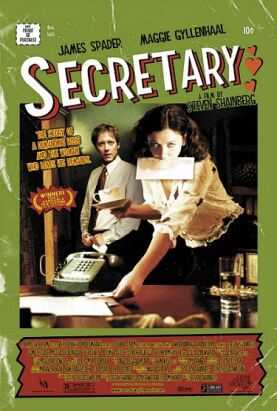

Secretary

Both “secret” and “sex” are suggested by the very name of “secretary” and the job description carries within it what to the male imagination anyway, and perhaps to some women, is the alluring suggestion of a dominant/submissive relationship — boss man and hired woman — that falls just this side of the pathological. There is something, too, to appeal to the sado-masochistic personality in the clatter of an old-fashioned typewriter, the striking of metal on paper to leave a lastingly legible impression. That is why, I take it, Secretary, Steven Shainberg’s film adaptation of a story by Mary Gaitskell, begins with the image of an IBM Selectric “golfball” typewriter, the latest in cutting edge office technology in the 1970s, which Mr Edward Grey Esq. (James Spader) insists on using instead of computers in his Florida law office.

When Lee (Maggie Gyllenhaal), who has just been released from a stay in a mental institution, takes a job as his new secretary, we have already been prepared for the development of some kind of weird sexual relationship. Lee, we know, lives in what we nowadays call a “dysfunctional household” with a drunken, abusive father and an over-protective mother. She has developed a habit of cutting herself which her institutionalization has not broken. After taking a secretarial course, she sees getting a job as a secretary as the land of heart’s desire, symbolizing her return to normality. This means that she is willing to do anything. When Mr Grey warns her that she is overqualified for such dull work, she insists: “I want to be bored. . .I like dull work.” See if you can guess what’s coming.

There must be something in Mr. Spader that draws him to movies about psycho-sexual dysfunction — sex, lies and videotape, Crash, and The Watcher, for example. Secretary, to its credit, tries to be a little less kinky. Or rather, to suggest that Mr Grey’s kinkiness and its willing indulgence by his pretty young secretary have something to tell us about “normal” life too. There is a little bit of probing around the edges of the legitimate boss’s right to dominate. “I think I accidentally threw out my notes on the Feldman case,” says Mr. Grey tentatively. ” I thought you could. . .”

“Go through the garbage?” asks Lee brightly.

“Yes, Lee. Thank you.”

From the dumpster, where he watches her wading with interest (“It’s OK,” he says as she returns from her fishing expedition in triumph, “I found another copy”), the relationship moves on to spanking (Mr. Grey really doesn’t like typos in his typewritten letters), and Lee gives up cutting herself when ordered to by the boss, one form of masochism presumably driving out another. There are some funny moments as when, for instance, we hear her on the telephone to the boss just as she is about to sit down to a family dinner. After telling him what they are having, she is told exactly what she can eat: “one scoop of creamed potatoes, one pat of butter, four peas, as much ice cream as you want.” She finds greater and greater intimacy, greater and greater fulfilment in submissiveness, with Mr. Grey — who himself, however, keeps his distance and eschews conventional sexual relations.

Jeremy Davies does a good job as Lee’s doting but oddly clueless boyfriend who can’t take a hint when she hopefully brings her masochism to bed with him, but even he, like mom and dad and doctor, fades out of the picture with its roseate view of symbiotic pain. The odd thing about it to me, however, is the happy ending, with its implication of a paradoxical pleasure and fulfilment, such as we associate with marriage, for people who like to suffer, or to cause suffering. In this it strikes one as being, to our times, like the ending of The Taming of the Shrew — slightly indecent. More so, at any rate, than any weird, sado-masochistic sex between boss and secretary could be. Here, the romance of the secret psyche and its hidden wounds becomes the source of intimacy and happiness, but I can’t see many people buying it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.