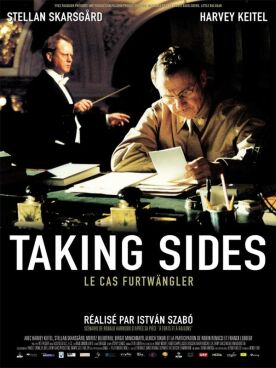

Taking Sides

Taking Sides is a disappointment. Directed by István Szabó (Sunshine) and adapted by Ronald Harwood from his own play, it deals with a subject of great potential interest: the examination, based on fact, by an American de-Nazification commission in post-war Berlin of the great German conductor, Wilhelm Furtwängler (Stellan SkarsgDrd). Furtwängler, though never himself a Nazi, was showered with honors by the Nazi régime and conducted the Berlin Philharmonic at a birthday celebration for Hitler. But he also helped Jews to escape from Germany and was doubtless to a considerable extent a victim of the fact that he was Hitler’s favorite conductor — and did not openly repudiate him.

The great problem with the film is the character of Major Steve Arnold (Harvey Keitel), who is charged with the task of examining Furtwängler and whose growing obsession with finding him guilty remains a mystery. Obviously going beyond a disinterested search for the truth, or even a passion for justice, his vendetta against the great man may be motivated by jealousy of his stature and the awe and respect in which he is still held, even by many Jews, or it may be something even darker and more disreputable. But it is hard to imagine what hidden motive could be so lacerating as to drive Major Steve to condemn Furtwängler, as he does, simply for avoiding the hangman.

What it cannot be, I think, is an attempt to please his superiors, one of whom, General Wallace (R. Lee Ermey) tells him: “Find Furtwängler guilty; he represents everything that was rotten in Germany.” Ermey is of course best known for roles like that of the unsympathetic Marine drill instructor in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket and thus is presumably on board as part of a half-hearted attempt to shift the blame (if blame it is) for Furtwängler’s persecution onto the broad shoulders of the U.S. Army and, by extension, its excessive discipline and black-and-white views of loyalty. But even if you subscribe to this, the official Hollywood view of the U.S. armed services, you won’t buy the simple-minded general as the primum mobile of all that is to follow.

My guess is that Harwood and Szabó were so caught up in the task of selling their standard liberal message — we-are-all-guilty, not-black-and-white-but-grey — that they forgot all about the more basic artistic task of motivating their principal character. Major Steve, supposedly a shrewd insurance investigator, is so dumb that he can’t even see the connection between the relative compassion of his Russian colleague, Colonel Dymshitz (Oleg Tabakov), and the latter’s own fear of getting on the wrong side of a totalitarian régime. Nor does the light ever dawn when the major taunts Furtwängler with his dislike of the younger, more glamorous (and more Nazi) Herbert von Karajan as “the aging Romeo, jealous of the young buck” — even though he, Major Steve, has himself been beaten to the punch with his pretty secretary, Emmi Straube (Birgit Minichmayr), by his youthful assistant, Lt. Wills (Moritz Bleibtreu).

If you can get over the rather serious deficiency of its having such a block-headed hero, the film does offer some things to like — to start with, the music, though there is not nearly enough of it. Lt. Wills, a Jewish refugee now serving as a translator with the U.S. Army, is a bit of a stick whose only real function is to show that a Jew can forgive where Major Steve cannot, but the immense dignity brought low — by guilt as well as by persecution — of SkarsgDrd’s Furtwängler is well worth watching. So is Miss Minichmayr’s Emmi, the daughter of one of the German officers who was executed for his part in the plot against Hitler of July, 1944. Celebrated as the daughter of a hero after the war and a spell in a concentration camp, she is driven by sympathy for Furtwängler to admit that even her father only acted when it became clear that Germany would lose the war.

I also liked Ulrich Tukur’s portrayal of Helmut Rode, a 2nd violinist with the Berlin Philharmonic whose feigned innocence, real guilt, vindictiveness against Furtwängler and pathetic need to curry favor with power make him a sort of German Everyman. Interesting in himself, he is also an emblematic figure standing for all those without whom tyranny could not exist. This character’s presence here is designed, I take it, to show the absurdity of the Major’s persecution of Furtwängler, who comes across as a man of integrity by comparison. But this only reinforces one’s sense that the whole scenario has been rigged for the great conductor to win. How much better — and more dramatic — if he could have done so against a more credible adversary than the self-righteous, thick-witted Major Steve.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.