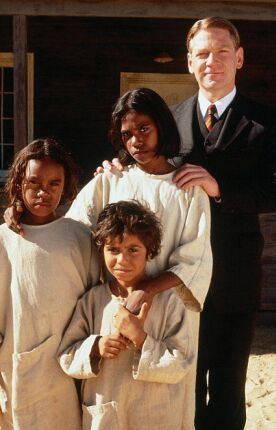

In America

In America by Jim Sheridan, director of My Left Foot and In the Name of the Father, is, among other things, a rather affecting story of a poor immigrant family from Ireland coming to terms with its grief over the loss of a son to cancer. I found it very watchable, at least up until the dreadful ending, mainly on account of tremendous performances by the principal actors, especially Paddy Considine as Johnny Sullivan, an out-of-work actor, Samantha Morton as Sarah, his wife and Sarah and Emma Bolger who play their two little girls, Christy and Ariel. Sure it’s kind of hokey, and it gets hokier as it goes along until the advent of the hokissimus E.T. But it’s (mostly) hokey in the good way that Hollywood used to be hokey, not the bad way that it (mostly) is now.

Movies like this which are designed as as a species of grief-counseling have a long and honorable history, and we naturally love to see people coming through and coping with such a terrible bereavement. But wait just a minute. Keep your eye on that title. What has America got to do with grief over the young son, Frankie, that died? Why are the family immigrants? Why have they brought their sorrows to America? And why is Johnny connected with the thespian’s trade rather than that of agricultural worker or some other that looks more, well, immigrantish. I think the answers to these questions are connected. Evelyn Waugh once wrote of “the Irishman’s deep-rooted belief that there are only two final realities — Hell and the USA,” and Sheridan’s film could be seen as a kind of gloss on this idea, since in it America is a kind of stand-in for Heaven: the land of make-believe, the place you can still believe in when you can’t believe in anything else.

At times this idea is reinforced by heavy-handed symbolism, as in the fact that the ice-cream parlor where Sarah works and the kids spend their happiest hours is called “Heaven.” The family’s Catholic faith has been shaken to its foundations by the death of Frankie and looks like being shaken again when Sarah gets pregnant and is told of the probabilities that either her life or the baby’s, or both, are threatened if she takes the child to term. Meanwhile, Dad can’t pay the bills because he can’t get work as an actor because he can’t feel anymore — do you begin to feel the encroaching hokiness?. The danger to his wife helps to teach him to make believe again, at her urging, for the sake of the kids and so to find work at last, but he remains emotionally paralyzed and angry at God.

This is where E.T. comes in. A frightening but really kindly neighbor, Mateo (Djimon Hounsou) an African artist who describes himself as an alien, like E.T., is also dying — of AIDS. Oh dear. Hokier, still. Assuming the now familiar Hollywood role of Wise Black Counselor to the family, Mateo manages before popping his clogs to teach each of them something about the acceptance of death and the consolations of the afterlife. This appears to be something like Disneyland, and its realization in Spielbergian terms as the alien African AIDS sufferer goes “home” to be with Frankie and E.T. can only be an affectionately patronizing European joke about America as the land of fantasy and fairy tales.

The film is saved from being merely offensive, however, not only by the performances but also by being told largely from the point of view of the child, Christy, whose voiceover as she narrates for us her video diary is not so annoying as you might expect. For her it is entirely natural to see America as a kind of fairy-land. Accordingly, she imagines she has been granted three wishes, which she uses to make the consolations of America acceptable to her parents as a replacement for the consolations of religion, which they have lost. That America itself and its world-beating popular culture are a kind of religion, it seems perfectly natural for these attractive Irish folk to assume, but it leaves a bad taste in the mouth of this American, who has not yet entirely given up the hope of more traditional consolations.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.