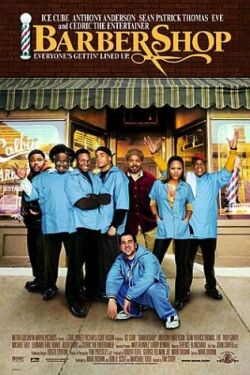

Barbershop

At one point in Barbershop, the old barber Eddie (Cedric the Entertainer) who never seems to cut any hair but who is always pontificating about something or other looks around to make sure that no white people are listening and then says what otherwise he wouldn’t dream of saying — that “Rosa Parks ain’t do nothin’ but sit her black ass down,” that “Rodney King should have got his ass beat” and that “O.J. did it.” And when one of those who have listened open-mouthed to such heresy says, “Don’t let Jesse Jackson hear you,” he replies “F*** Jesse Jackson.”

There is about the film as a whole something of this heretical quality. There are, understandably, things that black people can say among themselves (like the famous n-word) that they would never tolerate from anyone else. And so the film seems almost to have set out to resemble the old “Amos ‘n’ Andy Show” but made by black people — most notably director Tim Story — and for black people. This is both its strength and its weakness. On the plus side, we are invited into the circle of the initiate where the racial pieties of Jesse Jackson no longer need be taken seriously. On the minus side, our place there is bought at the cost of rather a lot of alternative moralizing.

One doesn’t wish to seem ungrateful. Not only are there genuine comic moments of charm and accomplishment — particularly in the continuing saga of the attempts by J.D. (Anthony Anderson) and his simple-minded accomplice, Billy (Lahmard Tate) to break open an ATM they have stolen — but the moralizing is (I believe) mostly of an entirely salutary kind. For example, when the taciturn ex-con, Ricky (Michael Ealy), suddenly bursts into a discussion of “reparations” for slavery by saying that “We don’t need reparations, we need restraint,” the shock is almost as great as it is on hearing Eddie say that O.J. did it.

We know, that is, that the association between black culture and black poverty is, officially, “blaming the victim.” But, once again, when the guard is down and Jesse Jackson isn’t around to hear, home truths may be spoken out loud in spite of such taboos. After all, asks Eddie — the man for whom the shop is “the cornerstone of the neighborhood”, “our own country club” and “a place where black man means something” — “if you can’t talk straight in a barbershop, where can you?”

The story that rather loosely ties together the miscellaneous conversations of the barbershop, and ultimately the antics of J.D. and Billy, is also admirably clear-sighted for the most part. Calvin Palmer (Ice Cube) has inherited the barbershop from his now-deceased father but dreams of selling up and getting into the recording business. Briefly he succumbs to the temptation of an offer from the local loan shark (Keith David), who wants to turn the place into a strip club but, persuaded with the help of his tough-minded wife (Jazsmin Lewis) of Eddie’s view of the importance of the barbershop as a center of the respectable community, he has to get his shop back even at the risk of his life.

For Calvin, the recording business is a pipe dream, just as reparations are the pipe dream of the larger community. And the barbershop is full of people who think they are too good for it. “Nobody in here want to be a barber for the rest of they life,” says one of them. But the one of them who already has been a barber for the whole of his working life, Eddie, again sets them straight: “In my day a barber was a counselor, a fashion expert, style coach, an all-round hustler… The problem today is that you got no skill, no sense of history. You got the nerve to want to be somebody. You want respect. But you got to show respect to get respect.”

I’m not quite sure how all this hangs together, but it is clear enough that Eddie stands for reality and against fantasy. I also don’t know to what extent the self-deceptions of nearly all the characters — mostly dreams of the glamorous lives of celebrities like Oprah Winfrey and Steadman Graham — are or can be shed, but the message that they should be shed is hammered home with such didactic insistence that we wish in the end for more of J.D. and Billy. They represent the Amos ‘n’ Andyish element that the over-earnest film-makers are elsewhere trying so hard to discredit, but that they seem secretly to love as much as we do.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.