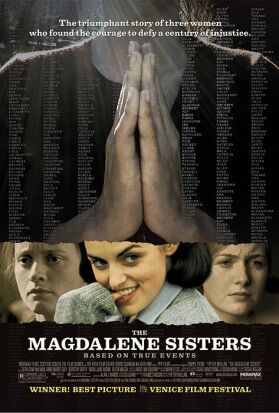

Magdalene Sisters, The

The movie business’s recent anti-Catholic phase, evident in such pictures as El Crimen del Padre Amaro or Costa-Gavras’s Amen, should be understood in the context of Hollywood’s former deference towards, even reverence for the Church. That may be why the latest exercise in Catholic-bashing, Peter Mullan’s Magdalene Sisters, prominently features a screening of The Bells of St. Mary’s and in particular Ingrid Bergman’s epiphany of faith, in a convent of Irish sisters who are systematically exploiting and mistreating a number of girls and young women.

Generally, these were “unwed mothers,” as they were known in the 1950s and 1960s when the film is set. Their sexual misbehavior was thought to have brought shame upon their families, who have sent them away in consequence. Mullan begins with the stories of three girls, only one of whom, Rose (Dorothy Duffy), actually got pregnant. Another, Margaret (Anne-Marie Duff) is raped by a cousin at a family wedding, though she gets the blame, while the third, Bernadette (Nora-Jane Noone), has merely ticked off the authorities by flirtatious behavior at the orphanage where she lives and is sent away to keep her out of trouble.

After these three girls’ stories are told in little vignettes at the beginning, we have the opening titles against a background of female names, inscribed as on a Vietnam Memorial-style wall, and furtive talk of an escape attempt by one of the girls — who is later brought back by her father, played in a scenery-chewing performance by Mullan himself. The imagery of war and prison prepare us for the scenes of hard labor as Rose, now renamed Patricia, Margaret and Bernadette join the other unfortunate girls in toiling at the commercial laundry run by the nuns.

All are equally subject to the iron discipline of Sister Bridget — played by Geraldine McEwan in a performance of great power and nuance that will do much to persuade weak-minded audiences that there is little to choose between nuns and storm-troopers — or, as Mullan was quoted as saying with spectacular disingenuousness when the film won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, “Taliban militants.” Yet her tyranny gives the other sisters no sense of fellow-feeling with the poor girls, who are locked up and beaten if they misbehave. Instead, they seem to enjoy bullying and torturing and humiliating them.

Let us stipulate that the Irish sense of sexual shame forty or fifty years ago was indeed unnaturally highly developed, and that places not unlike the convent of the Magdalene Sisters did indeed exist. Let us further stipulate that the Church was at fault for allowing them to exist, and to exploit the poor unfortunates who were given into their charge — often for trivial sins or no sins at all. Yet for all this, the scene of Ingrid Bergman’s cinematic transfiguration, praying to God to “remove all bitterness from my heart,” by throwing into contrast the sordid reality of the Magdalene Sisters, reminds us that they are not, cannot be the whole story.

For the ironies work both ways here, and with the best will in the world you couldn’t imagine that the bitterness has been removed from Mr Mullan’s heart. This fleeting and sardonically-intended imagery of piety, goodness and genuine religious devotion cannot help but raise the question in our minds: why do the movie-nuns in this case show none of these qualities? Mullan’s answer would seem to be that we were dupes for believing in them in the first place. His film plays upon the audience’s fear of being thought naVve about the potential for mischief and hypocrisy in the appearances of piety. You mean you don’t know what really went on behind those convent walls?

That’s why Mr Mullan, who was raised a Catholic but claims to have been a Marxist since the age of 15, has defended his film with reference to the women whom he claims to have talked to who have told him that being sent to the nuns was just like that — or actually worse than that. Here, folks, you may see the reality behind the appearance of holiness.

Well, yes. But it cannot be the only reality. A moment’s thought will persuade us that, however bad the nuns may have been, they could hardly have been so bad as this. For who may be supposed to take on herself the awesome burdens of a religious life only in order to exploit the slave labor of unwed mothers and other “bad” girls? Did they take those vows of poverty, chastity and obedience only in order to enjoy, so far as they could enjoy, the profits, such as they were, of a laundry? Was there among them not the faintest whiff of sanctity, nor a single soul to protest at the scandalous treatment of the girls?

To believe that there was not, you would have to be quite as naVve as someone who believed that such things as this film represents never happened at all. But the anti-religious sensibility in our time always tends to overstate its case — perhaps because at some level it must know what a powerful force for good it is trying to portray as unremittingly bad.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.