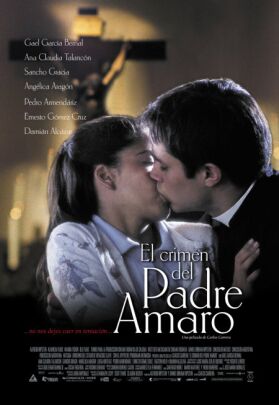

Crimen del Padre Amaro, El

Americans talk about a “culture war,” but in Mexico they are still fighting — and bitterly fighting too — a culture war that has been going on for over a century. For not only do they have Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, in Julie Taymor’s Frida, pushing the dear old Bolshevik revolution as if it were still the 1920s, now they also have Carlos Carrera’s vitriolic anti-clerical morality play, El Crimen del Padre Amaro, as if it were still the 1870s — which is when the Portuguese novel by Eça de Queirós on which it is based was written.

Carrera has updated the story to the present day and set it in rural Mexico. Padre Amaro (Gael García Bernal) comes to the little country town of Los Reyes to assist the local priest, Padre Benito (Sancho Gracia). The latter, it turns out, is not only sleeping with the proprietress of the village cantina, Sanjuanera (Angélica Aragón), he is also building a hospital by helping a nearby drug lord launder money. Padre Amaro seems a different sort of guy: genuinely pious and eager to serve. But he swiftly catches the eye of Sanjuanera’s beautiful daughter Amelia (Ana Claudia Talancón) who tempts him to break his vow of celibacy.

At the same time he is undergoing other sorts of temptation. Padre Natalio (Damián Alcázar), a political priest of the “liberation” tendency is in trouble with his bishop (Ernesto Gómez Cruz), and Amaro becomes the bishop’s messenger to tell him to shape up or ship out. As his ministry appears to consist of serving as chaplain to the local guerrillas, he ships out, and Amaro is obviously upset to see so good and holy a man leave the church. He knows Natalio’s ideals are the right ones, if you follow me, but he has no more ability to act in accordance with his conscience there than he does with Amelia.

Meanwhile, Amelia’s ex-boyfriend, Rubén (Andrés Montiel), the son of the village atheist, Paco (Lorenzo de Rodas), publishes an exposé of Father Benito’s connection to the drug traffickers and Amaro is given the task of threatening the editor of Rubén’s newspaper with the Bishop’s sanction on his advertisers unless he publishes a retraction. The editor gives in to the pressure, sacking Rubén who is forced to leave town to find work. Meanwhile, Amaro and Amelia are exploiting the latter’s supposedly humanitarian visits to Getsemaní (Blanca Loaria), the retarded daughter of the Sacristan, Martín (Gastón Melo), as a cover for their sordid assignations.

Martín, as is readily apparent, represents the wise and rueful eyes and ears of the eternal peasantry, oppressed for so long by the Catholic church, and the image of Getsemaní being force-fed the eucharist or clutching the crumpled image of God as torn from Amelia’s illustrated catechism makes the point with characteristic heavy-handedness. Likewise, Father Natalio’s uncompromising Marxism is meant to be not so much the movie’s hope for the Catholic Church as its hope against it. Écrasez l’infame! just about sums it up, I think.

There is hardly any suspense surrounding the question of whether Father Amaro will do the right thing. The title gives the game away. Nor is there only one crime. Father Amaro is about as bad as a priest can be. Even though he still prays fervently and gives every appearance of sincerely believing in the religion he professes, this only makes him a bigger hypocrite, in Sr. Carrera’s view. The point of his film appears to be to offer us a progressive equivalent of one of those Victorian moral tales, like Eric, Or Little By Little by Frederic Farrar, the Dean of Canterbury, which were designed to mark out for us the primrose way to the everlasting bonfire. What a pity that their principled atheism means that neither he nor his film can have the consolation of looking forward to Padre Amaro’s eternal torments.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.