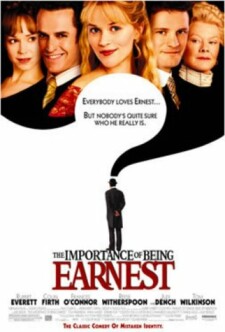

Importance of Being Earnest, The

Every age suffers from the vices appropriate to its virtues. The Victorians — earnest, idealistic, pious, prudish about sex — were martyrs to hypocrisy, which a clever non- hypocrite with none of their virtues, like Oscar Wilde, could mercilessly ridicule. In this sense, Wilde was the first 20th century man, though he died before the century was actually underway. His own virtues — wit, brilliance, taste, frankness about sex — were also those of the century to come, and he shared to the full in the corresponding vice of self-indulgence. Yet, paradoxically, he is also now unimaginable outside of the Victorian context, to which he is pinned like an etherized butterfly on a piece of cardboard.

Unlike the protean Shakespeare whose plays are hardly ever presented anymore without being made to shed some light on a period not their own, Wilde entirely belongs to the Victorian twilight of the 1890s and his plays are completely unimaginable anywhere else. Oliver Parker’s movie version of The Importance of Being Earnest, following on from another of An Ideal Husband three years ago, is further proof of how our contemporaries never tire of laughing at the absurdities of Victorian hypocrisy, as if such hypocrisy still existed, as if it were still a live thing, as if the vices and absurdities of our own time were not also worth laughing at, had we the Victorian capacity for self-criticism and could laugh at them.

But, like so much of 19th century art, Wilde’s plays have become their own museum, a place where passion and danger are made safe and tasteful and the occasion for much self-congratulation on the part of those who patronize them. Wilde is like the priest in Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn” — frozen in time as he leads the heifer to the altar for sacrifice. Forever wilt thou strike at Victorian hypocrisy, O Oscar, and forever shall Victorian hypocrisy look up with its big, brown, bovine eyes at thy knife descending — and remain unslaughtered.

Parker, divining something of this static, inert quality in the play, makes several ill-advised attempts to break out of its time-shackles by, for instance, including an easy transition on the soundtrack from a vaguely period-consistent but still too early ragtime melody picked out by Algy (Rupert Everett) on the piano to a much more swinging number called “Lady Come Down” that could not possibly have been heard by human ears until thirty or forty years later.

Other examples of a whimsy that is not quite Victorian whimsy include Algy’s arrival at the country seat of Jack/Ernest (Colin Firth) in a balloon and Algy’s servants hall mounting a little jug band, with Lane (Edward Fox) on the tuba. But the worst thing Parker does is to make the alliance of Cecily (Reese Witherspoon) and Gwendolyn (Frances O’Connor) into a proto-feminist cell, as the two smoke cigarettes together and listen to rag-time. Gwendolyn also asserts herself by leaving home behind the wheel of an early motor-car and even getting a tattoo (of the name “Ernest” of course) on her bottom.

Such hints of the coming of a raised feminist consciousness and even of sexual license have the curious effect of making the play seem even more dated than it would in any case seem, since the Wildean world was brought to an end forever precisely by such unwillingness of feminists to stand for the old hypocrisies of which he makes so much. It is quite enough that, in the original play, Gwendolyn and Cecily and, indeed, Lady Bracknell, must demand an end to Bunburying when it is forced upon their attention. The whole point of the secrecy and the hypocrisy was that they should not know what men got up to when they were away from them.

For the great revelation of Wildean humor lay in its treatment of the officially sanctioned decencies, designed to protect such feminine innocence, as being as much of an amusing charade to the women as to the men. Wilde’s heroines positively delighted in the discovery of their men’s “Bunburying,” or inventing friends and relatives as a cover for sexual adventures — as how else should they have had the chance to exercise their feminine power of being shocked? Of course, the decencies could not long survive such treatment, and did not. But to depict the play’s heroines as premature feminists, who sought quite different feminine powers by pulling down the whole Victorian façade of pretense and hypocrisy is not only untrue to Wilde, it is not to understand what the play is about.

Another device that I don’t think works at all is the introduction of fantasy sequences. The film opens with Algy’s pursuit through a foggy London streetscape by his creditors. Other useless passages show the depositing of the handbag containing the infant Jack Worthing in the cloakroom at Victoria Station and a preposterous sequence in which a youthful Lady Bracknell steps out of the chorus line to force the late Lord Bracknell to marry her by revealing her pregnancy, as if they were a couple of middle-class high school kids of the 1950s. Almost equally preposterously, when the romantic Cecily imagines her knight in shining armor, poor Rupert Everett has to don the armor in a pre-Raphaelite tableau.

Not only does he look ridiculous, but so does Reese Witherspoon got up to look like a pre-Raphaelite beauty. She has too much of that brittle, sophisticated look of young beauties today to be quite persuasive in the role of the innocent Cecily. She does not surprise us enough when she shows us what she really understands. Another pre-Raphaelite tableau comprises even the Rev. Mr. Chasuble (Tom Wilkinson) and Miss Prism (Anna Massey), perhaps to ridicule that idealization of chivalry as an adjunct to and corollary of — which it was — the sexual prudery of the period. But it only emphasizes the extent to which the play’s own satirical quarry is long dead and buried and that it seems positively ghoulish to continue feasting on it. Pre-Raphaelitism forsooth! It’s like ridiculing belief in the Ptolemaic universe.

Fortunately, another corollary of the play’s unremovability from its social context is that the steady flow of witticisms and comical situations thrown up by the manners of the period is hardly affected by any of this conceptual confusion, and fine performances by Messrs. Everett, Firth and Wilkinson, Miss Massey and Dame Judi Dench as Lady Bracknell mean that one’s time can hardly be wasted.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.