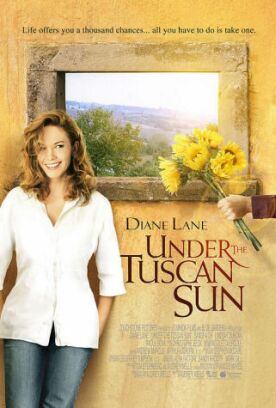

Under the Tuscan Sun

Under the Tuscan Sun may just be the most vulgar, tasteless, soppy, wish-fulfilling chick-flick since The Divine Secrets of the Ya Ya Sisterhood. Or even How Stella Got Her Groove Back. Maybe even since the grandmammy of them all of more than a decade ago, Fried Green Tomatoes. Based on the popular memoir by Frances Mayes and adapted and directed by Audrey Wells, it tells the story of Frances (Diane Lane) whose rat of a husband not only divorces her but uses his new girlfriend’s money to buy her out of her own house. Persuaded by her lesbian friend Patti (Sandra Oh), who has just become pregnant, to take her ticket to go on a “Gay Away” trip to Tuscany, she decides on impulse to buy a Tuscan villa and settle there.

Miss Wells doesn’t have her say so, but Frances, now called Francesca by the lovable Italians, may be thinking that the odds of finding another man are better in Tuscany than in San Francisco. At any rate, she does find one there, the dreamy Marcello (Raoul Bova), who takes his place alongside Viggo Mortensen (A Walk on the Moon) and Olivier Martinez (Unfaithful) as younger men to whom the movies have assigned the enviable task of awakening to furious erotic life and energy the delectable Miss Lane and so driving home the point that, as she puts it, “You can’t help feeling that these Italians know more about having fun than we do.”

This is a variation on a very old theme in describing Americans in Europe and why Thomas Appleton is supposed to have said that “When Good Americans die they go to Paris.” Something like it is the theme of Henry James’s novel The Ambassadors — which may be more to the detriment of James than it is to the benefit of Audrey Wells — and it is the subtext of all that Hemingway-Fitzgerald-Henry Miller expat lit of the 1920s and 1930s. I think especially of the corrupt union leader in John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy who was forever maundering on about the French understanding of “the art of living.” Most recently we’ve had another updated version of the theme in Le Divorce. But perhaps this post-Iraq War removal of the art of living from Paris to Tuscany will prove more popular.

The older version of the myth was a male fantasy of female sexual availability, so it is only appropriate that the newer should be a female fantasy of female sexual availability. Turnabout is fair play. Francesca certainly seems to enjoy the art of living with Marcello and squeals with girlish delight and kicks her little legs to think that she’s “still got it” — “it” being, apparently, the ability to induce a man to sleep with her for pure sexual enjoyment and then abandon her. I hope no one tells her how many other women still have as much of “it” as this — and wish, perhaps, that they had either less or more of it. No regrets for Francesca, however. Neither she nor her new best friend, the less-than delightfully Bohemian Katherine (Lindsay Duncan), nor Katherine’s mentor, the late film director Federico Fellini, have any patience with regret. Federico told Katherine that she should never lose her childish innocence and enthusiasm and she has so far heeded his advice as to have regressed to a nearly infantile state.

As such she becomes part of Francesca’s surrogate family — which also includes Patti the lesbian, Patti’s new baby, Signor Martini (Vincent Riotta), her kindly lawyer and man of business, the Polish workmen at her villa, a young couple (Pawel Szadja and Giulia Steigerwalt) whom she has brought together and any passer-by who happens to strike her fancy, especially if he is young and handsome and can claim to be a fan of her writing. This gay-inspired trope of the factitious family — family as friends and lovers instead father and mother and relatives — is a common one in Hollywood, but is, I suspect, less popular in the real, non-cinematic Italy. As with the art of living, however, this theme was made to order for the Hollywood dream factory, whose job it is to conjure up the great good place where fantasies can come true. Still, it would aid believability if the fantasies could be limited to one per movie.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.