Honor Among Thieves (1)

The day after George Galloway, a Labor member of Parliament and prominent antiwar campaigner in Britain, was accused of having been in the pay of Saddam Hussein, the BBC announced that it was planning to run a dramatization of the “Cambridge spies” — Burgess, Maclean, Philby and Blunt — that would portray them in a “heroic” light. Jane Tranter, the BBC’s head of drama, was quoted in The Times of London as saying: “It would be a very bland drama which just said these men were heinous traitors and we hate them. We show their humanity and fallibility and the passions that drove them to betrayal and huge personal sacrifice.”

So far Mr. Galloway is denying the charges brought against him by the Daily Telegraph, despite captured Iraqi documents that show payments to the peace-loving socialist MP of more than a half-million dollars a year from the oil for food program. But if the evidence against him is as conclusive as it looks, he might want to take the hint offered by the BBC miniseries and be the first accused traitor to defend himself by asking: “What’s really so wrong with treason?”

Just listen to what Samuel West, the actor who plays the young Anthony Blunt, says about his character: “His treachery, if you can call it that, was leaking secrets to the Russians, who were our allies. Churchill wanted to keep them in the dark. If there is an organization fighting fascism in 1934 when there are hunger marches in Britain, of course you join it. Blunt’s actions did not harm people’s lives and he got out of spying when he could.”

In fact, Blunt himself admitted that at least one British agent was murdered as a result of the information he supplied to those Russian allies, but he was never prosecuted. And if he can be forgiven, why not Mr. Galloway, who hasn’t, so far as we know, got blood on his hands? Mr. West himself, according to the Times, “compared the spies’ communism to protests against the war in Iraq, saying that both were patriotic responses.” True, this patriotic response in Mr. Galloway’s case took the form of urging British troops during the war to disobey their orders and calling on Arab governments in the region to come to the aid of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. But no one paid him any heed. And, anyway, what about his rights of free speech?

Yes, Mr. West is just an actor, but let’s face it, there are a lot of people in America as well as Britain who might be persuaded by such a line of argument. The claim of intellectual, upper-class communists of 50 or 60 years ago, that they were serving a higher good than that of old-fashioned patriotism, is now available to everybody and hardly even requires belief in the higher good. It’s enough that the spies were victims, the poor dears, and made a “huge personal sacrifice.” The BBC miniseries is history for the Oprah generation.

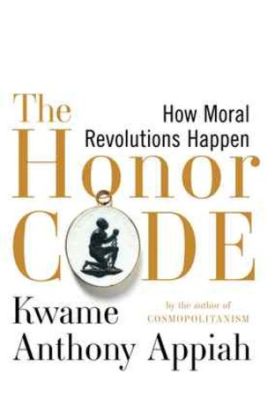

Not so long ago both countries could have taken for granted among their people a sense of honor and patriotism that was all but universal, but we now live in what Akbar S. Ahmed, a professor of international relations at American University, calls a “post-honor” society. Mr. Ahmed, a native Pakistani, uses the concept to distinguish ours from Islamic cultures in which honor is still a matter of life and death. In such a culture, as the Egyptian scholar Mansour Khalid once put it, “an Arab considers it an affront to his honor to suffer loss of face. This ‘tyranny of the face’ leads an Arab to do everything possible not to show his troubles to those close to him, let alone his enemies.”

We had a remarkable illustration of this principle during the war from Mohammed Saeed al-Sahhaf, the Iraqi information minister who went right on denying that there were any American troops in Baghdad even when they could be seen out the window. In the West, Mr. Sahhaf was quickly turned into a joke, but he was simply saying what he knew was expected of him as a man of honor. It wasn’t his fault if the façade that he had been called upon to prop up was transparent.

Saddam Hussein himself, who claimed in his interview with Dan Rather to have won the first Gulf War, was obviously of the same mind. Just look at the last Iraqi election, in which he won 100 per cent of the vote. If you’re going to rig an election in the West, you try to make it look real. But the aim of rigging the vote in an Arab country is not to produce verisimilitude but the most honorable result, construed as the most definitively positive one.

For the same reason, if it proves to be the case that, as some high administration officials in Washington believe, Saddam was killed on the opening night of the war, his brief and ambiguous public appearances after more than two weeks of silence as his army was collapsing could have been an elaborate “Weekend at Bernie’s” charade staged by loyal officers desperate to show that the regime would acknowledge no defeat.

I wonder, too, if Saddam’s failure to cooperate with the inspectors, which seemed to confirm those as yet undiscovered weapons of mass destruction, was a result of his fear of losing face. While the U.S. and the United Nations were insisting that Saddam give up such weapons, he couldn’t be seen to bow to their demands even if he hadn’t any or had so few as to pose no threat. If this seems improbable, consider that in the interview with Mr. Rather he denied he had any al-Samoud missiles, or that, if he had them, he would destroy them. Yet he did have them and was already on the point of destroying them.

In other words, he cared enough about his power and even his life to destroy the missiles — and maybe, for all we know, his weapons of mass destruction too. But he did not and could not care enough about these things to say that he was going to destroy the offensive items and thus do the bidding of his enemies. Had he done so, he would have shown weakness, and the foundation of honor and fear on which his rule depended would have been undermined.

We in the West could hardly wish for a return to Arab-style honor, but there ought to be something in between that and making excuses for those who betray friends and colleagues on account of their “humanity and fallibility” or the motives of high idealism on which they acted. Whatever happens to George Galloway, it now seems unlikely that he will ever feel even so much shame for his deeds as Anthony Blunt did when his treachery was exposed 23 years ago. I wonder if, along with the enlightened Western democracy that we intend to present to the Iraqis, we also mean to present them with the BBC’s enlightened attitude toward honor.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.