokeswoman Victoria Clarke said yesterday in a rare public display of frustration. “And it’s impossible to say these people are on this side and these people are on the other side. People are on multiple sides, and they switch sides.”

The U.S. military, accustomed to being the undisputed good guys in this conflict, has grown defensive over reports of possible errors. . . It is almost as if the administration fears that any admission of fallibility will cause overwhelming public support for the war at home to collapse — and for key partners abroad to withdraw their backing. . .

The “multiple sides,” like civilian deaths and injuries, suggested to many the infamous “quagmire” of Vietnam. More signs of just how “murky” war was said to be came with U.S. air action against one Afghan war-lord on behalf of — or so it was suspected by Michael Gordon of the New York Times — another. Though official spokesmen said that the bad war-lord was a former Taliban man who was smuggling al-Qa’eda fighters out of Afghanistan while the good war-lord was working for the new Afghan government, “officials also acknowledge that the intelligence is unconfirmed and the exact composition of the enemy force still unclear.”

The Times’s reporter seemed to think it would have been a considerable embarrassment to the U.S. if it were shown “that the Americans were intervening on the Afghan government’s side in internal fighting in Afghanistan” since American government “officials” had made “an effort to rebut” any such allegations. Since the officials did not know whom they had bombed and shot at but only that whoever it was had shot at the leader appointed by the Kabul government and his men and, later by a force in which American special forces soldiers were also included, such “assertions by Afghan commanders” of American interference with the rights of Afghan warlords to shoot at each other could not be dismissed.

This story was linked to the mistaken attack story by Alan Sipress and Walter Pincus in the Washington Post, since

The costly raid on pro-American villagers in Hazar Qadam highlights the mounting danger that U.S. forces will be sucked into the simmering chaos of Afghanistan, with consequences not only for the local population. The daunting security situation cited by Rumsfeld in his defense of U.S. conduct raises questions about the U.S. military’s ability ultimately to extract itself as the campaign against al Qaeda and Taliban fighters winds down.

Hence hints of the “quagmire” and “escalation” paradigms associated with Vietnam — if, that is, there was “a more extensive role for the U.S. military than first envisioned when American troops launched their hunt for Osama bin Laden and his followers.” Sipress and Pincus go on to suggest that as many as 25,000 peacekeeping forces (there are now only 4000 projected to be needed) might be required to keep order and suppress the warlords. “Escalation,” anyone?

But the outcry for “shades of gray” was never louder than in response to President Bush’s remarks about the “axis of evil.” Such language recalled the Cold War for Mark Lilla and Robert F. Worth both of whom wrote in the New York Times. Worth was particularly concerned:

As President Bush toured Asia last week, some world leaders worried publicly that the war on terrorism was starting to look suspiciously like the last great American campaign — against Communism.

It is hard to miss the cold war echoes. Once again America’s allies are being told that the world is divided starkly into zones of good and evil, darkness and light, and that “the United States and only the United States can see this effort through to victory,” as Vice President Dick Cheney told a gathering at the Council on Foreign Relations two weeks ago.

Worth was given considerable space to retrace the history of America’s regrettable tendency to believe in evil in order to lay out, with an analogical abandon worthy of Richard Cohen, the precedents for this latest exercise in black-and-white thinking:

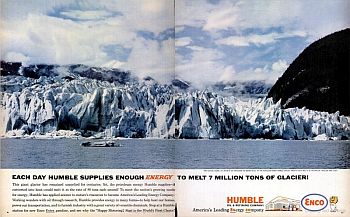

The language Mr. Bush and others have used to describe Al Qaeda terrorists sometimes sounds as though it could have been written by Cotton Mather. Ever since the Puritans arrived in New England, civic and political leaders have often issued the same warning: sinister conspirators are spreading invisibly through the land, a cabal of evil and dangerous men who are bent on subverting this shining city on a hill. As Attorney General John Ashcroft put it recently: “A calculated, malignant, devastating evil has arisen in our world. Civilization cannot afford to ignore the wrongs that have been done.”

The words are meant to be discredited by association with Cotton Mather and others — most notably and inevitably Joseph McCarthy — without their actual import ever being examined at all. True, Mr Worth says that

This is by no means to suggest that the terrorists who struck on Sept. 11, or who kidnapped and murdered the Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, aren’t evil, or that it is not necessary to say so. But when the nation’s enemies are used as highly emotional political symbols, it becomes easy to lose touch with the reality of their acts and motives — and thus fail to better understand how to defeat or influence them. It is not hard to see in Mr. Ashcroft’s language traces of what the historian Richard Hofstadter famously described as “the paranoid style in American politics.”

Enough said! The important consideration about such language is not its truth or falsity but whether or not sophisticates like himself, or Richard Hofstadter, or others of his academic experts, look upon it with disdain. What else should matter to readers of the New York Times? It is the same approach they were encouraged to take to Communism. Yes, perhaps the Communists had done some very bad things, but it was a sign of national pathology — “the paranoid style” — to call attention to the fact, or to act forcefully upon it. Thus, inevitably,

The McCarthy years in some ways were eerily similar to the present moment. For example, Samuel Stouffer, a Harvard sociologist doing research on attitudes toward Communism in the early 1950’s, found a generalized anxiety that the country was under attack by unseen enemies bent on global domination.

Worth notes that “While all nations regard their causes as just, and all demonize their enemies, the combination of American might and its longstanding self- image as uniquely virtuous irritates even its allies” — as if “all nations” did not also, besides regarding their causes as just and their enemies as evil, irritate their allies, especially where the allies are much less powerful! “Why has that phrase, ‘axis of evil,’ crystallized so much anti-American sentiment around the world?” one of Worth’s historical — and near-hysterical — experts, Professor John Dower of M.I.T. is quoted as saying: “Because the country sees itself as nothing but good and innocent, and that infuriates people.” Yes, and he might have added that when countries really are good and innocent it infuriates them even more.

With wonderful irony, Worth concludes that although “terrorism does present a real threat” and “cold-blooded killing presents a moral outrage” (handsome concessions!) “the history of American crusading, even against unmistakable evil, suggests that it can be more effective to start from a position of humility. Righteousness easily becomes self-righteousness, and it can be hard for crusaders to distinguish between the two.” And there you have it: a lesson in humility from The New York Times. You won’t find anyone “uniquely virtuous” or “good and innocent” in these pages, will you? Thank God for such a bulwark against the self-righteousness of George Bush!

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.