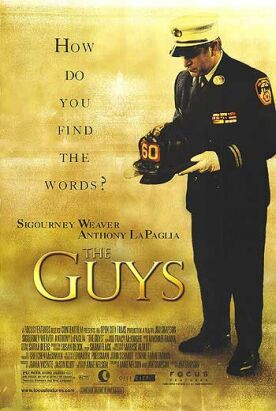

Guys, The

The film of Anne Nelson’s play, The Guys, directed by Jim Simpson, only accentuates its central and all-but fatal weakness, which is that it uses the ready-made emotions associated with the events of September 11, 2001 in a self-aggrandizing way. A writer called Joan (Sigourney Weaver) volunteers her services as ghost-writer for Fire Captain Nick Costello (Anthony LaPaglia), charged with the heavy task of delivering the eulogies for four of his men who died in the World Trade Center. He comes to her spacious apartment on the Upper West Side while the nanny is looking after the kids and answers her questions about the dead men. She then writes up the eulogies, which he approves.

Of course we can understand Joan’s wish to associate herself with the heroism of the New York City fire brigades, but in doing so she shifts the focus away from the hero-victims and onto herself, her career as a writer and a journalist (she’s been in some tough spots too, by golly) and even her good fortune in the New York property market. She got into the Upper West Side at the right time, you see, but she really likes Park Slope, where her younger sister lives, too. All this comes perilously close to trivializing the enormity of 9/11 and the reaction to it of all Americans as those horrible deaths are reduced to an excuse for Joan’s professional pride.

“When was the last time I heard anyone say they needed a writer?” she says exultantly about Captain Costello’s invitation to write his eulogies. What a good thing for her, then, that those men died! Of course she doesn’t say this, but her continual breathless interest in herself and her career is likely to suggest some such thought to the audience. “I want to do something, but this is all I know how to do: words,” she says at one point, as if her wish to “do something” is an emotional datum that is somehow on the same scale with the death of the firemen — or even with the feelings that all of us who did not actually lose a loved one in the disaster must share.

Similarly, there is something slightly sickening about the idea of her treating those feelings as owing something to her words, even if they do. The ghostwriter undoes her own work the moment she calls attention to herself as its author. So we see Joan weeping as she reads her own description of one of the men (is she weeping for him or for her own skill in eliciting the feeling?), which causes Nick to have to comfort her. She even imagines the two of them in a quasi-erotic situation, dancing, which compounds tastelessness with yet another vanity.

And then, at the climactic moment when we hear the fourth of the eulogies actually being delivered by Captain Nick — who is rather oddly wearing his fireman’s hat in church — her words about Fireman Barney, who was good at making tools, take on a new resonance: “When you’re answering an alarm, every tool counts,” the Captain says with a significant look at her. She too, it seems, can make a contribution. But wait a minute. Why are we supposed to be so interested in her desire to contribute when it is what she is supposedly contributing — the words commensurate with the heroism of “The Guys” — that is ostensibly the film’s subject?

Such a self-regarding — indeed narcissistic — approach to a national tragedy is all of a piece with the irrelevant voiceover intrusions from Joan’s ruminations on the meaning of 9/11, her own autobiography and the deeply silly moment when she stamps her little foot and says to God: “I want them back; I want them all back. That’s all I will settle for,” imagining as she does so the “tape” of the tragedy run backwards. There are brief moments in the film when it conveys a genuine feeling for the dead and the bereaved, but they are obscured by the framing device, which hints of a much greater interest in the feelings of Joan.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.