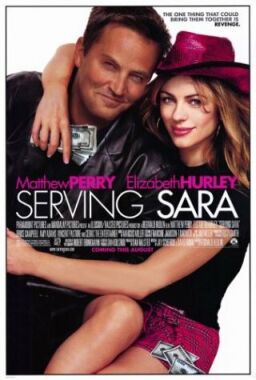

Serving Sara

Here is the story we are asked to accept as the basis for the plot of Serving Sara, directed by Reginald Hudlin and written by Jay Scherick and David Ronn. Joe (Matthew Perry) is a successful lawyer who one day, in the course of defending a mafia client, decides that he has become a “cliché” and quits the legal profession in order to become a process server. The life, as you might imagine, has its ups and downs — the latter including getting beaten up by mafia thugs and insulted and betrayed by his half-witted colleague, Tony (Vincent Pastore) — but it is doubtless his sense of the social importance of the job he does which sustains him. Or at least it does until one day when he accepts a large bribe and disappears.

Now you have to ask yourself, why would someone so principled that he declined to get rich doing legal (if unsavory) work then go on to enrich himself by doing something both dishonorable and illegal? Could it be for love? At first it seems an attractive theory. The bribe is offered by a beautiful Anglo-Texan trophy wife, Sara Moore (Elizabeth Hurley), whom Joe serves with divorce papers. Sara, if served with Texas papers, stands to get much less in the divorce settlement than she would if the case were heard in New York, and she offers Joe ten per cent of her estimated winnings of $10 million for pretending he hasn’t served her — and serving her rat of a husband with New York papers before anyone else can find her on his behalf.

Yet the film refuses to take this easy way out. From the start it is clear that Joe “flips his mark” — or, in less arcane language, commits perjury and abuses his trust as an officer of the court — for the money. The subsequent romance that develops (inevitably) between himself and Sara seems tacked on as an afterthought, as much to the two lovers as to the audience. And when it seems for a time that Joe has failed and Sara has been served first after all, Joe accepts his instant dismissal from the alleged object of his affections with as much equanimity as he does his re-admission to her good graces when hope is renewed.

The only moment when the film troubles itself to suggest any foundation to their relationship other than sex comes when Joe confides in Sara that it has been his lifelong dream to own his own vineyard, and she appears to think it a cool ambition. Motivation at last! In the old days, before the scrapping of the Hays Code — which decreed that movies couldn’t show criminals prospering from their crime — we used to love the hero in a romantic comedy because he was poor but honest. The good guy was genuinely good. When he outwitted the crooked rich guy to win the girl and the money, we cheered because virtue had been rewarded — and we cheered the more because we knew that virtue was too often not rewarded in real life.

Lately, however, the trend in the movies, and perhaps in real life too, has been to substitute a kind of charming roguishness and skill in witty repartee for virtue. Instead of the good guy’s winning, the cool guy does, and hardly anyone seems to notice the difference. It’s like the dumbing down of educational standards. After all, it’s easier to be cool than it is to be good. And in the land of the fabled “American dream,” the dream factory of Hollywood has decided that the guy who dreams of a vineyard must have his vineyard without having to bother about every picky ethical detail.

Not that there are not some funny moments along the way. Mr Perry’s talent for looking lovable when getting into humiliating scrapes and Miss Hurley’s talent for looking beautiful while getting him into them carry us along more or less painlessly through a frantic chase across the state of Texas after the erring husband (Bruce Campbell) as they are themselves being pursued themselves by stupid Tony and their boss Ray (Cedric the Entertainer) who has mildly amusing manic fits while directing Tony’s movements by phone from New York.

Tony is another example of the trend by which the only human infirmity which it is still permissible to mock and ridicule is stupidity, which is what you’d expect from a culture in the hands of what Charles Murray calls a “cognitive élite.” It also suggests from whence comes the assumption that it is better to be smart and rich than good and poor. Unfortunately, the movie’s best evidence for Joe’s being smart is its attempt to make him a master of witty repartee. So when Tony says, “Eat me!” Joe ripostes, “I’ve never been that hungry.”

A little less than Wildean, I think you will agree. Another of the film’s jokes comes as Joe, during his first, chaste night in a hotel with the beauteous Sara, picks up and pretends to read a Gideon’s Bible as a means of mockingly signifying his unwilling celibacy. Sara turns off the lights immediately, and Joe snaps the Bible shut, ruefully saying, “I think I got the gist of it.”

Maybe he should have stuck with it for a few more minutes.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.